- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Beverley Kingston reviews 'Lucy Osburn, A Lady Displaced' by Judith Godden

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nightingale nurse

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

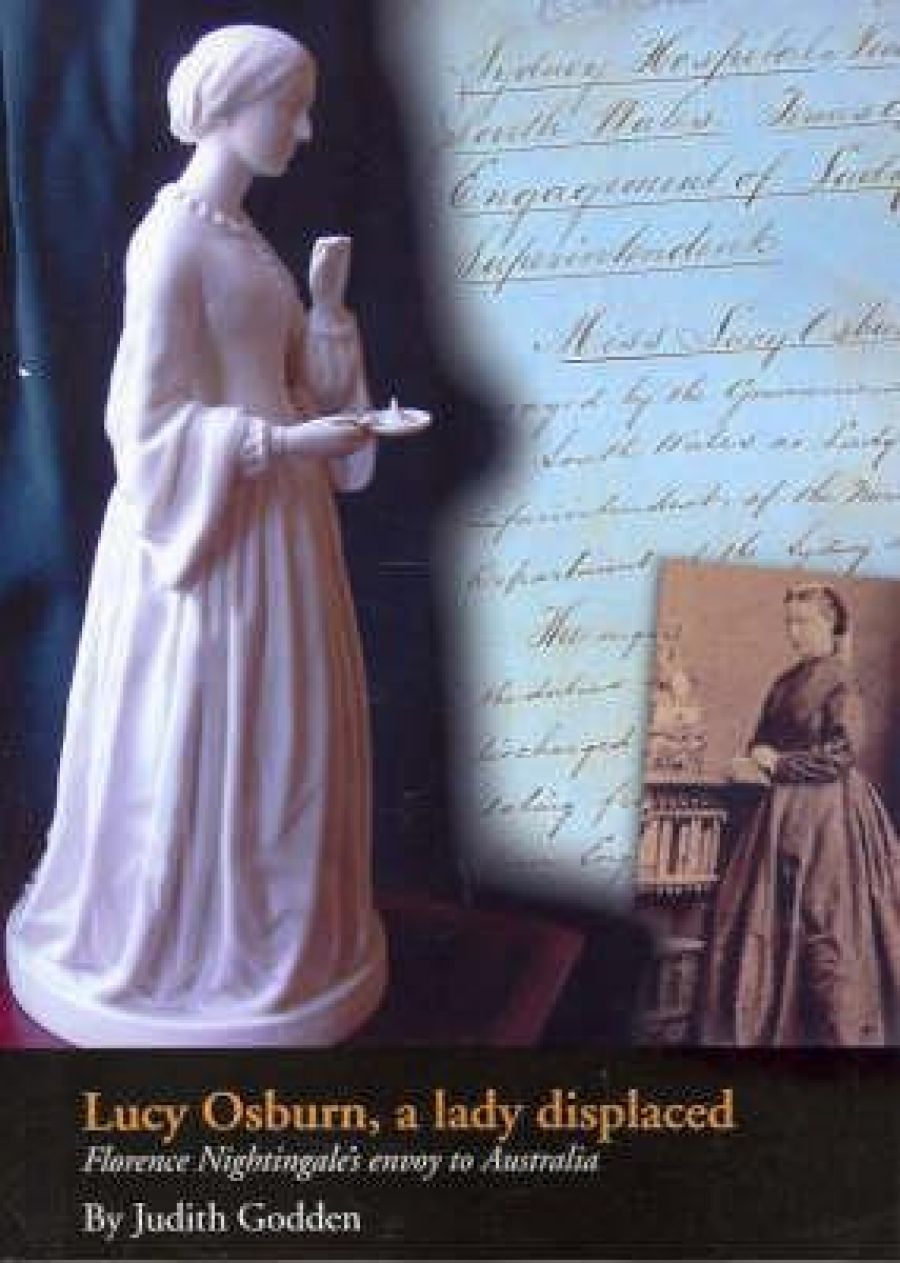

The cover of Judith Godden’s biography of Lucy Osburn, the founder of modern nursing in Australia, is dominated by a ghostly white statuette of Florence Nightingale. Lucy herself appears in a bottom corner, photographed with a book in hand, an insignificant figure dressed in black silk, with a white cap over a severe hairstyle. At times, it seems as if Nightingale is going to overshadow the book, too. But despite her largely unsuccessful attempts to carry out the wishes of the ‘lady with the lamp’ in New South Wales, Osburn did succeed in creating conditions whereby scientific practices could be introduced into nursing in Australia, though she failed to convince the medical establishment that women could be trusted with medical knowledge or were capable of managing hospitals.

- Book 1 Title: Lucy Osburn, A Lady Displaced

- Book 1 Subtitle: Florence Nightingale's envoy to Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $34.95 pb, 373 pp

Lucy was the younger daughter of William and Ann Osburn of Leeds. Her father had a degree from Cambridge, a passion for Egyptology, and saw himself as a public intellectual, though his income came from his family’s wine and spirit business. First bankruptcy then their mother’s death meant that the family scattered. From about the age of six Lucy, often unhappy, was brought up by relatives. It became clear to her that if she was to achieve anything like self-respect or independence she would need employment that enabled her to support herself economically. She accepted a post as companion/governess to a doctor and his wife and family posted to Jerusalem. There, it seems, she gained some initial training as a nurse, probably helping Dr Atkinson in his surgery.

Back in England, she had hardly begun her training as a Nightingale nurse when she was chosen to lead the team to be sent to Sydney at the request of Henry Parkes. There was no one else available among the trainees who could pass as a lady, deemed by Nightingale an essential quality for leadership. As it turned out, Lucy herself was barely able to cope with the class demands of her position in Sydney. Her letters to Nightingale were almost pathetically preoccupied with the attention she received from the wife of the governor and other high-status women who were kind to her. Their private comments, however, sometimes suggested that they found her quaint, a little above herself. At the same time, her isolation made her extremely vulnerable, especially as the male doctors at the infirmary were determined that nurses should do nothing of a medical character and actively hindered the kind of nursing Nightingale training was intended to provide.

The account of Lucy’s years in Sydney from 1868 to 1885 becomes a bemusing portrait of the jealousies, pettiness and hypocrisies of a small, inward-looking society. Not only was there a great deal of emphasis and ceremony based on status, but the divisions between Catholic and Protestant stimulated poisonous and scurrilous gossip. Because she called herself the ‘Lady Superintendent’ and wore austere habit-like dresses, Lucy was accused of planning to convert her nurses to some kind of pseudo-Catholic order. When she ordered the incineration of a box of vermin-infested bibles, she was suspected of ulterior religious motives. She had responsibility but no power. Somehow she was expected to make everything at the hospital run smoothly, as if she were both wife and mother to the board. Initially paid less than some of the women who served as post-mistresses, her salary rose over time and she began to save money, investing in shares and buying a house in Homebush (which she settled on her faithful housekeeper Annie Parker when the latter married in 1884). In poor health from over-work and frustrated by her powerlessness, she resigned suddenly in 1884 rather than face yet another, as it turned out, groundless inquiry. She returned to London via New Zealand, Canada and Europe and began to renew an earlier interest in district nursing. From 1888 she became superintendent of district nursing in Newington and Walworth in the east-end of London, for which in 1890 she was named a Queen’s Nurse, but a few months later she was diagnosed with diabetes. Before the discovery of insulin, there was no effective treatment for diabetes, and death usually followed within two years. Lucy Osburn died on 22 December 1891.

Despite Godden’s careful account, Osburn remains something of an enigma. This is partly because of the unimaginable constraints imposed on an unmarried woman in those days, but also because most of the evidence for her life consists of official documents, some politically motivated reports and inquiries, and her surviving letters, many of which were also semi-political, reporting on achievements or seeking assistance. There are very few letters written familiarly and unselfconsciously to relatives or friends. But Judith Godden’s summing up in her concluding chapter is immensely helpful and unlikely to be bettered.

Comments powered by CComment