- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The secrets of Ethel

- Article Subtitle: Reimagining the catalyst of the literary hoax

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Ern Malley’ – a great literary creation and the occasion of a famous literary hoax – has continued to attract fascinated attention ever since he burst upon the Australian poetry scene more than seventy years ago. But his sister Ethel has attracted little notice, she who set off the whole saga by writing to Max Harris, the young editor of Angry Penguins, asking whether the poems left by her late brother were any good, and signing herself ‘sincerely, Ethel Malley’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sincerely, Ethel Malley

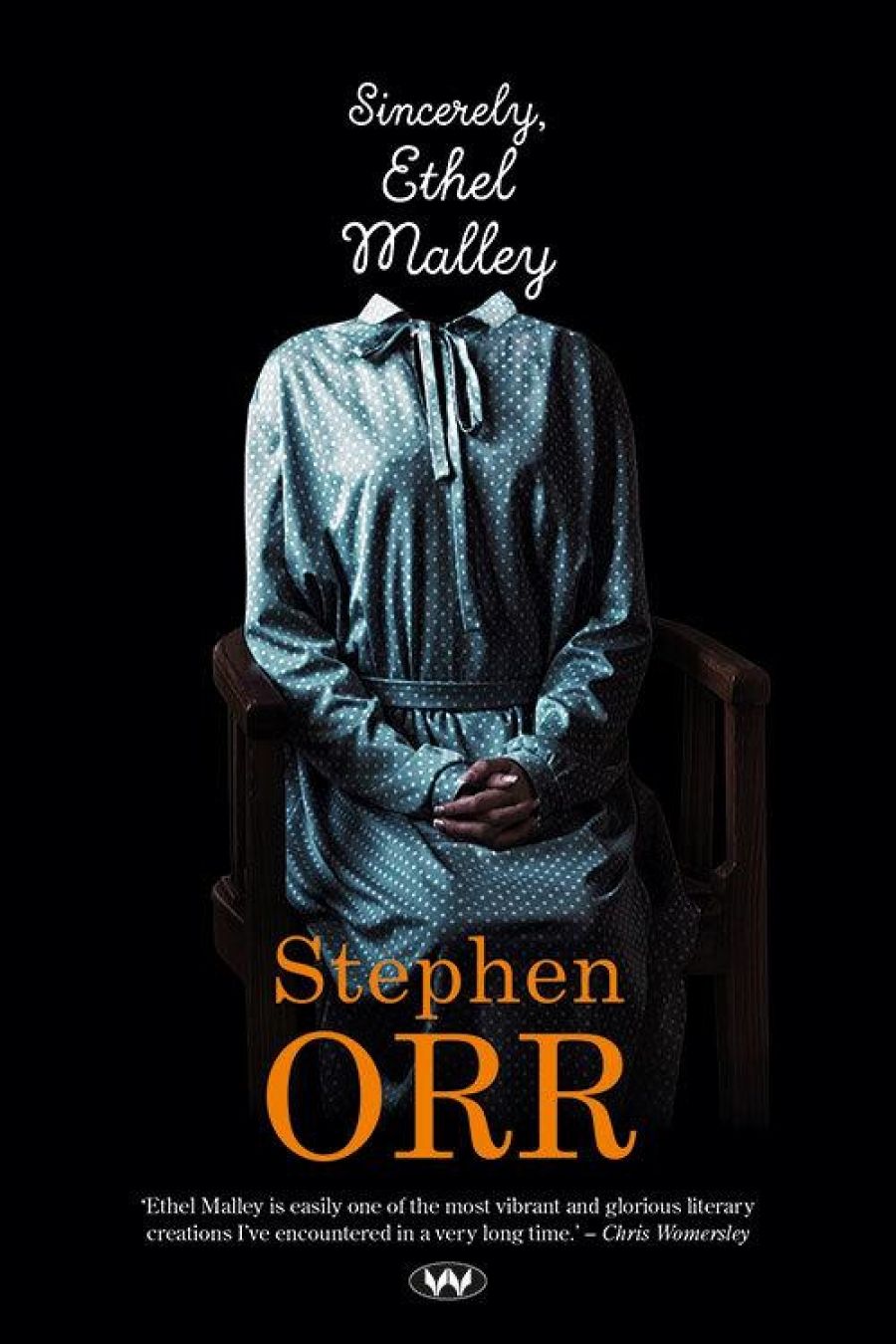

- Book 1 Title: Sincerely, Ethel Malley

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $34.95 pb, 441 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/GjDYbm

In his new novel, Stephen Orr gives her a voice, a bodily presence, thoughts and passions and secrets of her own. No longer merely instrumental, here she moves the story along, with her letters to Harris, her travels to Adelaide and Melbourne, her strong reactions to people and events. Ethel is the narrating consciousness, and her narrative works by accumulation, piling up hints and guesses about Ethel and her brother, within a structure provided by the well-known historical events of the Angry Penguins publishing hoax and the subsequent court case where Harris was convicted of publishing ‘indecent advertisements’.

There is much, dear reader, that I cannot reveal for fear of spoiling the structure of suspense so cunningly woven throughout this novel. I think I can mention, though, one trail of clues I particularly enjoyed: Ethel’s stories about the work her brother and father did in his shed, putting together bits and pieces of objects that Ern had found while beachcombing to make sculptures. This is clearly a work of collage, even bricolage, which has parallels with the poems, which were made up of random phrases, misquotations, and false allusions (as the hoaxers, James McAuley and Harold Stewart, claimed). The vexed question of Ern Malley’s apprenticeship in his art is surely addressed here?

Sincerely, Ethel Malley does not provide a definitive answer to that major question: who created the poems? Ethel’s narrative, in its final moments, offers what looks like the answer, one that is bound up in a chapter of Ern’s biography that has been eclipsed from history, about a love that dare not speak its name. But then the novel’s final chapter reveals the discovery of Ethel’s manuscript of the story we have been reading, found after her death – a manuscript which shows that ‘Eth was talented. She could write. Which means perhaps that she could’ve written the poems, but we’ll never know, will we, dear reader?’ The speaker here, who has launched Ethel’s story into the world (just as he once launched Ern’s poems), is of course none other than Max Harris himself.

Indeed, the Acknowledgments also claim to be authored by Max, thanking real people in the present day as well as ‘the dozens, the hundreds who have written about Ern over the years – painted him (starting with Sid Nolan), set him to music, analysed him’. Perhaps this is the final irony, that Ern still prevails despite the possibility that it was really Ethel all along. Maybe they were one and the same person? I thought of that great literary portrait of a multi-gendered soul, Eudoxia/Eddie/Eadith in Patrick White’s The Twyborn Affair.

Orr’s novel brings alive Max Harris as well as Ethel Malley. Ethel’s narrative makes Max a vividly realised character, a bright young man pulled in several directions by his modernist mentors John Reed and Sidney Nolan, his teacher Brian Elliott, his girlfriend (and future wife) Von, and his ally, the bossy Mary Martin – and by Ethel herself. At the same time, it projects Ethel the teller as a passionate and troubled young woman, quick to fly into a rage if her late brother Ern is criticised or her accounts of the past are queried, and all the while harbouring a strong sensual attraction to ‘Maxie’.

Ethel has been a real presence to other writers. Max Harris himself confessed to liking her ‘no end’, seeing her as ‘a finely conceived Jane Austen character’. In The Ern Malley Affair (1993), Michael Heyward wrote, ‘If Ern Malley’s work aspires to the condition of poetry, Ethel’s letters aspire to fiction’; in the process of demonstrating her epistolary art, he sketches an engaging portrait of the woman suggested by her words.

Now we have Stephen Orr’s Ethel. She is, like Ern’s poetry, something of a collage herself. She moves between registers, from the 1940s suburban idiom that is her Croydon inheritance to a range of high-culture references, like ‘reading poets from Dante to Eliot’, playing classics on the piano and taking over the direction of Max’s student production of James Joyce’s Exiles. Max, in a moment of anger, accuses her of sounding ‘arcane, like someone’s writing your lines for you’. She retorts, ‘Well, maybe they are. God perhaps.’ This bricolage is complicated by a degree of gender dysphoria that seems to afflict Ethel. She refers, for example, to her ‘Ethel bits. My bosoms, like a dromedary in my twenty-ninth year [misquoting Ern’s most ridiculed lines, ‘In the twenty-fifth year of my age / I find myself to be a dromedary’] … And lower, down, into what might’ve belonged to an old woman, although I wasn’t. Secret from all except Ern …’

Ethel’s narrative shows her to be familiar with many instances of fakes and forgeries, which she deems a form of ‘intellectual masturbation’. She challenges the South Australian Museum for presenting as authentic a skull which she knows from her reading to be a fake, and when her advice is ignored she steals it. Her story about how their father Bob Malley died in the desert, competing in the ‘Esso Reliability Trial’, is one of her less successful attempts to elaborate the Malley legend – but it does bring to mind Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake and his more recent novel about the Redex trials, A Long Way from Home.

Ethel’s story is an echo chamber, like the whole collection of Malley works. David Brooks questioned the hoaxers themselves in his ‘secret history of Australian poetry’, The Sons of Clovis (2011). Now Stephen Orr’s Sincerely, Ethel Malley suggests another level of hoaxing altogether.

Comments powered by CComment