- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

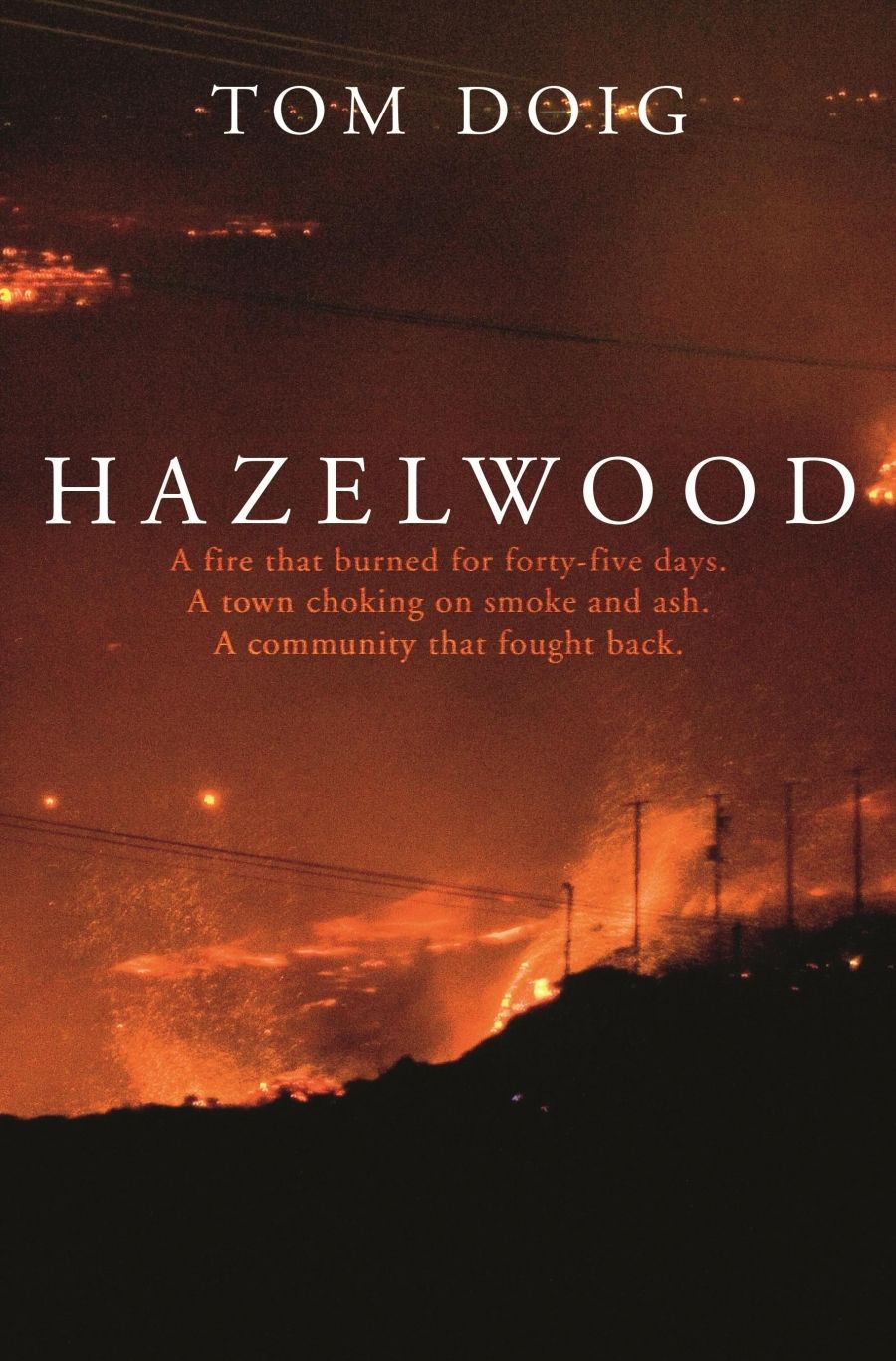

- Custom Article Title: Alistair Thomson reviews <em>Hazelwood</em> by Tom Doig

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Tom Doig’s Hazelwood begins with Scott Morrison proclaiming to Parliament, ‘This is coal. Don’t be afraid … It won’t hurt you’, and concludes, 284 riveting pages later, that ‘the Australian coal industry doesn’t just cause disasters – it is a disaster’. In February 2014, during ‘the worst drought and heatwave south-eastern Australia had ...

- Book 1 Title: Hazelwood

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 304 pp, 9780143793342

After about three months the job was finished and David found another job. By November ‘he didn’t feel quite right’. His head throbbed, his chest ached, a short walk was exhausting. ‘I felt like an old man.’ David’s lung function now tested at forty per cent of normal. A scan showed a ‘white mass’ in David’s lungs and he was diagnosed with extreme ‘pulmonary fibrosis’, an irreversible and incurable build-up of scar tissue in the lungs caused by exposure to tiny ‘PM2.5’ particles in coal smoke. The insurers rejected his WorkCover claim on the grounds that he had not ‘sustained an injury arising out of or in the course of your employment’.

Briggs was one of ninety-five Latrobe Valley men and women interviewed by Doig over several years and seventy-two days spent in the Valley (Hazelwood mine company executives refused interviews, and company staff were instructed not to talk about their experiences). These oral history interviews are the heart of Doig’s book, with personal stories woven through the narrative and then backed up by the documentary record of local media, government records and official inquiries.

The decommissioned Hazelwood Power Station, a brown coal-fuelled thermal power plant (photograph by Stephen Edmonds/Wikimedia Commons)

The decommissioned Hazelwood Power Station, a brown coal-fuelled thermal power plant (photograph by Stephen Edmonds/Wikimedia Commons)

Together, the evidence of testimony and documents confirms a litany of disastrous misjudgements, incompetence, and negligence. Led by Sir John Monash in the 1920s, Victoria’s State Electricity Commission (SEC) began the creation of coal mines and power stations in the Latrobe Valley. In 1945, when the SEC proposed to demolish and relocate the town of Morwell so that it could dig the gigantic Hazelwood open-cut mine, the state government responded to pressure from Morwell residents and left the town intact just four hundred metres from the mine, ignoring SEC requirements for a minimum one-mile buffer zone. In 1977 and again in 1994, following mine fires, the SEC ignored recommendations for improved fire protection sprinklers. The diversion of the Morwell River, and the construction of a highway between town and mine, undermined the water table and caused cracks and sinkholes at the town’s edge, which was slowly slipping towards the mine. Recommendations to protect worked-out coal-faces with clay capping were ignored; undergrowth was left to spread; forests of fire-prone eucalypts were planted near the mine. Before, and especially after, privatisation of the SEC in 1996, maintenance was neglected. Although the working mine and power station were well guarded, the worked-out sections were an ‘accident waiting to happen’ (the company was ‘only interested in protecting the assets that were making them money’). Staff who could see the problem did not want to raise their concerns for fear the mine would be closed. When the mine fire started, during a week of extreme fire danger, senior staff were on holiday, the power for the water-protection systems failed, and there were no maps or signs to help the first responders fight the fire – which got away. As Doig argues, ‘One of the worst industrial disasters Victoria has ever experienced’ should never have happened.

Hazelwood is also a story about ‘one of the worst public health disasters in Australia’, and about a community fighting for its rights. As soon as the fire started, people living just across from the mine began to feel the effects of toxic smoke and ash, with throbbing headaches and rasping coughs. Chickens died and chemically burned pet dogs bled from every cavity. Local and state health officials said there ‘wasn’t much to be worried about’, but Tracie Lund from the Morwell Neighbourhood House began to keep a record of sufferers and symptoms. Wendy Lund, ‘one of the least political people around’, helped set up Voices of the Valley to organise mass protests and media campaigns. Eventually, after nineteen days, the Chief Health Officer relented and recommended that vulnerable people should relocate. By then, for many, the damage was done. When the first Hazelwood Inquiry failed to recognise the extent of health damage, Voices of the Valley gathered death statistics from local papers and persuaded the newly elected Andrews state Labor government to initiate a second Inquiry, which confirmed that at least twenty-three deaths could be attributed to the effects of smoke and ash and set up a long-term study about the effects of the fire.

Meanwhile, the French electricity company that owned Hazelwood decided that the costs of making the mine safe were too great, closed the mine and power station, and took their money elsewhere – having made huge profits and without agreeing to pay the full costs of rehabilitation. The Hazelwood cavity is still a huge fire risk and may become a toxic lake.

Doig’s book offers an acute critique of how governments cut environmental corners to sponsor mining and industry, about the civic and environmental irresponsibility of multinational mining corporations, and about why workers and communities dependent on such industries are often unwilling or unable to criticise them, until it is too late. Like Doig, I’m thinking Adani.

Comments powered by CComment