- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

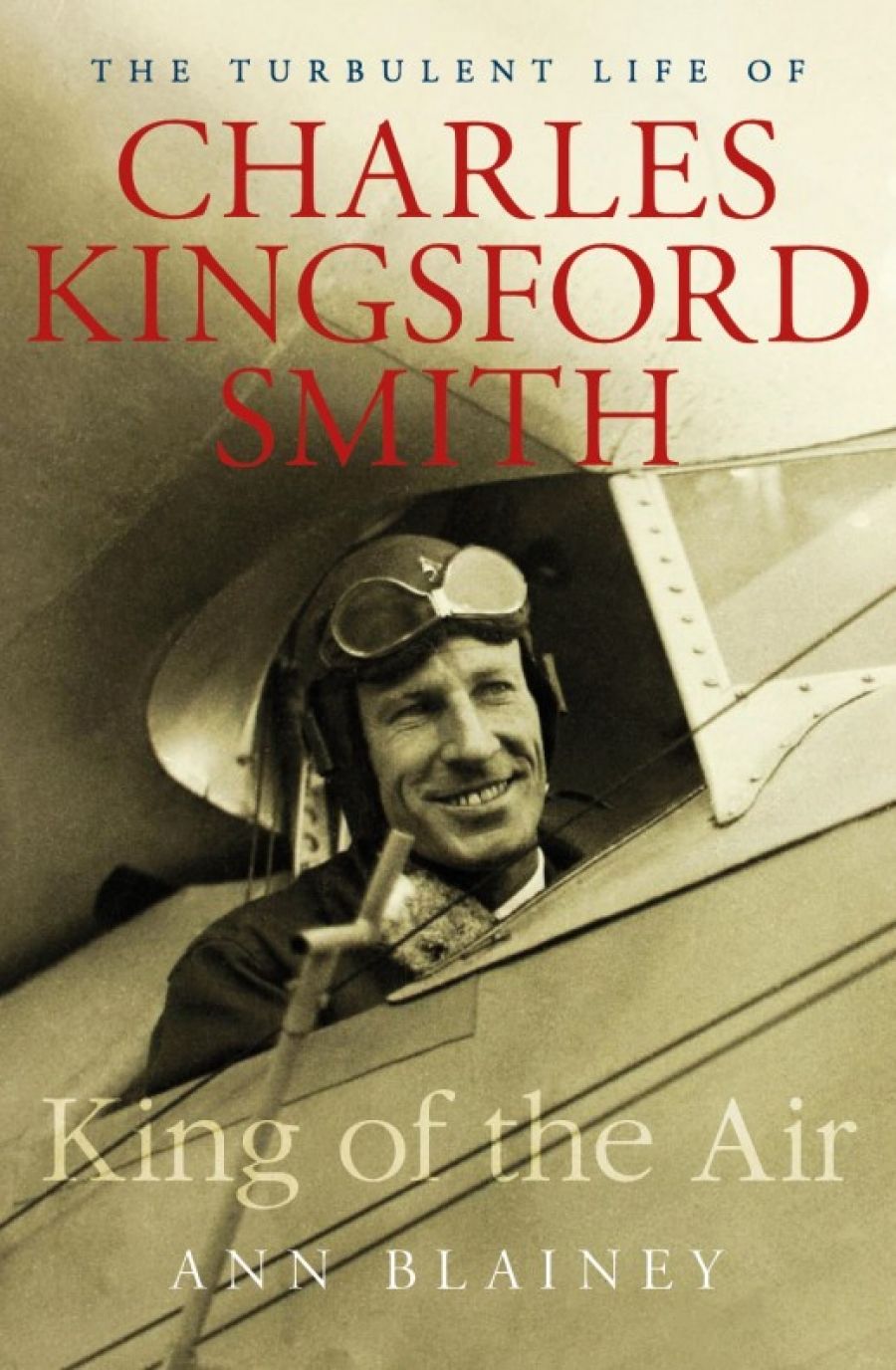

- Custom Article Title: Michael McGirr reviews <em>King of the Air: The turbulent life of Charles Kingsford Smith</em> by Ann Blainey

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

People spent a lot of time looking for the pioneering aviator Charles Kingsford Smith. When he disappeared for the final time in 1935 just south of Myanmar, then known as Burma, he was just thirty-eight but felt ancient. Hopeful rescuers came from far and wide, but their efforts were not rewarded ...

- Book 1 Title: King of the Air: The turbulent life of Charles Kingsford Smith

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $49.99 hb, 384 pp, 9781760641078

Smith was the product of the protestant upper-middle class. His father was a banker with a blemished record, he was a member of the cathedral choir at St Andrew’s in Sydney, and his family lived in respectable houses in places such as Neutral Bay and Longueville. He narrowly escaped drowning at Bondi when he was nine. As with so many in his generation, it is interesting to ponder what might have happened if the Great War had not sunk its talons into him. Smith was a motorcycle dispatch rider at Gallipoli and on the Western Front before joining the Royal Flying Corps. Blainey never uses a term such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but it is hard to resist the thought that his subsequent restlessness, frenetic approach to relationships and bouts of deep depression had their roots in what he witnessed.

The tone of some of Smithy’s letters home provides a clue. He uses the ‘boys’ own’ adventure language of the time to disguise an ordeal. For example, he describes an air battle as a ‘dickens of a fight’ in which ‘I had bad luck just after bagging my bird. My gun jammed and I had to leave the scrap and tootle off home.’ He landed with a bullet hole in his collar. Later, he lost part of a leg and was lucky to survive. He received a Military Cross which made him feel ‘frightfully bucked.’ Blainey is not fooled by the chipper language he used to keep up the spirits of both his parents and himself. When he returned from war, she notes: ‘Sometimes Smithy was angry and resentful, and sometimes he was depressed. Sometimes he thought about the war and many incidents he would rather have forgotten rose to the surface of his mind.’ In particular, he was haunted by the ‘unearthly joy’ he felt after a slaughter of enemy soldiers.

Charles Kingsford Smith and Mary Powell in 1930

Charles Kingsford Smith and Mary Powell in 1930

Smithy self-medicated with alcohol and sex. After a string of hapless affairs, he married Thelma Corboy at short notice. The couple spent little time together, and, when they did, Smithy seemed to be never far from the bottle. For Thelma, it was lonely experience. His second marriage, to Mary Powell, was buoyed by media adulation and the trappings of fame. But there was never any question that Smithy would settle down or accommodate the interests of his wife, whatever they may have been. He persisted with what he disparagingly called ‘harmless little flirtations’. He was a largely absent father. Blainey lays out the facts unapologetically, observing the haphazard emotional life of her subject in compelling detail. She is not inclined to move further back to write about the enduring trauma of those who returned from war. Or is it possible that Smithy was just a lad with very limited sense of emotional responsibility? He compulsively kept returning to the air to attempt challenges that left him with panic attacks and miseries of various kinds. Was celebrity another drug to ease the pain?

In some ways, it appears that the closest relationship that Charles Kingsford Smith ever had was with his legendary plane, The Southern Cross, a three-engined Fokker that Smithy referred to with great affection as ‘the old bus’. Indeed, this became the title of his memoir. Blainey does a fine job in describing the proclivities of this fragile piece of machinery. On its famous crossing of the Pacific Ocean in 1928, with Charles Ulm as co-pilot, the crew sat in wicker chairs that were not even fastened to the floor. There were no seatbelts. The airmen were tossed around, unable to speak above the noise. A friend wrote that the plane ‘responds to his touch like a horse to its master’. He described Smith as ‘literally holding her in the air with his hands and feet, juggling, coaxing her to do it, and getting the extra response nobody else could get from the machine’. There is no doubt that Smithy’s skill saved lives.

Ann Blainey is a pleasure to read and this biography is superbly researched and substantiated. It ends at the moment of Smithy’s death, unwilling to venture into the decades that turned the man into a legend. Unlike her subject, Blainey works within clear boundaries.

Comments powered by CComment