- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

With the possible exception of Jean Baudrillard or Anthony Giddens, it is difficult to think of a contemporary sociologist who has rivalled the international intellectual standing, as well as global fame, of the late Zygmunt Bauman. In his subtle, worldly intelligence, his interdisciplinary engagement, and his poetic cast of mind, Bauman stands out as one of the most influential social thinkers of our time. A distinguished heir to the tradition of radical Marxist criticism, his writings tracked the political contradictions, cultural pressures, and emotional torments of modernity with a uniquely agile understanding. With his scathing critical pen and brilliant socio logical investigations, Bauman unearthed major institutional transformations in capitalism, culture, and communication in a language that disdained all academic boundaries, crossing effortlessly from Marx to mobile phones, from Gramsci to globalisation, and from postmodernism to the privatisation of prisons.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Bauman

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Polity, $51.95 hb, 500 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/PX73R

Culture has never exactly been a strong point of Marxism, and Bauman’s earlier writings were, among other things, an impressive attempt to address anew the interconnections between capitalism, class, and culture. Bauman’s fame, however, rested upon his late writings on modernity and globalisation. Modernity and the Holocaust, his major breakthrough in 1989 just at the point of his retirement from the University of Leeds, is a dark, harrowing study of the deathly consequences of Enlightenment reason. Auschwitz, in Bauman’s eyes, was a result of the civilising mission of modernity; the Final Solution was not a dysfunction of modern rationality but its shocking product. The Holocaust, Bauman argued, was unthinkable outside the twin forces of bureaucracy and technology.

In subsequent books, including Modernity and Ambivalence (1991) and Wasted Lives (2003), Bauman moved from a concern with the historical fortunes of the Jews as victims of modernity to an analysis of the disturbing ways in which postmodern culture cultivates all of us as outsiders, strangers, others. But it was Liquid Modernity (2000), published at the dawn of the new century, which changed everything. His argument that the ‘solid world’ of jobs-for-life and marriages till-death-us-do-part had been replaced by a ‘liquid world’ of short-term contracts and relationships until-further-notice won him a global audience, especially among young readers.

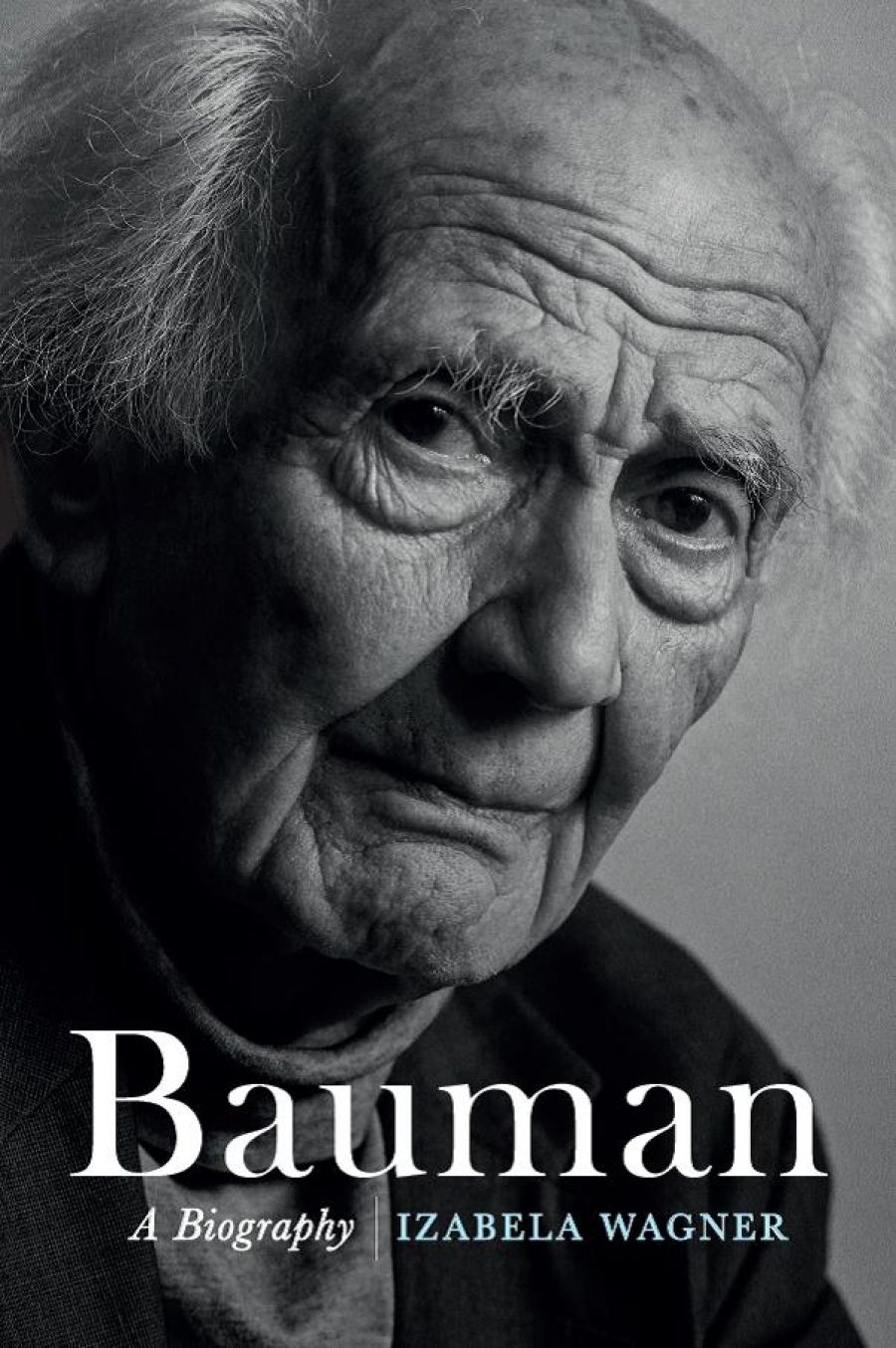

Zygmunt Bauman, 2010 (photograph by Michał Nadolski/Wikimedia Commons)

Zygmunt Bauman, 2010 (photograph by Michał Nadolski/Wikimedia Commons)

Izabela Wagner’s biography of Bauman is impressively erudite, exquisitely researched, and brings its subject vividly to life. She interviewed Bauman towards the end of his life and draws extensively from various archives, including important papers held at the Polish Academy of Science. The result is a sprawling account in which almost everything one might seek to know about Bauman’s life is documented, along with a little more information than is always exactly necessary.

The lives of sociologists, for the most part, tend not to be wildly eventful. But this was not the case with Bauman. A Polish Jew born in Poznań in 1925, he experienced virulent anti-Semitism growing up, the Great Depression (which bankrupted his father, who tried to commit suicide by jumping into a local river when Zygmunt was only a young boy), flight from the Nazis, the life of a refugee in the Soviet Union, combat with the Polish Red Army, incorporation after the war into military intelligence to implement communism à la polonaise, the collapse of Stalinism, ejection from Poland (again) in the anti-Semitic purge of 1968, intellectual celebrity (speaking to packed audiences from Italy to Portugal to Brazil), the adulation of various anti-globalist movements such as Occupy, and, finally, global fame as one of the world’s most celebrated public intellectuals (in his last years, he was summoned by Pope Francis to Assisi to advise the Vatican on combating the ills of global capitalism). As Wagner wryly notes: ‘Were a Hollywood director to put his hand to Bauman’s life he would be accused of “overdoing it”.’

Wagner provides especially brilliant insights into ‘Comrade Bauman’, the postwar period when Bauman worked in counter-espionage for the pro-Soviet government in Poland. Drawing from Polish secret service archives, she traces with great sensitivity tarnished issues in Bauman’s past. She emphasises that the military hierarchy was not always impressed by his performance, failings explained as due to his ‘Semitic origins’. She also has important things to say about the witch-hunt of Bauman by various anti-communist historians and right-wing political groups in the Polish press throughout the final decades of his life.

Wagner is also insightful in tracing Bauman’s rise as a global thinker. This is surely the best account we are likely to get of his daily work routine and intellectual habits. Always at his desk before five a.m., Bauman’s post-retirement output was nothing short of astonishing. Between 2000 and 2010, he wrote at least a book a year and – towards the final years – up to three annually. But for Bauman work and life were deeply interwoven, and he made the most of everything. As Wagner writes: ‘He was what the French define as a bon vivant: he liked to cook, drink, watch TV, listen to music, drink, eat, smoke (too much), feed people (enormously), talk (all the time), entertain (as frequently as possible).’

The late Australian political psychologist Alan Davies argued that a search for safety in abstractions – where the world is treated as a spectacle – is the characteristic emotional mark of theorists. Wagner is not really interested in analysis of personality, preferring what happened over the why. But her recounting of Bauman’s life gives the attentive reader clues as to his flight from organisational life to the realm of ideas. Bauman eschewed professional associations. He disdained institutional sociology. He was a maverick.

What emerges from Wagner’s pages is a certain inscrutability in Bauman. He didn’t like to talk about his personal life. One of the most psychologically telling moments of the book comes from Keith Tester, Bauman’s former PhD student, collaborator, and friend. Interviewed by Wagner, Tester commented: ‘I don’t think I knew Zygmunt – I don’t think there was a “Zygmunt to know”.’ Wagner is oddly uninterested in exploring this, and thus isn’t able to offer any insights into key emotional aspects of her subject’s life.

The roots of this isolation are all but impossible to fathom from Wagner’s biography. But in it you will find a painstakingly comprehensive account of Bauman’s intellectual formation and his daring originality, a kind of voyage around the nature of his sociological enterprise, and a celebration of a truly global public intellectual. Wagner altogether fails, however, to probe Bauman’s inner life. Powerful memories of his father, Maurycy, appear especially haunting. In the final years of his life, Bauman reflected on his father’s bankruptcy and attempted suicide thus: ‘my first, fully my own, vivid unfading recollection: loud knocking at the door ... and my father – unshaven, in a coat soaking and dripping with dirty water, covered with weeds and slime’. There’s something horribly enigmatic in that recollection, which remains for future Bauman biographers to ponder. In the meantime, Wagner has written an indispensable book about the man she rightly calls ‘one of the most read and famous intellectuals of the early twenty-first century’.

Comments powered by CComment