- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the late twentieth century, museums throughout the world faced a number of challenges. Confronted with a plethora of flashy new technologies, they struggled to overcome a perception of irrelevance and fustiness. Bureaucrats demanded that museums pay their way, entertain the masses, and meet the growing expectations for instant gratification and information without effort.

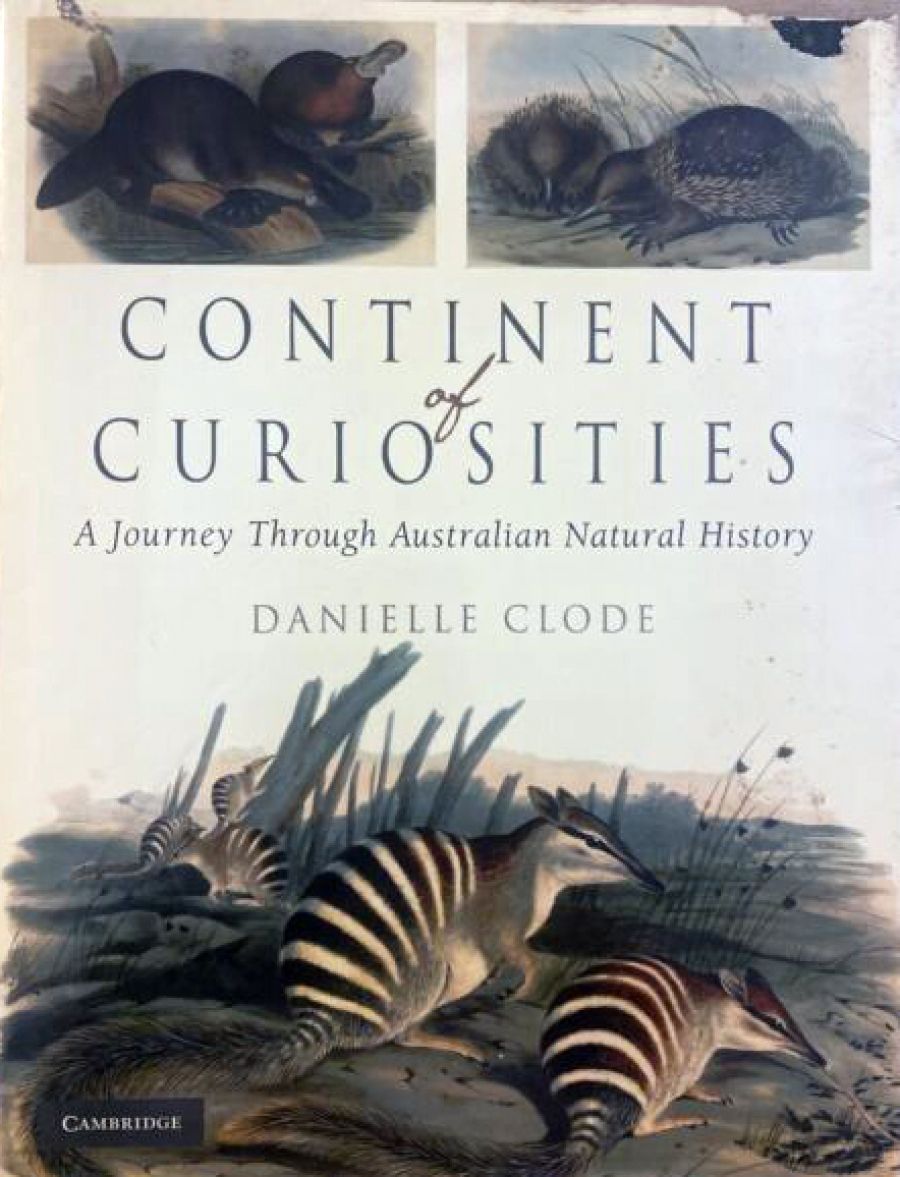

- Book 1 Title: Continent of Curiosities

- Book 1 Subtitle: A journey through Australian natural history

- Book 1 Biblio: CUP, $59.95 hb, 212 pp

The Museum of Victoria seemed to suffer more than most. Having been housed ‘temporarily’ in the Art Gallery for more than one hundred years, it was desperately in need of a new building and identity. After watching the museum being used as a political football by successive state governments, we ended up with a dramatic, if somewhat impractical, new building and an organisation unsure of its identity (is it a scientific establishment, an art gallery, a zoo or a venue for ‘major events’?). The emphasis seemed to swing away from science towards popular culture (a wedding dress from a television soap opera was promoted as a major drawcard). The critical roles of museums as repositories for scientific specimens, their careful and systematic curation, documentation and classification, and the inspiration of future scientists, took a back seat. Museum Victoria has struggled ever since to get the balance right. It has lost key scientific positions (for example, several curators replaced by a collection manager) and has consequently lost relevance in the scientific community.

Danielle Clode’s latest book is thus timely and refreshing. It reminds us of the real value of museums by using examples drawn from the collections of Museum Victoria to illustrate how scientific knowledge advances, how the scientific value of the collections can never be underestimated, and how vital is the role of curating the collections on behalf of future generations, to ensure the effective scientific use of the collections to advance knowledge and conservation.

Clode’s strategy is clever and effective; she uses eleven seemingly inconsequential specimens, thoughtfully selected from the natural history collection that totals some fifteen million items, to introduce eleven wide-ranging and eclectic essays on aspects of science history, beginning with Melbourne’s recent past and going back to the beginnings of life, at least one thousand million years ago.

The titles of the eleven chapters are reminiscent of those in Agatha Christie novels, and the storylines are all about the slow, painstaking and multi-faceted detective work that characterises most science. ‘Curious Collections’ is an essay on the human need to collect and classify – the primary role of museums; ‘A Beast Named Su’ charts the history of European discovery of Australia and its marsupials; ‘Local Knowledge’ investigates the contribution that indigenous Australians made (and continue to make) to biological survey and understanding; ‘Water, Water Everywhere’ is a very topical history of Melbourne’s unmatched water catchment areas and sewage system; ‘Forests of Fire’ describes the ecology of the magnificent Mountain Ash forests in the ranges north-east of Melbourne – the world’s tallest hardwood forests; ‘The Mysteries of the Reappearing Possums’ recounts the scientific discovery and fluctuating fortunes of Leadbeater’s Possum and the Mountain Pygmy Possum; ‘The Case of the Missing Mollusc’ is an overdue account of how a nondescript fossil bivalve from the cliffs at Jan Juc provided a critical missing link in the evolutionary record that helped Darwinism triumph over Lamarckian and creationist beliefs (despite the best efforts of Professor McCoy, director of the museum at the time); ‘Brainbox’ explores how palaeontologists are able to derive information on the biology and ecology of a South Gippsland dinosaur from a fossil fragment of its skull that shows the imprint of the beast’s brain; ‘The Ape Case’ explores the debate about man’s place in nature that erupted following the publication of Charles Darwin’s revolutionary theory of speciation via natural selection; ‘Lines in the Sea’ describes the rise of the discipline of biogeography, including the relative roles of Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace; ‘Shifting Continents’ looks at the role of museum specimens in elucidating the theory of continental drift; and ‘Life on Mars’ investigates the occurrence of ancient biological material in meteorites.

This book is a fascinating collection of stories, all with local connections. Complex issues are clearly explained, with sensible use of text ‘boxes’ to provide the necessary background information. Good use is also made of relevant historical paintings, photographs and maps. It is undoubtedly popular science writing of a high standard. Unfortunately, the impact of the book is reduced by a surprising number of errors, which, given the large number of museum and university scientists listed in the acknowledgments, and the reputation of the publisher, should have been avoided. Some examples: in the table on page six, the eutherian flying squirrel has somehow morphed into a marsupial Squirrel Glider; on page sixteen, the generic names for wallabies are decades out of date; the illustration on page thirty-six labelled Greater Bilby is actually a Sandhill Dunnart taken from the report of the Horn Expedition, and it was not drawn by Gerhard Kreft (sic); Ken Simpson did not use Aboriginal knowledge to conduct broad-scale surveys of bilbies, but Ken Johnson did; gannets do not occur anywhere near as far south as Macquarie Island. There are also rather too many typos, including misspelling the names of contributors and species. These sorts of errors suggest that the manuscript was not scrutinised by a knowledgeable zoologist – a great pity because they detract from an otherwise highly satisfying collection of essays.

Comments powered by CComment