- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Custom Article Title: Daniel May reviews <em>Black Saturday: Not the end of the story</em> by Peg Fraser

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stories are at the heart of Peg Fraser’s compassionate and thoughtful book about Strathewen and the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires. The initial impression gained by the subtitle, Not the end of the story, could be one of defiance, a familiar narrative of a community stoically recovering and rebuilding ...

- Book 1 Title: Black Saturday

- Book 1 Subtitle: Not the end of the story

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 268 pp, 9781925523683

Each chapter starts with an object connected to the small Victorian settlement of Strathewen and the 2009 bushfires. All but one of these objects are now in Museum Victoria’s Bushfires Collection, which the author helped to curate. This literary technique allows Fraser to group her oral interviews and effectively frame her analysis of survivor testimony. Readers are introduced to Strathewen as a liminal place that does not fit easily into the city–country divide. This sets the tone for Fraser’s analysis, which questions many easy binaries and assumptions.

The strongest example of this questioning is the third chapter. Fraser tells how the Museum’s decision to exhibit a tree where some survivors posted poems of grief, community, and resilience provoked other survivors to object to the resilience narrative being promoted. Through interviews with the objecting survivors, Fraser demonstrates that the narrative of harmony and recovery concealed divisions and conflict present in Strathewen both before and after Black Saturday, and leads readers to question the implicit assumptions in dominant bushfire narratives. After reading this chapter, readers will find themselves questioning whether the word ‘community’ is a help or a hindrance in understanding disasters. Questioning the very concept of community may have intimidated a lesser writer, but it is a real strength of this book that Fraser does not flinch from uncomfortable truths and conflict. This commitment to truth over narrative simplicity is brave.

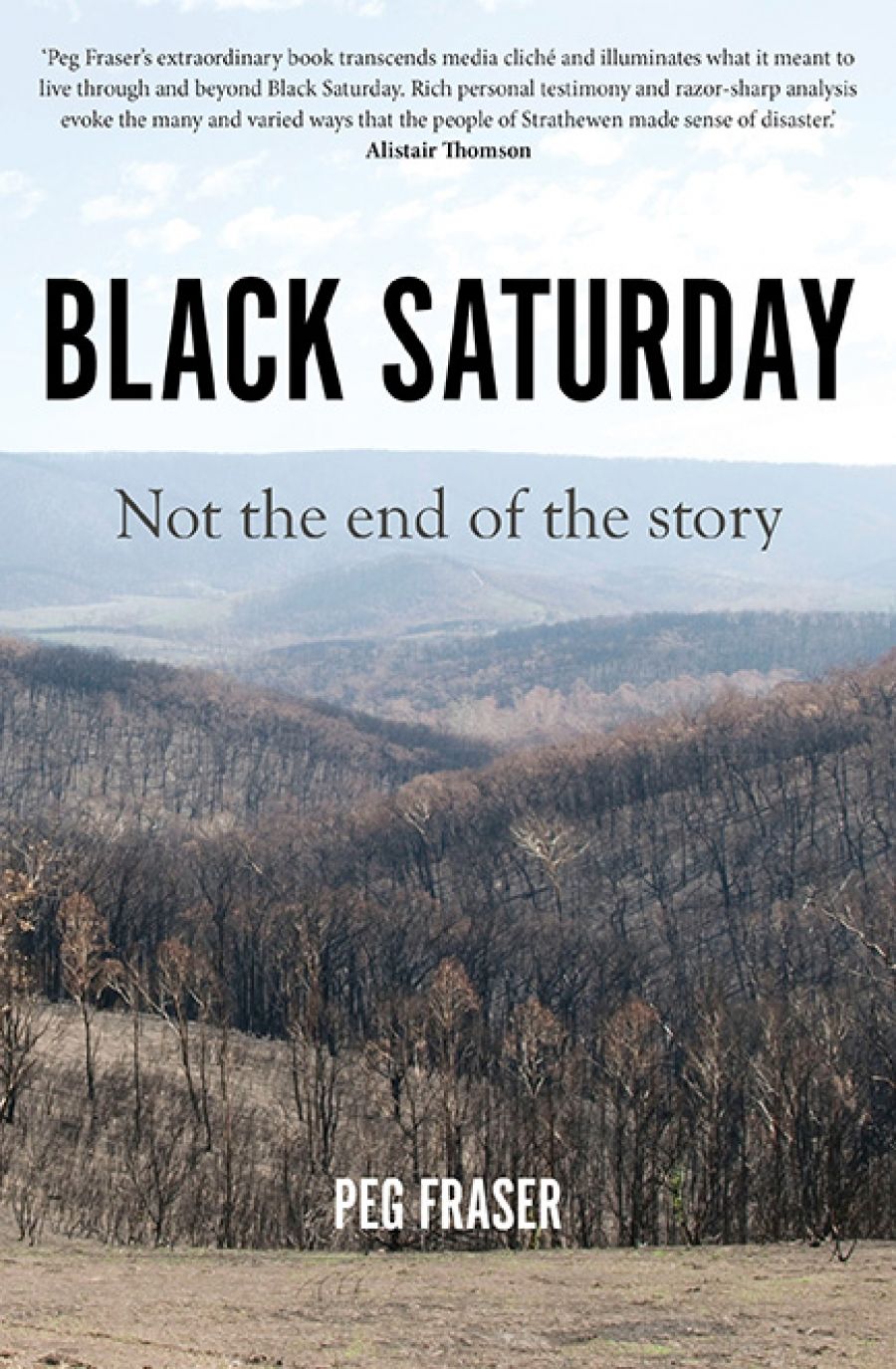

The Kinglake National Park after the Black Saturday bushfires (photograph by Nick Pitsas/CSIRO)

The Kinglake National Park after the Black Saturday bushfires (photograph by Nick Pitsas/CSIRO)

The sixth chapter uses a knitted cushion to explore how ideas and expectations around gender manifested during and after Black Saturday. When discussing objects, women mourned the loss of heirlooms and photographs, while men mourned the loss of their sheds. Actually, Fraser demonstrates that the loss of tools undermined the Australian male self-image as ‘practical, capable, self-reliant’; the loss of the shed meant ‘a failure to defend the home’.

A further highlight from this chapter is Fraser’s convincing argument that the much-maligned policy informally known as ‘stay or go’ was implicitly gendered in its framing, and that this had terrible consequences on 7 February 2009. Fraser found that some of her male interviewees who chose to evacuate have since struggled with feelings of inadequacy and of failing to live up to expectations of masculinity. Fraser further argues that the policy may well have led some to stay and attempt to defend their houses rather than ‘retreat’. Some of them may have died as a result. This gendered insight offers a new and insightful perspective. The arguments over ‘stay or go’ have tended to focus upon those who stayed behind, but Fraser reminds us that this policy also profoundly affected those who evacuated. This is a rare foray into policy debates, but it does not feel out of place and is a reminder of the power of good cultural research.

Black Saturday is not just for fire researchers, curators, and oral historians, but should also find a place on the shelf of anyone living in the ‘fire flume’ of Victoria. Unlike the impenetrably dense bureaucratic writing of officialdom, this book is easy to read. Better put perhaps, it makes a hard topic (or ‘difficult history’) more bearable. After all, Stretton’s enduring influence on the stories Australians tell about bushfire is at least in part due to his eloquence.

Stories help us to make sense of the world in the wake of disaster; they prompt us into action in the face of it. In this story about stories, Fraser complicates assumptions, teases out frameworks, and reminds us that the stories we tell ourselves after tragedies can conceal as much as they reveal.

Comments powered by CComment