- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journalism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Flight from Boganville

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Before you settle into this ‘random history of the twenty-first century’, grab an atlas: Andrew Mueller is one well-travelled hack. A fatalist philatelist, he has spent most of his career collecting the types of stamps that adorn passports, not envelopes. In I Wouldn’t Start from Here, Mueller reports on and from some of the most exotic sites of international strife imaginable: Jerusalem, Baghdad, Gaza, Kabul. There are also trips to places of lesser renown, aspirational statelets and breakaway provinces in countries as far-flung as Georgia (Abkhazia). All of which, as his publishers congratulate him in their press release, is ‘[n]ot bad for a guy who originally hails from Wagga Wagga’.

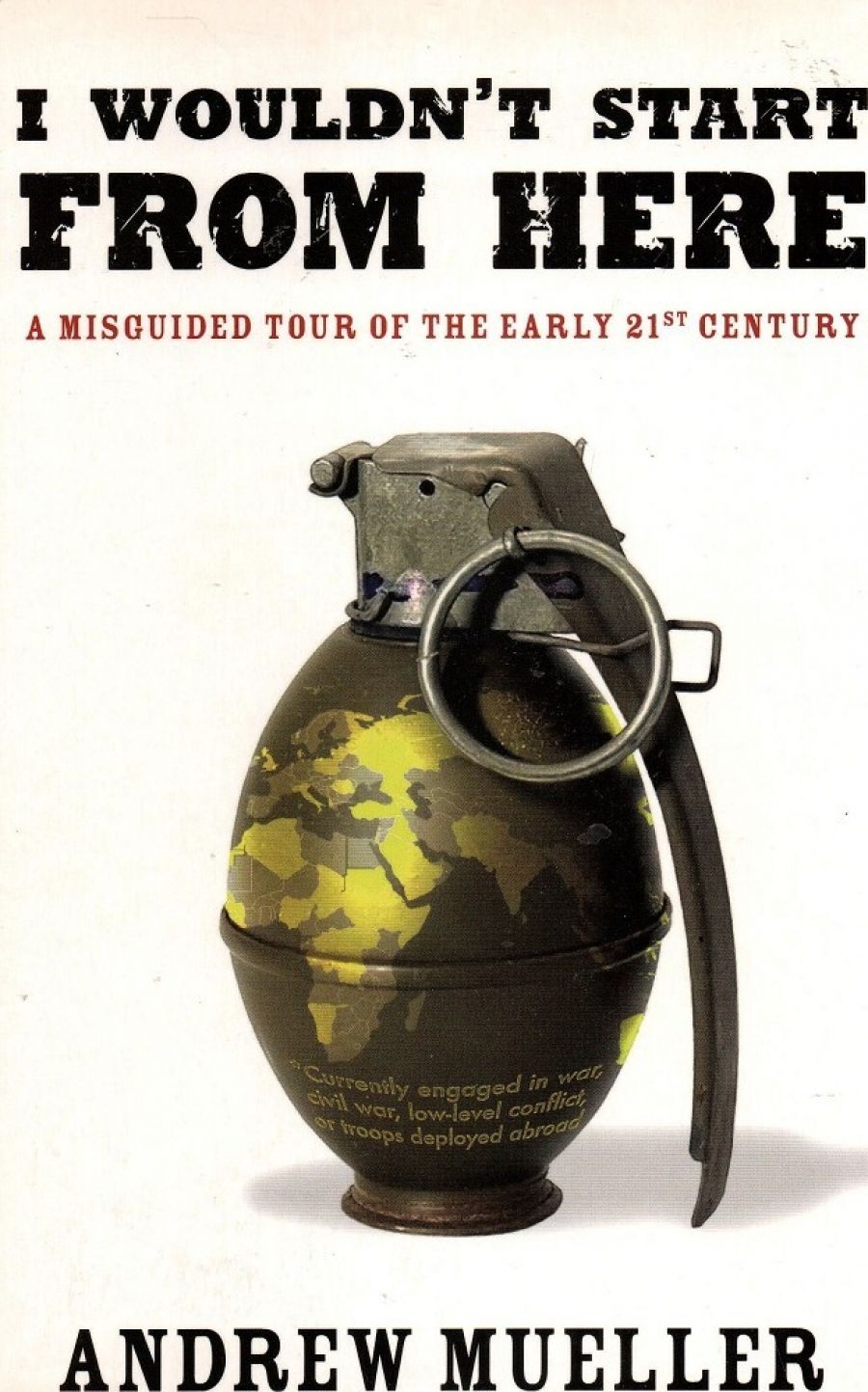

- Book 1 Title: I Wouldn't Start From Here

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Misguided tour of the early 21st century

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $35 pb, 400 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Mueller seems like a jaunty type, as country boys often do, and his prose is infused with a lightness, or a breeziness perhaps, that tends to leaven the often turgid situations to which he is so pathologically attracted. He is incurably curious about societies that just cannot get along. ‘The peaceful, prosperous, free and civilised world is a nice place to live,’ he states. ‘But I wouldn’t want to visit it.’

The book is a non-chronologically organised collection of his dispatches for various and generally venerable publications such as Independent on Sunday, The Sunday Times, openDemocracy.net and The Face. In the spirit of Hunter S. Thompson, they showcase reportage with running commentary, though I didn’t sense the depth of perspective and insight that characterised the work of the good doctor. This seems to be a result of Mueller’s reluctance to engage intimately with his readers, beyond the odd lovelorn confessional, which, coupled with his incessant sarcasm, sometimes makes it hard to gauge his sincerity.

This sarcasm was a sticking point with me. While I appreciated his ability to encapsulate complicated situations with a deft quote, this tendency looked at times like disdainful reductionism. Mueller boggles at ‘the willingness of people to smash up their own neighbourhood over whether or not blokes in daft hats can walk down a street whacking a drum’, and notes that the ‘theory ... that a cause can be worth fighting for but not risking injury for, had been born in the deserts of Iraq’. One of these sentences seems to me a genuine pearl of wisdom, the other a shallow abstraction of a complex situation.

It may be that I am banging my own drum here. When I found my views in accordance with Mueller’s, I responded enthusiastically to his jaundiced bombast. It was usually when I disagreed with him that his Bonoesque confidence in his own assertions really grated. Such authority may be the just reward for a man who, unlike me but like Bono, has been there and done it in the theatres of war and discord. It is just that his BYO morality makes it seem that too often he is in attendance only to see, not to learn.

Halfway through the book, I began to wonder whether the author was pitching his observations at somebody younger than myself (twenty-eight), somebody not yet set on a trajectory, still open to the whims of fate and inspiration. I pictured myself as a teenager nursing a talent for arranging words in a small country town (like Wagga Wagga, say), and imagined the effect of a book such as this early in my life could have had on my subsequent journey. The world can seem a very confined space when you are landlocked in Boganville (which has none of the attractions of the South Pacific, nor any of the strife, admittedly), but it only takes one person to provide an example that any number can follow: and Mueller is the embodiment of what can happen with a fire in the belly and a desire to write out loud.

Read in this light, the book offers a kind of manifesto for making oneself a writer; an entertaining, high-spirited ‘How To’ for aspiring reporters: How To Secure Visas For Régimes That Don’t Like Journalists; How To Stay Connected To The Outside World Whilst Under Arrest In Africa – and so on. Mueller is a resourceful, creative, dogged and courageous exemplar of what it takes to lift oneself from obscurity in country New South Wales to infamy in any number of internecine states.

If such a reading looks like a back-handed compliment, I am loath to retract it, because this may be just the sort of book that Generation Y (if that is what we are up to) needs if it is going to be able to preach to coming generations about how it made a positive impact on the world. I don’t mean to suggest that Mueller’s work is irrelevant to everybody else, just that it may be vital for that most maligned aggregation.

Comments powered by CComment