- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cut off from the stream

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

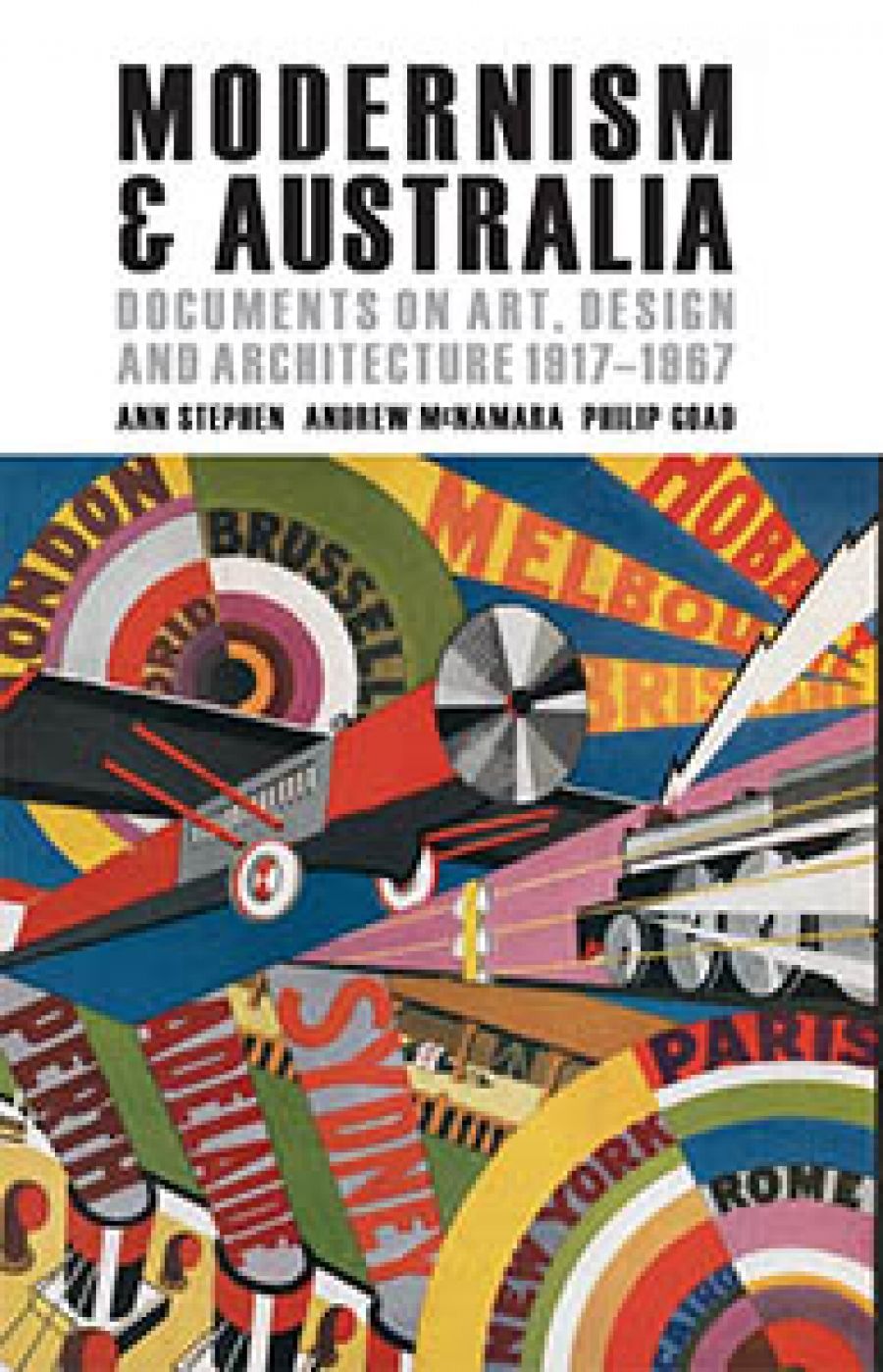

A striking work by Adrian Feint and Hera Roberts appears on the cover of Modernism & Australia: Documents on Art, Design and Architecture 1917–1967. It shows an aeroplane, a locomotive and an ocean liner travelling in opposite directions through a vivid landscape of radiating lines and concentric circles. On the circular forms, which are reminiscent of abstract paintings by the French artist Robert Delaunay, we read the legend ‘Paris, Rome, New York, Cairo’; on the diagonal lines, ‘Hobart, Melbourne, Brisbane’. This 1928 work is typically modernist for its celebration of the exciting possibilities of modern technology, and in its use of bold colour areas and geometric shapes. It is also a declaration of a perceived, or wished-for, globalisation of culture, which Feint and Roberts, by adopting styles from international modernism, have realised in the work’s very design.

- Book 1 Title: Modernism & Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Documents on art, design and architecture 1917–1967

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $65 pb, 1039 pp

Unlike the image of dynamic international exchange projected by this work, Australian painters and sculptors in the period 1917–67 were rarely in a position to enter into a global art scene, and there was stubborn institutional resistance in this country to most forms of modernist art. It is telling, therefore, that the work which adorns this vast collection of writings about modernism in Australia was originally the cover of an issue of The Home, a magazine concentrating on fashion, architecture, interior design, photography and graphic design. As the editors of this new anthology point out, in comparison to their colleagues in the fine arts, Australian architects and designers were better connected internationally and had more success in convincing their compatriots of the relevance and significance of modernism.

Although this account is not new (the important role played by interior design in disseminating modernism in Australia has been understood for some time), this publication will do much to reorientate thinking about a crucial period in the history of Australian design, architecture and art, and will become an indispensable text for researchers, students and teachers in the field. The three editors – Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, and Philip Goad – each distinguished specialists in one or more fields covered in the book, have taken the opportunity provided by the assembling of this anthology to broaden a discussion that is usually conducted within one or other sphere of practice. This is a significant achievement in itself, and it accords well with the spirit of those modernists who campaigned for a synthesis of the arts. Another important achievement by the editors is their eloquent argument, made largely through the voices of others, that the reception of modernism in this country was a complex affair.

What do the selected texts reveal about that reception? A major theme is the question of whether Australians were, in any meaningful sense, fully engaged and up to date with the international development of modernism. This had been answered in the affirmative by Feint and Robert’s magazine cover, and is demonstrated by the openness to global artistic currents of early twentieth-century practitioners such as the architect John D. Moore, painter Roland Wakelin, and ceramicist Anne Dangar, all of whom spent considerable periods of time in Europe. A number of important texts which document visits by prominent international figures, such as Walter Gropius and Hans Albers, or the work of migrants to Australia, such as Harry Seidler and Ludwig Hirschfield-Mack – both of whom studied at the Bauhaus – demonstrate the substantial flow of ideas between this country and the northern hemisphere. The writings of many of the artists, architects and designers attest to the sophistication of their interpretations of modernist ideas, whether in Grace Crowley’s Mondrian-like exhortation in 1936 to integrate all elements of the canvas, or Seidler’s discussion in 1949 of the relationship between transparency and dematerialisation in architecture.

However, other documents tell a different story. For the architect Geoffrey Moline, mid-century Australia lacked ‘the easy interchange of ideas and competitive thought that so stimulates activities, especially in the United States of America’. For Ian Burn in 1967, ‘[i]n contemporary Australia there exists a comparative lack of the stimuli from ideas for the artist’. The sculptor Robert Klippel, in a lament repeated more often by fine artists than designers, noted that the ‘price one must pay’ for living in Australia ‘is to be cut off from the stream of European thought and ideas’. Nevertheless, he added, the gain is that ‘there is everything to be done and no tradition to be broken down’.

This formulation of the Australian situation, which the editors describe as the inversion theory of Australian artistic identity, was a common one among those writing in defence of, or against, modernism. In the writings of Frederick McCubbin and Robert Hughes, for example, different as they are from one another, a perceived lack in Australia, such as distance from the old world, is inverted rhetorically so that it becomes a perceived advantage in terms of authenticity or freedom from the burden of the past. As Bernard Smith points out in the extract from Australian Painting Today (1962), reprinted in the anthology, this idea of isolation was a myth which disavowed the often substantial connections between Australian and European art. Although Smith argued that it was largely conservative European traditions rather than modernism that had held sway, in the 1960s international abstraction had attracted so many Australian followers that he could liken it, in a moment of paranoia, to a ‘Juggernaut intent upon destroying every other kind of art in its path’. The editors’ selection of texts, and their intelligent commentary on them in the introduction and in the extended remarks on each individual extract, make it possible to see precisely how varied feelings were about Australia’s relationship to international modernism.

Another theme this anthology draws attention to is the relationship between the disciplines of architecture, design and art, and the broader socio-political sphere. The importance of this connection was uppermost in the minds of many European modernists who opposed the idea of art for art’s sake and strongly believed in the social and political efficacy of their art. In this regard, Australian modernists were no exception: designers and architects such as G. Sydney Jones, with his radical urban-planning designs, or Robin Boyd, in his call for affordable housing, repeat over and over the mantra that the modernist style of building and planning is democratic, for the people, non-élitist. Recorded here, too, are the acrimonious disputes during the 1940s between Albert Tucker and Noel Counihan about which version of modernism was more anti-fascist and more ideologically sound from a Marxist perspective: abstract or figurative art, radically iconoclastic art or that linked to the tradition of image making. Socio-political arguments were also, however, the stock-in-trade of anti-modernists, such as when J.S. MacDonald, praising the work of Arthur Streeton for showing ‘the way in which life should be lived in Australia, with the maximum of flocks and the minimum of factories’, promulgated a view of Australians as ‘the elect of the world, the last of the pastoralists, the thoroughbred Aryans in all their nobility’. A similar tone was struck in the 1942 text ‘The Jew in Modern Painting’, by Lionel Lindsay, which rehashed anti-Semitic boilerplate about the corrupting influence of Jewish dealers on modern art, and could have been lifted directly from the art column of an official newspaper in Nazi Germany. As this anthology documents, there was no shortage of artistic discussions among prominent political figures in Australia. In 1939 H.V. Evatt launched the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society at the National Gallery of Victoria with a broadside at Menzies’ conservative Australian Academy of Art for its tendency to ‘obstruct the spread of modern culture in Australia’, and a refreshingly intelligent and open-minded defence of modernism:

What will be called ‘distortion’ may be a means of creating an emotional response at a higher level … What will often be derided as abstract may convey a spiritual beauty of form and colour that is independent of, and transcends, the expression of material persons and things.

For the sake of comparison, we may recall Prime Minister John Howard’s rather narrower conception of art outlined in a speech at the National Gallery of Australia (1998):

Art should not shout at us, it should speak of us as we are. It should allow us to express ourselves and it should at all times be a representation to the world of what Australia is and what Australia has achieved.

There have been, and will always be, criticisms of a book like this. Omission is usually the first charge, and many will find key figures left out of this survey. As the editors explain, the focus was not on fame but on writers whose thinking was particularly astute or representative. Sometimes one feels, while reading the texts, that the choice of extracts, based on impact in Australia, doesn’t really do justice to the individuals concerned. For example, Buckminster Fuller is represented by a second-hand account of a lecture given in Australia, whereas one of his own writings would surely have been more appropriate. Michel Seuphor’s entries for Crowley, Mary Webb, Ralph Balson and Frank Hinder in A Dictionary of Abstract Painting (1957) add nothing to our understanding of their work: the choice of this text seems to be merely to demonstrate the artists’ international status. Similarly with the American Edgar Kaufmann Jr on design: was his rather anodyne article chosen only because it was published in Australia? But if the story behind this anthology is correct – that Australians were mostly in touch with international developments – why focus so much on Australian publications when contemporary readers had access to international publications and also travelled? Finally, although there are good reasons to exclude images from a work like this, from space limitations to copyright costs, at times the cited authors’ explicit discussion of works of art, objects or buildings could have benefited from illustration.

That said, this volume is a monumental achievement on the part of the editors, and the publishers are to be commended for bringing this important series of texts together in one place, some of which are extremely rare and have never before been published. It is an essential reference work which will soon be appearing on reading lists at a university near you.

Comments powered by CComment