- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Becoming better acquainted with an author may give rise to a surprise, or two. For example, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft (author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman) and William Godwin (author of Political Justice) is the author of Frankenstein. Mary Shelley met her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, through his devotion to her father’s anarchist political philosophy. Gaining an awareness of the surprisingly complex threads that link one thinker to the next in dynamic webs of influence is one of the deep pleasures of scholarship.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

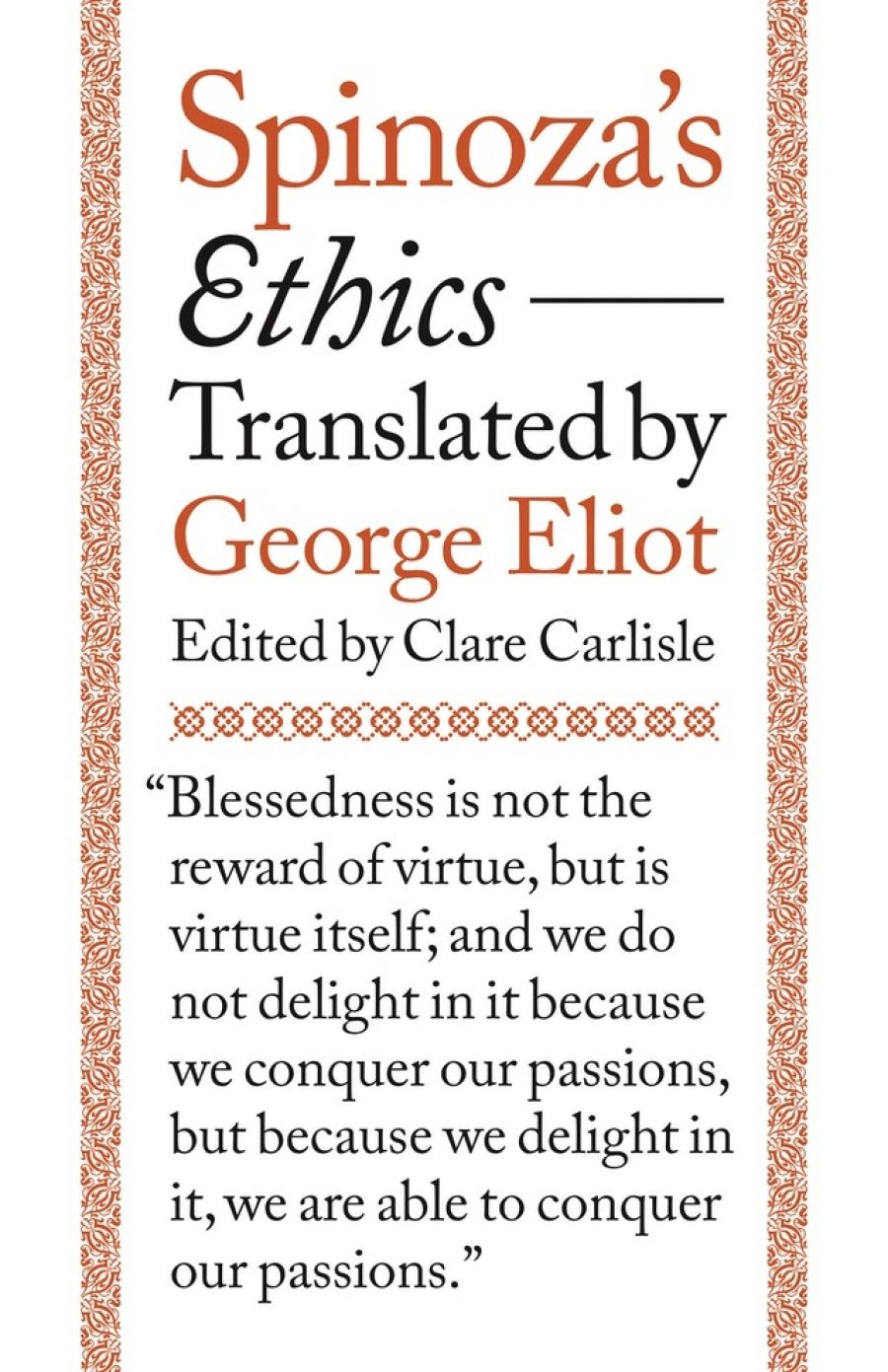

- Book 1 Title: Spinoza’s Ethics

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, $58.99 pb, 381 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/72RbV

The publication of George Eliot’s translation of a major philosophical work, Ethics by Benedict Spinoza (1632–77), opens a cornucopia of such pleasures. Although the publication of this work (reputedly the first English translation from the Latin original) has been delayed by over one hundred and sixty years, it still reads as fresh and lively as any contemporary translation. George Eliot is the nom de plume of Marian Evans (1819–80), author of Adam Bede, Silas Marner, Middlemarch, and Daniel Deronda. She is regarded by many as the finest English novelist of the Victorian period. Before donning the mask of George Eliot, Evans was engaged in other impressive achievements, including editing the influential Westminster Review (1851–54) and translating (from German to English) Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (1854). She came to the task of translating Ethics through her life partner, George Henry Lewes. Lewes (married but estranged from his legal wife) and Evans made, and kept, a lifelong commitment to each other to live as husband and wife. Lewes was a naturalist, journalist, and philosopher who made his living from writing. It was he who made the ill-fated agreement with the publisher Bohn to translate Ethics (a disagreement over the amount to be paid for the translation resulted in Lewes’s angry withdrawal of Evans’s finished manuscript).

It was partly to take refuge from Mrs Grundy, and partly to conduct research for Lewes’s biography of J.W. Goethe, that Evans and Lewes travelled to Weimar and Berlin during 1854, where they could enjoy a peaceful cohabitation. In addition to helping Lewes with his research for Goethe’s biography, Evans translated a major portion of Ethics during this time. It is hard to imagine a more conducive context in which to undertake this work given the strong influence of Spinoza’s philosophy on nineteenth-century German thought. Goethe himself referred to Spinoza’s Ethics as ‘a sedative for my passions’ and said that the study of it had opened for him novel perspectives on nature and morality.

Spinoza scholars have remarked on the puzzle presented by the infatuation of many literary figures with the notoriously intellectually challenging philosophy of Spinoza. In addition to Goethe, the Shelleys, and Coleridge, we can list W. Somerset Maugham, Jorge Luis Borges, Virginia Woolf, and James Joyce. George Eliot sits at the centre of a dense web of Spinoza-influenced literary work. How might this be explained given the incredibly demanding nature of the metaphysical, ontological, and epistemological arguments presented in Ethics? Returning to my earlier point about the pleasant surprises of scholarship, how might we map the guest list of the surprise party that unfolds once one notices the multiple ties between Spinoza and Eliot? Clare Carlisle’s detailed introduction to Eliot’s translation is a learned and engaging guide through the relevant historical, intellectual, philosophical, and literary terrains. The volume also includes some useful appendices. A philosopher herself, Carlisle offers a concise and accessible exegesis of the main arguments of the five parts of Ethics, along with some speculative ideas concerning the likely influence of Spinoza on the fiction writing of George Eliot.

Eliot was no one’s disciple. She was a voracious reader and an exceptional scholar in her own right. Her world view was deeply influenced by Feuerbach, J.S. Mill, Spinoza, and Herbert Spencer, among others, yet that world view is uniquely her own. She shared with Spinoza a conception of ethics that amounts to an endeavour to understand the ways in which beings constituted like us are determined to act by external forces. Many of Eliot’s novels may be read as demonstrations of the inexorable logic that underlies the only apparently chaotic randomness of our lives. Our emotions may lead to foolish behaviour, but they are not, for all that, beyond our ken. As Spinoza observed, our passions are as natural as the weather and, like rain, storms, and thunder, they too have fixed causes. Our passions or emotions may be understood and reformed, and Eliot’s most admirable characters are those who try to regulate their impulses by understanding their causes, or what Carlisle explains in terms of ethology. Carlisle deftly draws out the central issue for both Spinoza and Eliot, namely, how to live the most ethical life possible given the difficulties of gaining knowledge of one’s self, others, and the broader causal system of nature in which all inheres. For both thinkers, an anthropomorphic god who rewards and punishes is a childish illusion. Fully part of nature, we must learn to accept our cosmically insignificant status without disavowing the powers that we do have to together increase our freedom to endure and even to thrive. Eliot’s novels have sometimes attracted accusations of peddling a harsh moralism, as well as pessimism about our ability to accept moral agency and bear responsibility. I prefer to see both Eliot and Spinoza as realists who are clear but non-judgemental about human moral frailty, a frailty captured in the final words of Spinoza’s Ethics: ‘if salvation were close at hand and could be obtained without great labour, how were it possible that it should be neglected by almost all? But everything excellent is as difficult as it is rare.’

Comments powered by CComment