- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The dual crises of the recent bushfires and the Covid-19 pandemic have exposed structural weakness in Australia’s economy. Our export income is dominated by a few commodities, with coal and gas near the top, the production of which employs relatively few people (only around 1.9 per cent of the workforce is employed in mining). The unprecedented fires, exacerbated by a warming climate, were a visceral demonstration that fossil fuels have no role in an environmentally and socially secure future. Global investors are abandoning coal and, in some cases, Australia. Meanwhile, industries that generate many jobs – education, tourism, hospitality, arts, and entertainment – have been hit hard by efforts to reduce the spread of the virus.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

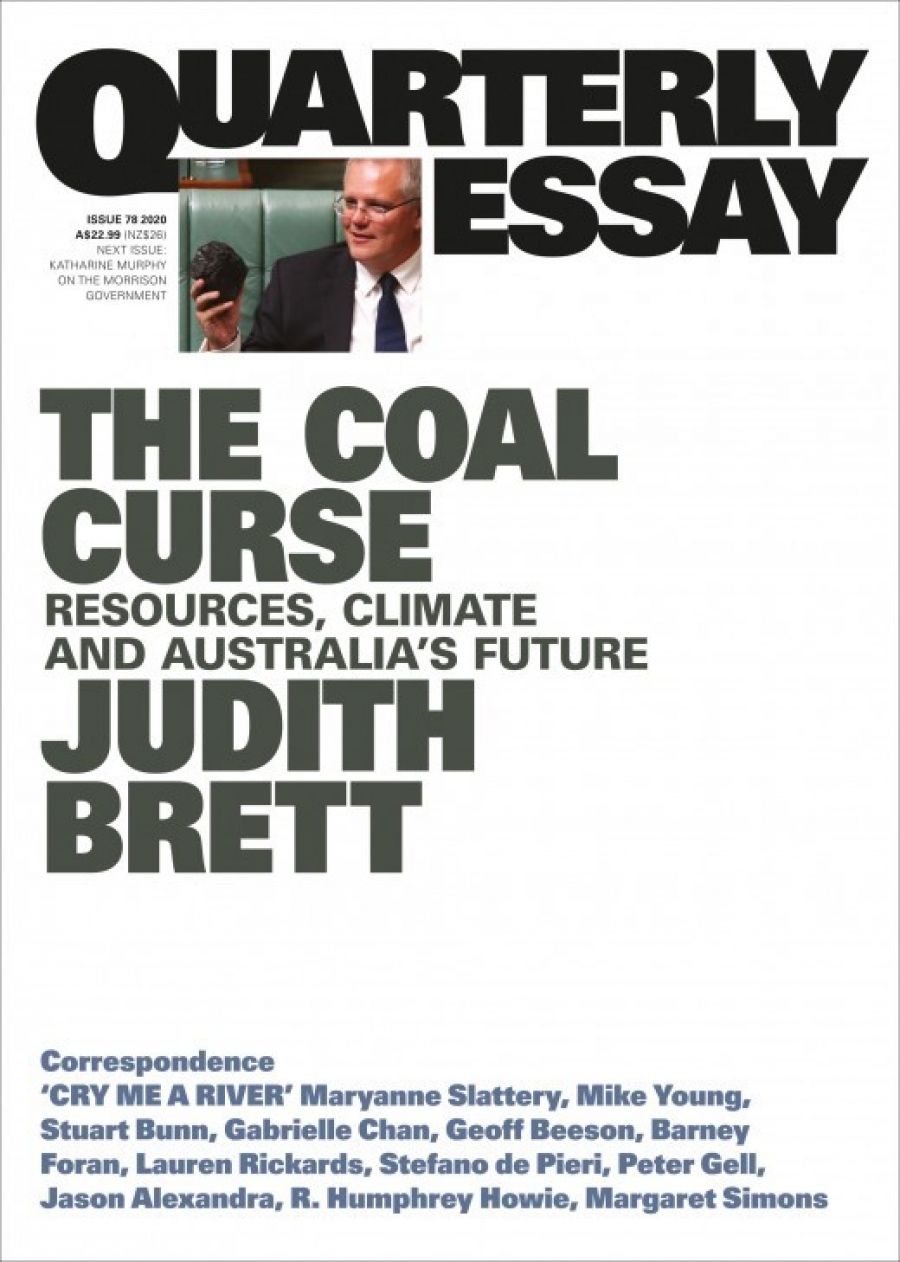

- Book 1 Title: The Coal Curse

- Book 1 Subtitle: Resources, climate and Australia’s future (Quarterly Essay 78)

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $22.99 pb, 136 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/o1EGn

Yet the Coalition appears inextricably yoked to the interests of the fossil-fuel industry. This is the situation that Judith Brett, in her new Quarterly Essay, lays before us as she investigates the federal government’s perilous and baffling obsession with coal. An erudite public intellectual and crisp writer who has spent more time than most examining the liberal tradition, Brett opens her essay by taking us back to the pre-pandemic summer of 2019–20, when coastal residents were huddling on the beaches under orange skies as fire fronts engulfed swaths of south-eastern Australia. Our prime minister had taken flight to Hawaii on the pretence that these conflagrations were part of a regular cycle. On his return, people wanted Scott Morrison to talk about climate change, they wanted decisive action and leadership, not a ‘hug from Scotty’, writes Brett. Like many of us, Brett was deeply affected by the fires. Her cherished family campground, with its ‘magnificent old mahogany gums’, was burned. She didn’t face the ‘horror of the walls of flame’ but mourns the loss of countless wildlife. With admirable candour, Brett confides that her essay is motivated by grief and anger.

The fires intensified scrutiny of Australia’s position on climate, drawing international attention. Brett reminds us that Australia was once a ‘middle-ranking power that could punch above its weight’. Now its reputation is shredded.

Global investors are abandoning coal and, in some cases, Australia.

How did this situation arise? To understand it, says Brett, we must go back to the foundations of the colonial economy, and ‘like so much else in our history, the story begins with wool’. The grazing of sheep over millions of acres of Aboriginal land made Australia a wealthy nation and established the dual structure of the economy we have today: an ‘export sector employing few people and a domestic sector where most people work’. Wool exports peaked in the 1950s, but just as demand began to plummet, international demand for our minerals rose. We traded one type of raw export commodity for another in iron ore and bauxite, transforming the north and west of Australia to the detriment of Aboriginal people. Successive governments failed to stimulate a skilled and innovative export manufacturing sector. By the 2000s, the coal rush had begun, generating enough export income to allow the Howard government to ignore further long-term economic reform and to indulge in ‘attacking identity politics, fighting the history wars and distributing largesse to retirees and middle-class taxpayers’. The disadvantages are that we are hooked into a declining sector of world trade, the price of commodities relative to manufacturing is falling, and we are more vulnerable to price volatility. This is the resource ‘curse’ of the essay’s title, the paradox that nations rich with non-renewable natural resources tend to have poor development and less democracy. Developing nations such as Nigeria and Venezuela fall into this category. Theoretically, Australia’s strong civil institutions should protect it from the worst outcomes, such as corruption.

The economic history that Brett provides is a partial explanation that relegates the environment to the background of human affairs In a short counterfactual, Brett contends that if climate change hadn’t intruded, the story of Australia’s economic development could have continued with relatively little debate or turmoil. Human activities affect more than the atmosphere. Habitat destruction, deforestation, soil erosion, depletion of freshwater, chemical pollutants, and more, mark Australia’s relationship with its environment, and this has contributed to the global species collapse that some scientists term the sixth mass extinction. The separation of environment from economy could never have been sustained, and this conceptual split is in part the cause of our current predicament.

The second half of the essay is compelling and persuasive as Brett, with careful rigour, demonstrates how our politics was captured by the fossil fuel industry, beginning with mining lobbyists who hired conservative speechwriters in the 1970s, developed PR expertise and circles of influence, won the battle over Aboriginal land rights, drew on the US model of denigrating public trust in science, and sank the emissions trading scheme and super profits tax by convincing the Australian public that its very prosperity was underpinned by mining. Decades of cultivation of a network of climate deniers ‘paid off in spades’ when Tony Abbott became prime minister in 2013, observes Brett.

Judith Brett (photograph supplied)

Judith Brett (photograph supplied)

Fossil-fuel interests converged with identity politics for those who feared the loss of a ‘masculine-dominated industrial modernity in which they had enjoyed power and success’. Brett explains this is why the attachment to coal goes beyond reason: it is fused with ‘culture wars’ that are based on personal identity and conflicting world views. The National Party’s Bridget McKenzie has stated that coal is a ‘religion’ for some in the party. As Brett reveals, it’s more than just a few politicians who push this agenda: there is a cohort of business leaders, lobbyists, and bureaucrats who move across these domains of influence, supporting one another and sharing similar views. On their own, many of these observations aren’t new, but the persuasive power of Brett’s essay lies in her accumulation and piecing together of so much evidence.

At the conclusion of the essay, Brett attempts to end with some hope, asking whether the disruption of the pandemic might be an opportunity to refocus the economy, to take steps towards creating a highly skilled, innovative manufacturing sector based on renewables. However, even an option that barely challenges the status quo seems unlikely, such is the dominance of coal. Brett admits the signs are that it will be more ‘business as usual’. The National COVID-19 Coordination Commission, for example, is stacked with people who have links to fossil fuel.

Judith Brett’s essay makes grim but thoughtful reading. It’s useful to know where the problems lie and what needs to change for those who, like Brett, care about preventing what she calls the ‘catastrophic fires and heatwaves the scientists predict, the species extinction and the famines’.

Comments powered by CComment