- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

No Australian feminist is likely to forget the moment when Germaine Greer appeared on Q&A and declared that our first female prime minister should wear different jackets to hide her ‘big arse’. Greer, of course, has blotted her copybook many times before and since, but if we needed proof that a woman leader could not catch a break in this country, here was Australia’s most celebrated feminist joining in the new national pastime of hurling sexist invective at the prime minister.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

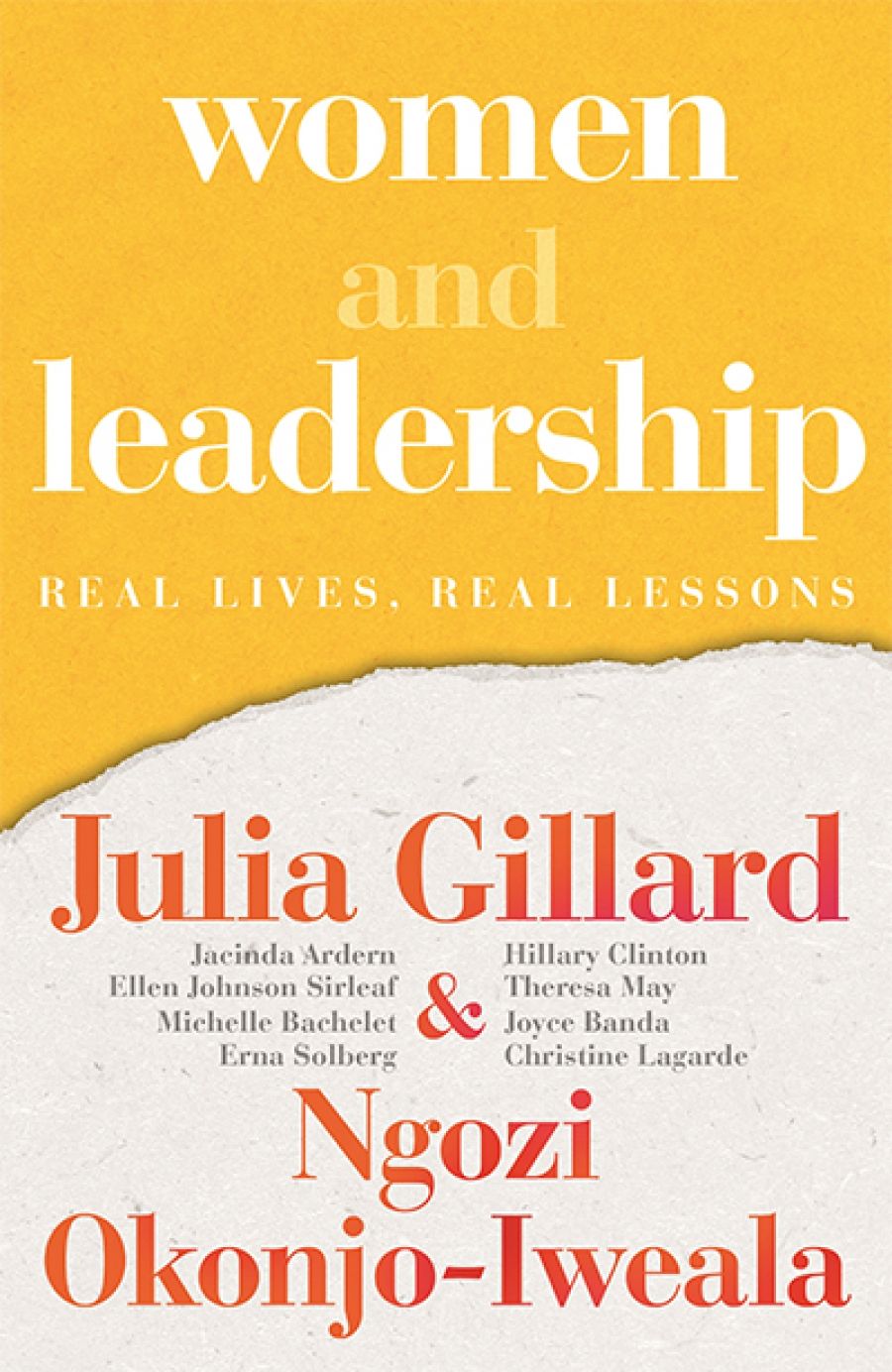

- Book 1 Title: Women and Leadership

- Book 1 Subtitle: Real lives, real lessons

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $34.99 pb, 326 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qJY7b

This nadir of Australian discourse on women’s leadership takes on a new light when considered by Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, two-time Nigerian finance minister and Julia Gillard’s co-author of Women and Leadership: Real lives, real lessons. ‘How ridiculous,’ says Okonjo-Iweala. In Africa, she points out, ‘Julia would be seen as skinny’. It’s a witty moment in what is otherwise a turgid treatment of the slippery topic of ‘women’s leadership’, which Gillard is currently investigating via a dedicated global institute at King’s College, London. Okonjo-Iweala and Gillard compare their divergent experiences in politics with those of eight prominent women politicians from around the world: former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, former UK prime minister Theresa May, former president of Chile Michelle Bachelet, former Malawian president Joyce Banda, European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde, Nobel Prize-winner and former Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg. And of course there is Jacinda Ardern, whose steady handling of the coronavirus crisis in New Zealand and compassionate response to the Christchurch massacre have inspired thousands of articles about the value of ‘empathetic leadership’ – often coded explicitly as female.

Thankfully, Gillard and Okonjo-Iweala warn against the dangers of ‘requiring women leaders to pick up the burden of always being the nicer person’. They note that research shows that, rather than rewarding empathy in women leaders, we expect it and ‘mark them down in our regard if they do not exhibit it’.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (photograph via Penguin Random House) and Julia Gillard (photograph by Peter Brew-Bevan)

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (photograph via Penguin Random House) and Julia Gillard (photograph by Peter Brew-Bevan)

The authors draw on research throughout the book to explain how people perceive women leaders, from the obsession with their looks evident in Greer’s comments, to the propensity to think of them as ‘a bit of a bitch’. These evidence-based insights run alongside individual testimonies from their interviewees, clubbily dubbed ‘our women leaders’.

It’s the interviews with the diverse roster of politicians that provide the real highlights of this book. We hear of Johnson Sirleaf’s lifelong battle to serve her country, encompassing jail, exile, and the difficult decision to leave her children at home while she pursued an education in the United States. Equally impressive is Bachelet, who was tortured by the Pinochet regime in the 1970s but went on to become president of Chile twice. She is now the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Most striking is the revelation that two of the women – Sirleaf and Banda – had to leave abusive marriages on their way to becoming the first female leaders of their countries. Not even the most powerful women are free from male violence. For her troubles, Banda was described as a cow who should have been ‘kept at home for milk’.

If Gillard and Clinton come across as particularly battle-scarred from their treatment by the media and their political opponents for the sin of being women who sought power, Ardern and Solberg seem to come from a different planet altogether. Each happily points out that her country had multiple female leaders before them, which eased their path. ‘I saw what you went through and that was just brutal,’ Ardern tells Gillard. ‘I wonder sometimes if our environment was the same as Australia, would I have stuck it out as long.’

Moving as these testimonies are, this is not an easy book to read; in parts it seems like a hastily compiled white paper. This is strange, because it is clear from their previous work that both of its authors know how to write. Fighting Corruption Is Dangerous (2018), Okonjo Iweala’s most recent book, about her second term as finance minister, opens with a vivid retelling of the harrowing abduction of her eighty-three-year-old mother at the hands of kidnappers whose ransom demand was that she resign her ministry on television. Gillard’s My Story (2014), meanwhile, was a frank, lively account of the tumultuous years of her prime ministership (2010–13). So when we must read sentences like the following – ‘How galling, frustrating and infuriating is it that, in the contemporary world, gender can matter so much and to the clear disadvantage of women. It makes you want to cry to the heavens, “What is going on?’’’– the cry to the heavens from the reader is less, ‘What is going on?’ and more, ‘Where is your editor?’

Other passages read like a Facebook post from a loved but overbearing family member: ‘Our message is the exact opposite of beware. Rather, it is GO FOR IT! And yes, we are SHOUTING.’ At one point, we are asked to imagine the authors high-fiving each other. There is a questionable metaphor about prescriptive versus descriptive stereotyping based on the idea of a Chinese woman who does not eat rice. It is desperate stuff.

The book is also notable for what is left out. One can only imagine the kinds of fascinating, uncensored conversations there are to be had between Gillard, who is chair of the Global Partnership for Education, and Okonjo-Iweala, who has led negotiations that secured $18 billion in debt relief for her country and is currently gathering backers for a tilt to become head of the World Trade Organization. But these are not the kinds of insights we are offered in Women and Leadership, which is ultimately an attempt to examine the life of women in the political sphere without grappling with their actual politics.

In a long career, no politician is untouched by accusations of corruption, poor decision-making, or betraying voters. But there should be no comparison between Gillard, who was compelled to appear before a highly dubious royal commission into trade unions headed by Dyson Heydon, of all people, and who was cleared of any wrongdoing (not before being accused of being ‘too prepared’ by the now-disgraced judge, in a textbook act of stereotyping that would not have been out of place as a case study for this book), and Lagarde, who, despite her continued rise in international governance, was convicted of negligence over the misuse of public funds during her term as France’s finance minister, (though she was not sentenced or fined).

It is equally hard to argue for the inclusion of Theresa May, who ordered ‘Go Home’ vans to drive around the United Kingdom terrorising migrants into self-deporting, in a book about whether certain groups of people get unfair treatment. Which is probably why the quotation from May that opens the book is an anecdote about how her leopard-print kitten heels got a woman she once met in a lift into politics.

With a self-avowed sexual predator occupying the White House, a man who won’t even admit to the number of children he has in Downing Street, and a new-look government containing an accused rapist installed by the current resident of the Elysée Palace, there is no doubt that we are in need of a book investigating what our other options might be. Unfortunately, one in which May muses on the inspirational value of her shoes is probably not it.

Comments powered by CComment