- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It was David Marr who commented that the key character in Gore Vidal’s first memoir, Palimpsest (1995), was not Jimmie Trimble, the boy whom Vidal loved when they were at school and who died, aged eighteen, at the battle for Iwo Jima; nor Vidal’s blind and adored maternal grandfather, Senator Thomas Pryor Gore, whom young Gore would lead onto the floor of the Senate; nor his life partner of half a century, Howard Auster; not even the audacious and polymathic Gore himself. The star of the book was in fact Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, who was dying when Vidal began to write Palimpsest.

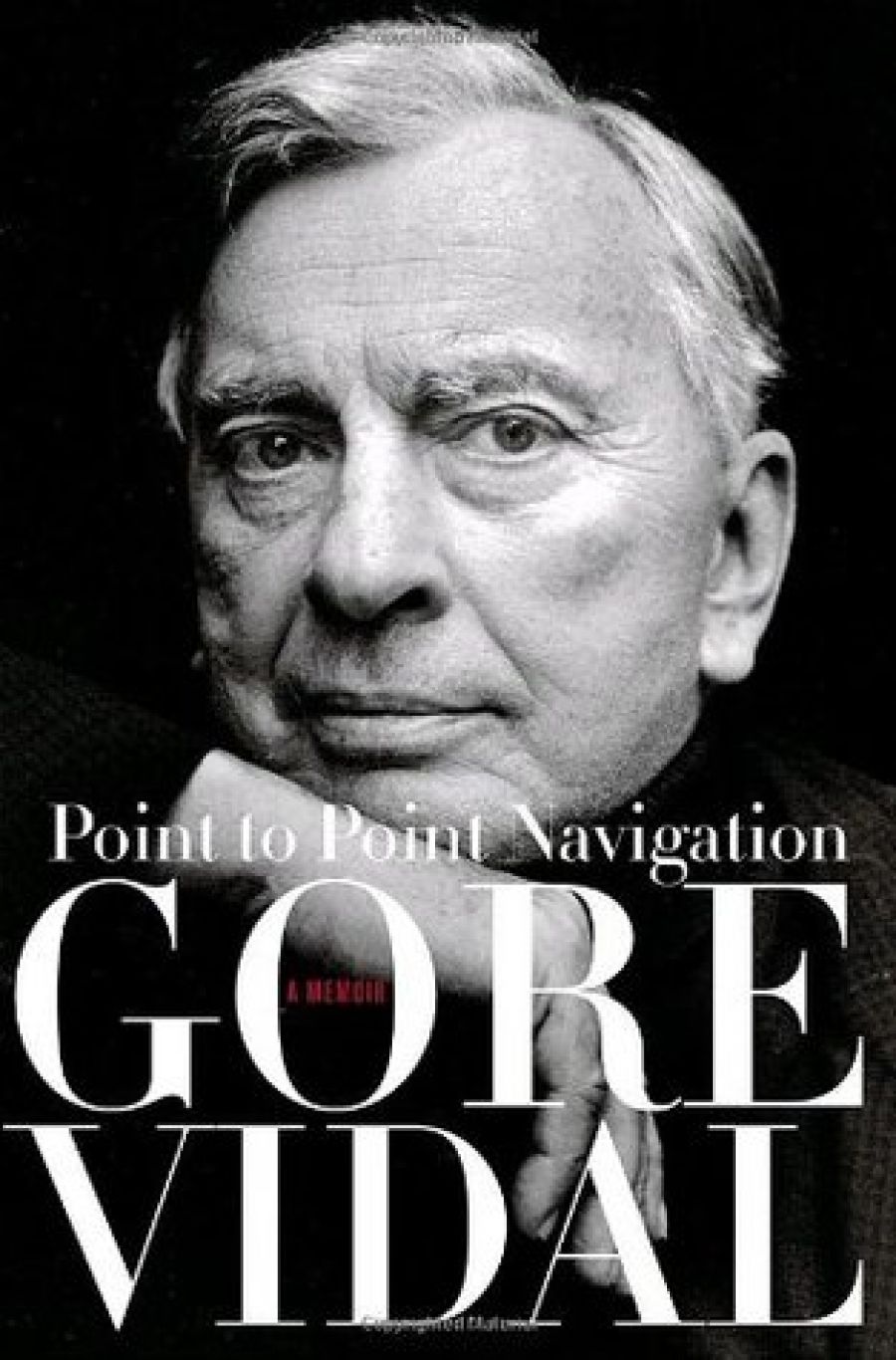

- Book 1 Title: Point to Point Navigation

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir, 1964 to 2006

- Book 1 Biblio: Little, Brown, $49.95 hb, 277 pp

It was David Marr who commented that the key character in Gore Vidal’s first memoir, Palimpsest (1995), was not Jimmie Trimble, the boy whom Vidal loved when they were at school and who died, aged eighteen, at the battle for Iwo Jima; nor Vidal’s blind and adored maternal grandfather, Senator Thomas Pryor Gore, whom young Gore would lead onto the floor of the Senate; nor his life partner of half a century, Howard Auster; not even the audacious and polymathic Gore himself. The star of the book was in fact Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, who was dying when Vidal began to write Palimpsest.

We know of course (Vidal has told us a thousand times) that he and Jackie were briefly and arcanely related by marriage. Palimpsest opens with a wedding at which Jackie, matron of honour to Vidal’s half-sister, shows the virginal bride how to douche after sex. The brilliant young step-somethings often lunch together; the gossip is delicious; Jackie, whose ‘boyish beauty and life-enhancing malice’ delight Vidal, anticipates and dreads her absent husband’s future. There is even an ‘erotic shock’ in a speedboat when they go waterskiing, though Vidal, always guarded about sex, declares that ‘nothing happened’. Even when Robert Kennedy steps in at a 1961 White House party and accuses Vidal of being too familiar with the First Lady, Jackie continues to haunt the book.

The references in this new memoir are sparse, for they never socialised after the contretemps in 1961. According to Vidal, the rupture with the Kennedys did not faze him (‘I was not designed to play attendant lord’), but a constant in this book is the old yearning and ambiguous need for Jackie’s presence in his life. He baulks at Jackie’s attempts to erase him from her past; insists he was there; adduces proof.

Palimpsest ended in 1964, when Vidal was aged thirty-nine. Point to Point Navigation (a term for navigation without a compass, relying on maps) resumes the story and ends on 1 January 2006 (Vidal, as ever, is precise about dates). It has none of the shapeliness that distinguished Palimpsest, a larger and more ambitious book in every sense. Short by Vidal’s standards and yet divided into fifty-fix chapters, Point to Point Navigation darts about all over the place. But the old stateliness is intact: patrician, ironic, derisive.

Many of the stories are familiar, including Vidal’s old feud with the homophobic New York Times, which refused to review his books after The City and the Pillar (1948). Vidal excuses these repetitions: ‘It has been my experience that writers often forget what they have written since the art of writing is a letting go of a piece of one’s mind, and so there is a kind of mental erasure as it finds its place on a page in order to leap to another consciousness like a mutant viral strain.’ But there may be another explanation. Vidal, with his formidable brain and boundless sense of entitlement, refuses to forget or forgive. Combative to the last, he rails against his adversaries. In this he is like Barry Humphries, both brilliant, fearless, aphoristic, vengeful, not to mention endlessly mother-hating. It is so liberating for a memoirist not to need or wish to be liked. As Pope said, ‘The life of a wit is a warfare upon earth.’

Of his biographer, Fred Kaplan (1999), Vidal is curtly dismissive. Truman Capote, ‘a marvellous liar’, gets another serve (‘Although he felt himself to be the heir to Proust, a reference I once made to Madame Verdurin drew a blank’). Vidal is friendlier towards Dennis Altman and finds things to admire in his Gore Vidal’s America (2006), but he still devotes a chapter to supposed mistakes and misreadings in the book. Not all the main characters in Palimpsest reappear. Jimmie Trimble is hardly mentioned, as if it is painful or futile to recall the beautiful boy. Tennessee Williams, whom Vidal dubbed ‘the Glorious Bird’, remains the most vivid creation in his memoirs, but the old friendship wanes because of the playwright’s drug addiction and his ‘night-blooming paranoia’. Vidal’s impossible mother (Nina Gore Vidal Auchincloss Olds) dies in 1978, but that’s about all she does: Vidal hadn’t seen her in twenty years because of her rudeness to Auster. Still, Vidal can’t resist trotting out her great rationale for not seeking a fourth husband: ‘My first husband had three balls. My second, two. My third, one. Even I know not to press my luck.’

Vidal remains a peerless name-dropper. Fellini, for whom he acted in Fellini’s Roma (1972), has a cameo role, weird as any of his characters. We meet Johnny Carson in retirement, ‘better looking than he looked’. Vidal pays court to Eleanor Roosevelt, the veins in her left temple throbbing when she becomes emotional. There is a late glimpse of Nureyev not long before his death, still angry about President Carter’s manner towards him in the White House (‘Very powerful, these Russian curses’). More tedious is the usual tittle-tattle about Garbo in the toilet.

Princess Margaret (already brilliantly depicted in Edward St Aubyn’s novel Some Hope [1994]) is so much more attractive in satirical literature than she was in real life. Her description of Wallis Simpson at the duke’s funeral is classic, as are her confidences about the queen. Clearly, ‘PM’ endeared herself to Vidal by saying of his novel Duluth (1983): ‘I don’t know what there is in me that is so low and base, that I love this book.’

Vidal is the least sentimental of memoirists, but he regrets the loss of two houses: Edgewater, a Greek Revival extravagance on the Hudson River; and La Rondinaia in Ravello, which he sold not long after Howard Auster’s death in 2003. Vidal attributes his obsession with houses to his mother’s cavalier approach to matrimony. He adds to the record about his remarkable grandfather, who sat in the Senate from 1907 to 1937 (one of the shorter terms in the history of that chamber of gerontocrats). Of the United States he is now utterly despairing: ‘Our old original Republic does seem to be well and truly gone.’

Auster’s long illness and treatment are described at some length. There is a tender moment at the end when Auster, who never expected it to last, asks Vidal to embrace him. They kiss on the lips for the first time in half a century. (Like his father, Vidal does not like to be touched.) The success of their partnership he attributes to the absence of sex: ‘… it is easy to sustain a relationship when sex plays no part and impossible, I have observed, when it does.’

Vidal, citing his beloved Montaigne, is fatalistic about death, and waits for diabetes to ‘do its gaudy thing’. While immensely proud of his oeuvre and his pedigree, he is resigned to the eclipse of the famous author and to the wide-spread indifference to newspapers and commentators. ‘Today, where literature was, movies are.’

As for Jackie? There is a last encounter in 1975, soon after Aristotle Onassis’s death. Vidal, celebrating his fiftieth birthday, is staying at the Ritz in London. Jackie, widowed again and wearing a white trench coat, joins Vidal and Auster in the lift: an awkward moment, which Vidal – in a brilliantly symbolic moment – chooses to ignore by turning to the mirror and removing a smudge of ink from his brow. ‘[Jackie] sighed in her best Marilyn Monroe voice, “Bye-bye” and vanished into Piccadilly.’

It all has the fatal authenticity of a dream.