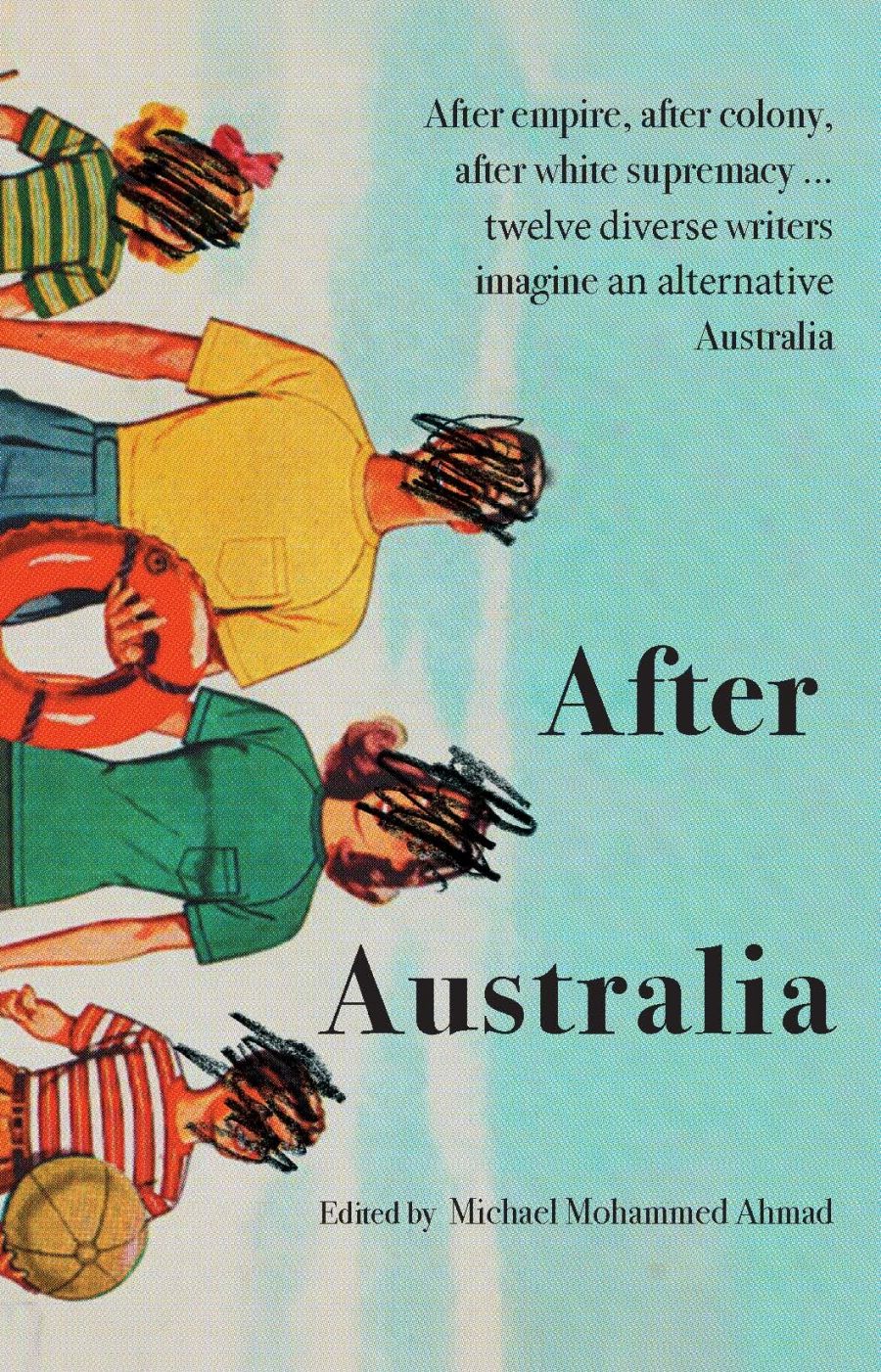

Acknowledging the limits of Acknowledgments of Country, the Wiradjuri artist Jazz Money once wrote:

whitefellas try to acknowledge things

but they do it wrong

they say

before we begin I’d like to pay my respects

not understanding

that there isn’t a time before it begins

it has all already begun

The sentiment is salutary for an anthology like After Australia, in which several writers – through ecopoetics, speculative fiction, memoir, and other modes – imagine what has begun, or is yet to begin, amid the cruelties and joys of our history.

Recalling Kim Scott’s haunted approach to questions of conciliation in Taboo (2017), Karen Wyld traces the lines of a family tree backward through time, uncovering blood on the leaves and blood at the root. As one character remarks: ‘Where had all the Aboriginal people gone?’ It’s a question that has nagged at some of our most acclaimed authors. Think of David Malouf’s novel Remembering Babylon (1993): the evidence afforded by its 200 pages might suggest that, on occasion, even Malouf’s memory failed him (not a single Aboriginal voice punctuates its pages). Similar critiques have been made of books like Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet, in which the biggest guest at the house of the Lambs and Pickles is the absence of any living Aboriginal voice from the narrative. As academic and poet Jeanine Leane has written, this issue afflicts much of Australian literature. Similar to her other work, Wyld draws our attention here to the way Aboriginal lives are written out of history, erased from our collective memory.

Recalling Benedict Anderson, that seminal cartographer of empire and the role of communication technologies in manufacturing ‘imagined communities’, Roanna Gonsalves writes poignantly about the force with which concepts take on material life, impacting the world like a weapon:

With charcoal, gum, and shark oil, as the printer worked the inkballs to distribute ink evenly across worn metal type, a colony was carved from a continent. The Sydney Gazette spread the stories of this colony across the world, through sail and through whisper, through a process of accretion and embellishment, through a process of shaping and sculpting according to the needs of those who controlled the purse. Shammy understood the power of this alchemy. She gripped the frame of the press tightly, felt the strength of the tree from which it had been cut.

It is impossible to read something like this without acknowledging that to read and write history – even speculative or alternative history – is to engage with first principles; that history’s importance lies not only in who writes it, who tells it, but how it is listened to and understood.

A similar sense of alchemy pervades Michelle Law’s ‘Bu Liao Qing’ (the title recalls Eileen Chang’s 1947 screenplay as well as Hong Kong director Doe Ching’s 1961 film and its eponymous song). Law’s narrative reads less like dystopian speculation than as a weary mapping of real possibilities, alive with spooked unease. As in Lin Dai’s song, the raw aftertaste of loss and yearning is palpable (at one point a mouldy ceiling collapses on a student’s head, evoking the trauma of school building collapses in Sichuan in 2008). Law’s narrative reminds us how traumas often do not manifest until, with perilous precision, they interrupt our waking lives, like Georges Perec’s train in L’Infra-ordinaire:

What speaks to us, seemingly, is always the big event, the untoward, the extra-ordinary: the front-page splash, the banner headlines. Railway trains only begin to exist when they are derailed, and the more passengers that are killed, the more the trains exist.

Ultimately, Law seems to suggest, some departures never end: the finality of departure yields only to the haunting of memory, the constant slow-motion replay of loss.

Harnessing the mad energy that characterises his best work, Omar Sakr’s ‘White Flu’ is an eerily, furiously talented pastiche, and a prescient one (Virus falls upon the country! Waves of panic contort the town! No one is safe!). With satirical élan, Sakr interrogates the intersections of xenophobia and pandemic fear, reminding us that the anonymity afforded to whiteness, its furtive, blank neutrality, can be a curse as much as a blessing:

It quickly became apparent that [the virus] was devastating the West in particular, and people of European or Anglo descent seemed to be the only ones dying. Ancestry dot com crashed and kept crashing from the demand: everyone suddenly wanted to know where they came from.

At its heart, ‘White Flu’ is about repression: sexual, political, cultural, and psychological. Like Martin Amis or Philip Roth (or, locally, Michael Mohammed Ahmad or Ouyang Yu), Sakr displays a Rabelaisian fondness for the elaborate, carnal grotesqueries of bigotry and the taboo: newsreaders uncritically recite the grievances of white supremacists; the narrator’s anti-Semitic brother plays both devil’s advocate and accomplice; and the deep-sweat insecurities of masculinity and sexual longing are related with anxious, propulsive candour.

Familial and cultural angst are also at the heart of Sarah Ross’s contribution, where the author, seeing herself reflected for the first time on the cover of a book, realises that there exists ‘another place or another world where people looked like me’. Yet insights can carry pain: on Father’s Day and at parent–teacher meetings, she experiences the cold lateral exclusion of being caught between wanting to fit in and not wanting to upset her mothers. Hearing the strictures of Pope John Paul II against same-sex unions, she remarks: ‘We listened to it in the same way you hear white noise in the background, it wasn’t turned down or censored, it was just a backdrop to the world we lived in.’ This is white noise as backdrop, as necessary conditioning: the dull awakening to an environment that does not provide an equal measure of safety and comfort to all. In this world, life can feel like a hostile force, doling out its comforts as partial and attenuated as any ordinary quantum of prejudice can allow.

A subtly threatening quality characterises Khalid Warsame’s writing. ‘List of Known Remedies’ is a somewhat perambulatory narrative – detached, quietly aloof – but is animated by the author’s sense of being haunted, not so much by memory or human attachment as by the possibility of their loss. The writing is rich with implication (if not incident) and carries an understated, David Byrne-esque flair for the anthropological detail of human anomie and urban disrepair.

Hannah Donnelly intervenes throughout the collection, showing the reader around, guiding you through the exhibits, drawing our attention to both the humour and unflagging violence of our shared histories. Making connections between Pemulwuy and the horrors of government bureaucracy, childhood bike accidents and the eugenics of A.O. Neville, Donnelly’s anecdotes are an accumulating gallery of revelations: impassioned, vibrant, and enlivened by graceful humour.

Like the oral transmission of knowledge, the work of history, even speculative history, is one of constant returning – a gradual uncovering. The veil lifts; the layers of atomisation and confusion that keep us from seeing the connections that were always there disappear. An ear attuned to what is being said – along with the power to listen – is what this anthology offers, allowing us to parse through the white noise, until one day we are ready to acknowledge the frequencies underneath.