- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: ‘A mutinous and ferocious grace: Nick Cave and trauma’s aftermath' by Felicity Plunkett

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

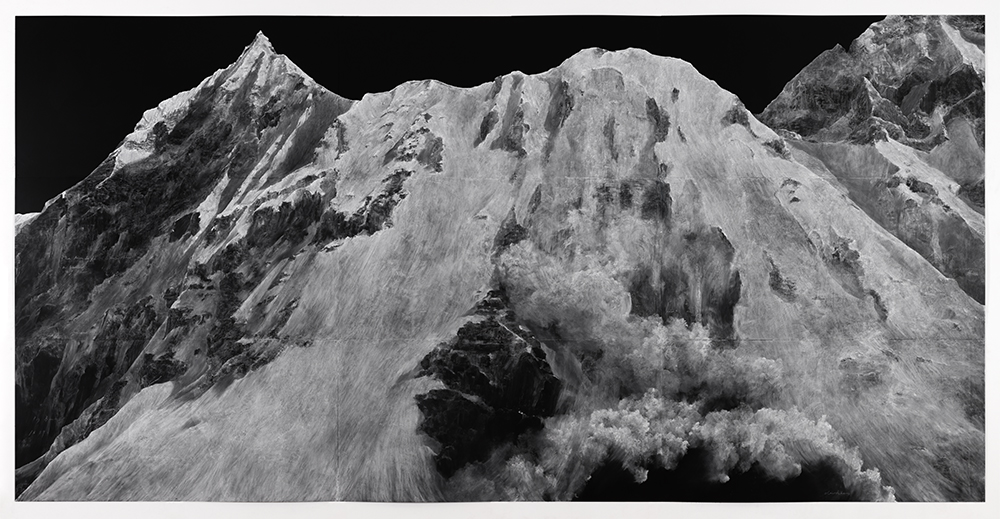

It begins with a projected haze of ocean horizon. In this blurry liminal space, silence is misted with anticipation, like the moment before an echo comes back empty, right across the sea. Then a close-up of multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis’s hands unpicking tranquillity’s fabric, each piano note a loosened stitch ...

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds perform at Open’er Festival on 4 July 2018 in Gdynia, Poland (Ewa Burdynska-Michnam, East News sp. z o.o. Alamy Stock Photo)

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds perform at Open’er Festival on 4 July 2018 in Gdynia, Poland (Ewa Burdynska-Michnam, East News sp. z o.o. Alamy Stock Photo)

It begins with a projected haze of ocean horizon. In this blurry liminal space, silence is misted with anticipation, like the moment before an echo comes back empty, right across the sea. Then a close-up of multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis’s hands unpicking tranquillity’s fabric, each piano note a loosened stitch.

The machinery of the Bad Seeds emerges: scarred midriffs of violins and guitars, a shimmer of pinstripes and a flourish of the pocket squares favoured by the rock dandy, fingers heavily ringed. The stage is set with percussion, keyboards, flute, a grand piano: jangle and spark itching to launch. Deep concentration: the glance among colleagues who have worked together for decades, in the moment between rehearsal and performance when everything is scripted but anything can happen.

Nick Cave steps onstage, slim, suited, singing: The things we love, we love, we love, we lose, the last word snuffing itself out, almost inaudible. There’s a sob edging the note and sky-raised eyes: there are powers at play more forceful than we. Austere instrumentation drops into silence as he continues: I’m begging you please to come home now, come home now. He is right on the edge, singing convalesce into palpable empathy, mask of twigs and clay, hands reaching towards him: with my voice, I am calling you. Deep within this mood of aftermath, something is stirring. In the echo of witness – the audience, still, holding each syllable – a stretch and wrench of sung words and an eerie swoop of synth and harmonies signal the crossing to a new part of Cave’s creative life.

On 12 April 2018, Distant Sky, a live concert film of Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds screened once in cinemas around the world. Made in October 2017 at the Royal Arena in Copenhagen and directed by David Barnard, it captured Australian-born musician and writer Nick Cave and his band The Bad Seeds playing to an audience of sixteen thousand people.

The concert was part of a tour following the 2016 release of the band’s sixteenth studio album. Skeleton Tree was recorded over eighteen months. During this time, in July 2015, Arthur Cave, the fifteen-year-old son of Cave and his wife, Susie Bick, died after an accidental fall at Ovingdean Gap near their home in Brighton, England. To avoid promotional interviews, Cave commissioned Australian director Andrew Dominik to make a documentary. Dominik describes One More Time With Feeling as ‘a practical solution to a practical problem’. The thought of interviews ‘made [Cave] feel sick, because he was going to have to discuss the context of the record with a whole bunch of journalists. That prospect was very alarming to him. His instinct in making the film was one of self-preservation: it was a way to talk about what happened, but there was a certain safety in doing it with someone he knew.’ Cave found himself caught between the need for silence and the need to speak: the human instinct for privacy and the artist’s sense of a responsibility to say something. ‘The idea of a traditional interview,’ writes Dominik, ‘was simply unfeasible but … he felt a need to let the people who cared about his music understand the basic state of things.’

Dominik describes Cave as ‘trapped’ and needing ‘to do something – anything – to at least give the impression of forward movement’. In the process, an unexpected kernel appeared. The resulting film is more than a holding bay, and more than a way out of a trap. It grows from self-preservation into documenting Cave’s crafting, from elegy and empathy, a new creative mode.

The film explores the final stages of Skeleton Tree’s production, capturing the band’s work that continues through, and comes to embody, Cave’s mourning. Dominik shot the film in 3D and black and white using a specially made camera: a ‘massive, lumbering piece of equipment that’s almost comic lack of mobility added to the eerie drift of the film itself’. Cumbersome, awkward machinery that doesn’t always work seems apt for capturing the impact of trauma and the lurching dynamics of resilience. The angles are often askew, shots out of focus. Cave is split and mirrored – in the sheen of a grand piano or in a bathroom mirror, itself reflecting a line from Skeleton Tree’s ‘Magneto’: And in the bathroom mirror I see me vomit in the sink / And all through the house we hear the hyena’s hymns.

‘Magneto’, the song that gives the film its name, is about intimacy: In love, in love, I love, you love, I laugh, you laugh / I move, you move / And one more time with feeling. It evokes the way pain is necessarily shared to some extent by those in love: I’m sawn in half becomes we saw each other in half.

The plan was that Dominik would shoot the film but that Cave could veto anything. Dominik asked him to record his thoughts on relevant subjects to form a voice-over. As Cave watched the footage and recorded responses on his iPhone, he escaped the restriction of enforced or inspired public words on one side and silence on the other. Poetry and reflection opened the path to a more intuitive approach.

In a review in the Guardian, Andrew Pulver, who admits to never having been a massive Cave fan, sees the film as a moving collage, but also as a ‘spectacle’. His description of some writing on Cave as ‘hagiographical’ sets the tone for the review. It seems, especially bizarrely under the circumstances, sniffy or sneering, though sniffing and sneering recur in critical work on Cave. But then, so does a hagiographical tone. The trouble is that neither the demonising mode nor the hagiographical captures the paradoxical transparency an artist can find when afforded privacy and spaciousness.

In Rolling Stone, Dominik expresses the fear he felt when, not long after Arthur’s death, Cave contacted him to say he wanted to talk: ‘I was terrified at the thought of receiving that phone call … I just didn’t know whether I would be equipped to deal with somebody who I knew was going to be in state that was unimaginable to me.’ How we might imagine or witness something we have not experienced is a central human question. The film bears witness to mourning. It studies both Susie Bick and Nick Cave, the former reserved and private, the latter used to working in public and with words.

Susie Bick, Nick and Earl Cave, Rick Woollard, and Andrew Dominik in One More Time with Feeling (photograph by Kerry Brown)

Susie Bick, Nick and Earl Cave, Rick Woollard, and Andrew Dominik in One More Time with Feeling (photograph by Kerry Brown)

Cave’s meta-commentary contains tones familiar from his decades of songwriting. It is allusive, wry, self-deprecating, risky, intelligent, tender, and darkly comedic. New, though, is the ruminative lens through which he tries to convey some of grief’s impact. At one point, he has to overdub a vocal, something he describes as ‘some kind of torture’ because it’s disconnected from the music’s original energy and has to be grafted back on. His commentary does something similar, stitching itself back through the film. This mirrors trauma’s aftermath, when finding ways to reattach the self cut loose from life-as-we-know-it is part of a solitary labour. Cave explores ‘what happens when an event occurs that is so catastrophic … that you just change. You change from the known person to an unknown person. So that when you look at yourself in the mirror, you recognise the person that you were, but the person inside the skin is a different person.’

One More Time With Feeling is about the conjunction of mourning and creativity. In his study of elegy, Poetry of Mourning: The modern elegy from Hardy to Heaney (1994), Jahan Ramazani discusses the sublimation of mourning and elegy’s increasing role as ‘refuge from the social denial of grief’. Elegiac, One More Time With Feeling openly places grief in the contexts of work and love. It documents collaboration and friendship, especially between Cave and Warren Ellis, part of The Bad Seeds since 1994 (a decade after its formation in 1983) and Cave’s collaborator on projects including the band Grinderman and numerous film scores. Ellis’s uneasy comment that he won’t discuss other people’s private lives prefaces the film. Extreme close-ups of Ellis watching Cave struggle with his singing or tacking a song to the music’s fabric are just as telling as this protective remark. ‘What would I do without Warren?’ reflects Cave. The sense of Ellis’s vigilance shapes Dominik’s work. It was Ellis who watched the film and assured Cave and Bick it worked.

One More Time With Feeling shows slivers and flashes of how ineptly many people relate to trauma (Cave’s word). Ramazani charts the rise of ‘an increasing neglect of the dead and mourning’ that comes to look ‘more and more like active denial’. He quotes social anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer that ‘it would seem to be believed, quite sincerely, that sensible, rational men and women can keep their mourning under complete control by strength of will or character so that it need be given no public expression’. This suppression of mourning has endangered consolation. Sydney writer Mark Mordue describes how people faced with other people’s grief feel ‘shamed by inadequate condolences’. Shame and clumsy gestures on one hand – flowers, cards, casseroles – and shame and evasion on the other.

Early on, Cave gently corrects Dominik’s comment that lives have a similar arc. Of course, broadly, they do. But there are extreme experiences many people don’t have. Cave is quietly emphatic. Sure, our lives have a broad common outline, but ‘the arc can be very different’. Cave describes being in a bakery, and someone approaching ‘with his kind eyes’, saying: ‘We are all with you.’ Now, ‘all the bakery is looking at you with kind eyes’. This is both beautiful and repugnant: ‘When,’ Cave asks himself, ‘did you become an object of pity?’ Part of the artistic and personal triumph of Cave’s work on Skeleton Tree and beyond is about bracing for and embracing the stumbling kindness of other people’s consolation.

Cave has a way of turning the film’s vignettes into something larger. When he struggles vocally, he worries ‘I think I’m losing my voice’, a moment critics have noted for its metaphoric resonance. In the figurative, where Cave is very much at home, he stretches it into an improvised poem about losing things: ‘My voice. My iPhone. My judgement. My memory, maybe.’

This catalogue, with its twist from the arch into the dark, the self-admonishing shove at the end, recalls Elizabeth Bishop’s acute villanelle ‘One Art’, which begins ‘The art of losing isn’t hard to master’. It works through losses – tuning up from ‘lost door keys’, past ‘places and names’ and ‘my mother’s watch’ – until it reaches its final stanza:

– Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Cave doubtless knows Bishop’s famous poem, and his is ghosted by hers. He has articulated poetry’s place in his creative life in a series of online letters The Red Hand Files: ‘I try to read, at the very least, a half-hour of poetry a day, before I begin to do my own writing’, adding: ‘It jimmies open the imagination, making the mind more receptive to metaphor and abstraction and serves as a bridge from the reasoned mind to a stranger state of alertness, in case that precious idea decides to drop by.’

Cave has written about lost love many times. Now, though, when he evokes ‘the lost things that have so much mass and so much weight’, he’s well beyond the terrain that Bishop conjures. Yet a similar jagged barked command to the self – Write it! – runs through the documentary, and this phase of Cave’s career.

The film documents two people – Cave and his wife (Arthur’s twin, Earl, appears at several delicate moments, but is shielded by his parents, even as he shields them) – faced with suffering on a catastrophic scale.

It would be naïve to suggest that trauma’s gifts include creative renewal. Trauma is a stingy benefactor and if pain is the exchange for its benefits, anyone sane would go without. Cave is clear that trauma is ‘extremely damaging to the creative process’. In his interview with Mark Mordue, he speaks of how trauma ‘fills up all the space. It fills up your body. It’s like a physical thing. You can feel it pressing against the insides of your fingers. There’s just no room for the luxury of creation.’ In one of the letters, he describes ‘the uncontainable and merciless dimensions of grief’.

And yet, in a poem he recites in the film, Cave says: ‘There is more paradise in hell than we’ve been told.’ In spite of its ironic undertones, this highlights the possibility of renewal through a process of transmutation almost as unimaginable as other people’s trauma. Poetry might jimmy the imagination open. Trauma’s less delicate approach can achieve the same result. Sometimes, together, trauma and poetry can produce a radical openness.

Cave is now undertaking a series of ‘In Conversation’ events, opening up a fearless dialogue with his audiences. The Red Hand Files respond to fans’ questions: ‘You can ask me anything. There will be no moderator. This will be between you and me. Let’s see what happens.’ This is a version of the ‘Ask Me Anything’ (AMA) sessions hosted in various forums, made close and intimate by the epistolary form and the use of a website rather than social media. Cave writes about creativity, love songs (‘maybe songs are the parlance of love’, maybe they are ‘small unassuming love bombs’), and the letters themselves: ‘When I started the Files I had a small idea that people were in need of a more thoughtful discourse. I felt a similar need. I felt that social media was by its nature undermining both nuance and connectivity. I thought that, for my fans at least, The Red Hand Files could go some way to remedy that.’

The letters return to loss. In response to a question about sensing the presence of his son, he writes that whatever this presence is, its basis is ideas, which might be the bridge to new ways of being in the world: ‘It is their impossible and ghostly hands that draw us back to the world from which we were jettisoned; better now and unimaginably changed.’

The next letter can arrive at any time. When it does, it will have weight and light. This time, the echo comes back full. Skeleton Tree approaches a tentative conclusion – a very quiet one, its final song threaded with the refrain it’s alright now and the image of a candle in a window – maybe you can see? Cave is like Wallace Steven’s ‘scholar of one candle’, effulgence and fear his companions as he works.

Almost prophetically, The Bad Seeds’ previous album, Push the Sky Away, expresses the hope that Cave’s new work limns. The title song quietly urges us to keep on pushing the sky away, while the wild, wired surrealism of ‘Jubilee Street’ has Cave singing: I’m transforming. I’m vibrating. I’m glowing. I’m flying. Look at me now.

Cave’s talent is undimmed and this exhilarating staged ‘I’ is evident in Distant Skies. But in the dark, by the light of that single candle, he has found something else – something urgent, vulnerable, and profoundly kind. He uses the word ‘need’ several times in the letters, writing about audiences and artists’ need for connection, an uncertainty that ‘propels us forward’.

In January 2019, Cave replies to a father raising a small daughter after his wife’s death. A shared understanding of the house haunted by hyena hymns allows Cave to speak in this new way, consoling and empathetic. He has described actively living our lives ‘in the service of others’ and using ‘what power we have to reduce each other’s suffering’ as the ‘remedy to our own suffering’ and ‘the essential antidote for loneliness’. He depicts his wife: ‘defiant and scoured clean by grief; a woman with a mutinous and ferocious grace, now more open, daring and creative than ever; a woman who has simply defied the cosmic odds and bloomed’. Everywhere in these responses, and Cave’s new work, are the currents of his own mutinous and ferocious grace:

We are alone but we are also connected in a personhood of suffering. We have reached out to each other, with nothing to offer, but an acceptance of our mutual despair. We must understand that the depths of our anguish signal the heights we can, in time, attain. This is an extraordinary faith. It makes demands on the vast reserves of inner-strength that you may not even be aware of. But they are there.