- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

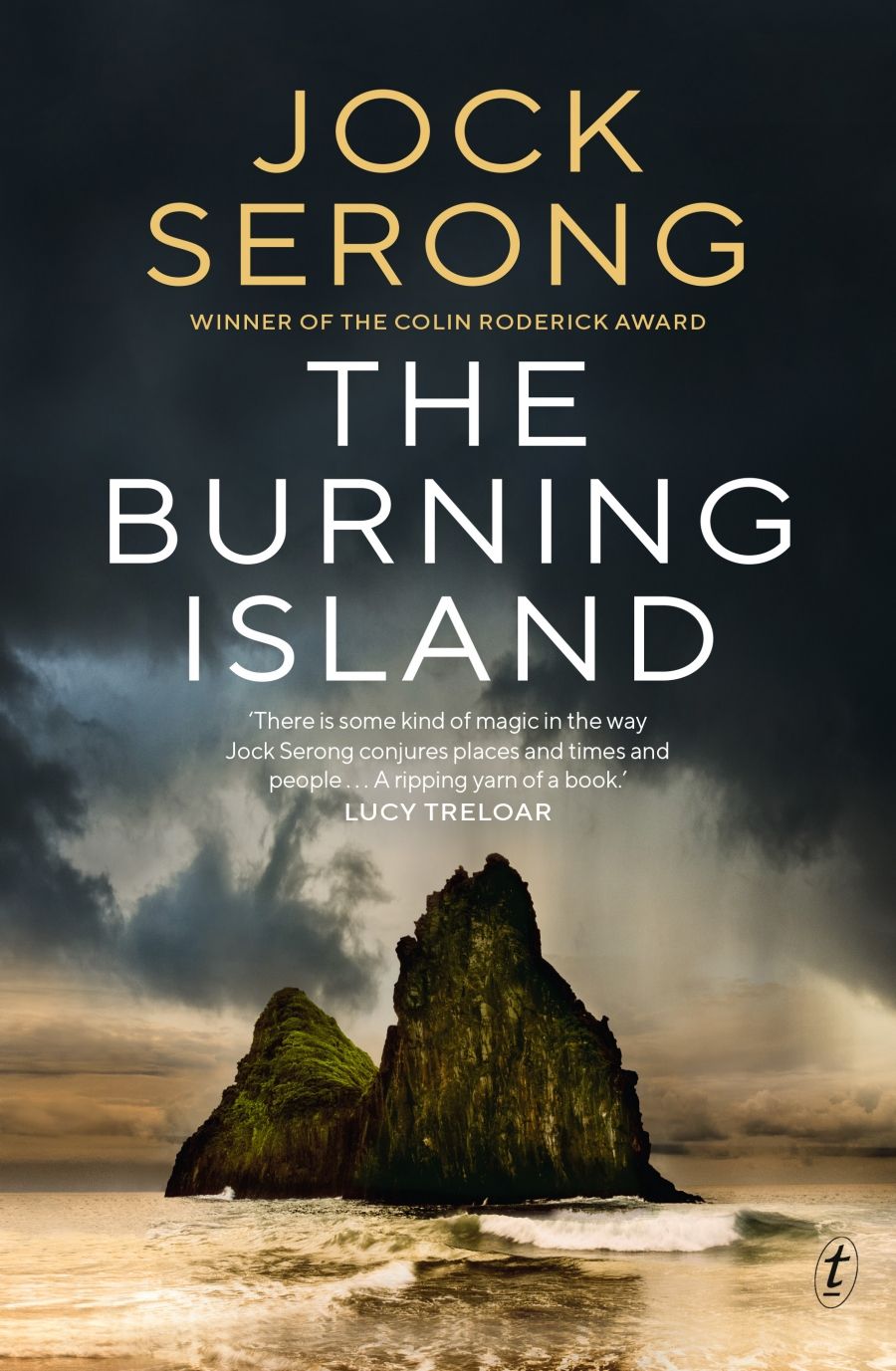

Criminal lawyer turned crime/thriller writer Jock Serong has produced five highly successful novels in as many years. His latest, The Burning Island, is probably his most ambitious to date. Set in 1830, it is part revenge tale, part mystery, part historical snapshot of the Furneaux Islands in Bass Strait, in particular the relationship between European settlers and Indigenous women, who became their ‘island wives’, or tyereelore. It is also the moving story of a daughter’s devotion to her father, with a cracking denouement reminiscent of an Hercule Poirot mystery.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Burning Island

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 348 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/dQ13q

Serong winds the date back to 1830 and changes the ship’s name to the Howrah. The Howrah is owned by a Bengali timber merchant called Srinivas. He approaches thirty-two-year-old governess Eliza Grayling in a bid to enlist the support of her ageing father, Joshua Grayling, in a sea voyage to the Furneaux Islands to try to find the ship and the man he believes is responsible for her loss, a Mister Figge. Srinivas, Joshua, and Mister Figge last encountered each other thirty-three years ago (that story is the subject of Preservation). Suffice to say, the ‘malevolent Mister Figge’ has committed terrible wrongs against both Srinivas and Joshua.

Set in 1830, it is part revenge tale, part mystery, part historical snapshot of the Furneaux Islands in Bass Strait

Srinivas believes that there has been foul play involved in the loss of the Howrah. In an echo of the rumours concerning the Britomart, he tells Eliza that the sealers living in the Furneaux Islands, ‘an isolated society of lawless men’, might ‘not be above committing an outrage’ – luring the boat to destruction, then plundering her and killing her passengers.

Joshua, formerly an aide to Governor Hunter, has had a massive fall from grace and is now a pathetic figure. Described by Eliza as ‘mad, volatile and unpredictable’, he is blind and an alcoholic. Eliza, through whose eyes the story is told, has given up on the prospect of matrimony to devote herself to her father’s care. Her ‘childhood adoration’ for him is long gone; they are now locked in a ‘corrosive game’ in which he drinks to excess and she cleans up the mess and tries to keep him alive.

Joshua leaps at the chance to perform Srinivas’s mission and make the trip, seeing it as an opportunity for revenge against Mister Figge and a chance to give his sad life some meaning. Eliza reluctantly agrees to accompany him on what she sees as a ‘futile and dangerous’ voyage – partly to care for him, partly to relieve the boredom of her own existence. The Furneaux Islands are to her ‘the mythical places I had been told about since childhood’. Srinivas furnishes them with a ship, the Moonbird, an experienced master, Mr Argyle, and two convict crewmen, brothers Angus and Declan Connolly. They are also joined by Dr Henry Gideon, an amateur naturalist interested in collecting specimens from the sea. (As Serong explains in his Author’s Note at the end, all of the characters on the Moonbird are imaginary, unlike some of the real figures who appear later on.)

Serong, well known for his considerable skill at evoking a sense of place in his fiction, paints a vivid picture of the ship, the sea voyage, and life on board. As Eliza fights a losing battle to prevent her father from drinking himself into oblivion, the Moonbird sails south to the Furneaux Islands, stopping at various islands to make enquiries about the missing ship. Here the passengers encounter European sealers and their Indigenous wives, the tyereelore, and learn the complex history of their relationships.

First, they meet Tarenorerer, a real historical figure – a ‘tall and fierce and beautiful’ Indigenous woman abducted from Van Diemen’s Land as a child and sold to sealers, who made her a slave. She escaped, having learnt to speak English and to fire a gun, ‘that knowledge that placed us above them [the European settlers]’. She returned to her people and taught them how to use a gun, then led guerrilla raids on the settlers. She describes to Eliza and the others the depredations committed upon her by white men.

On Gun Carriage Island they encounter a large community of sealers and tyereelore, apparently living happily together. Eliza finds the women ‘garrulous and kind’, good with their children – but ‘hard’. They tell her about their lives and how they help their husbands by doing much of the sealing work. Eliza tries to ask them if they are there of their own free will or if they were abducted, and receives the blunt response – ‘Survival honey, any way you do it’. One woman tells her, ‘you don’t understand it cause you want a simple answer’. Later, Eliza witnesses brutal attempts by white men to round up the women and children and take them away.

While The Burning Island starts out as a crime thriller involving a search for a missing ship and a quest for revenge, it turns into something much more, a carefully researched, nuanced exploration of the history of relations between European men and Indigenous women in the Furneaux Islands, just north of Tasmania, in the 1830s. A minor quibble – a glossary of the Indigenous terms would have assisted the reader (this one, anyway).

Comments powered by CComment