- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

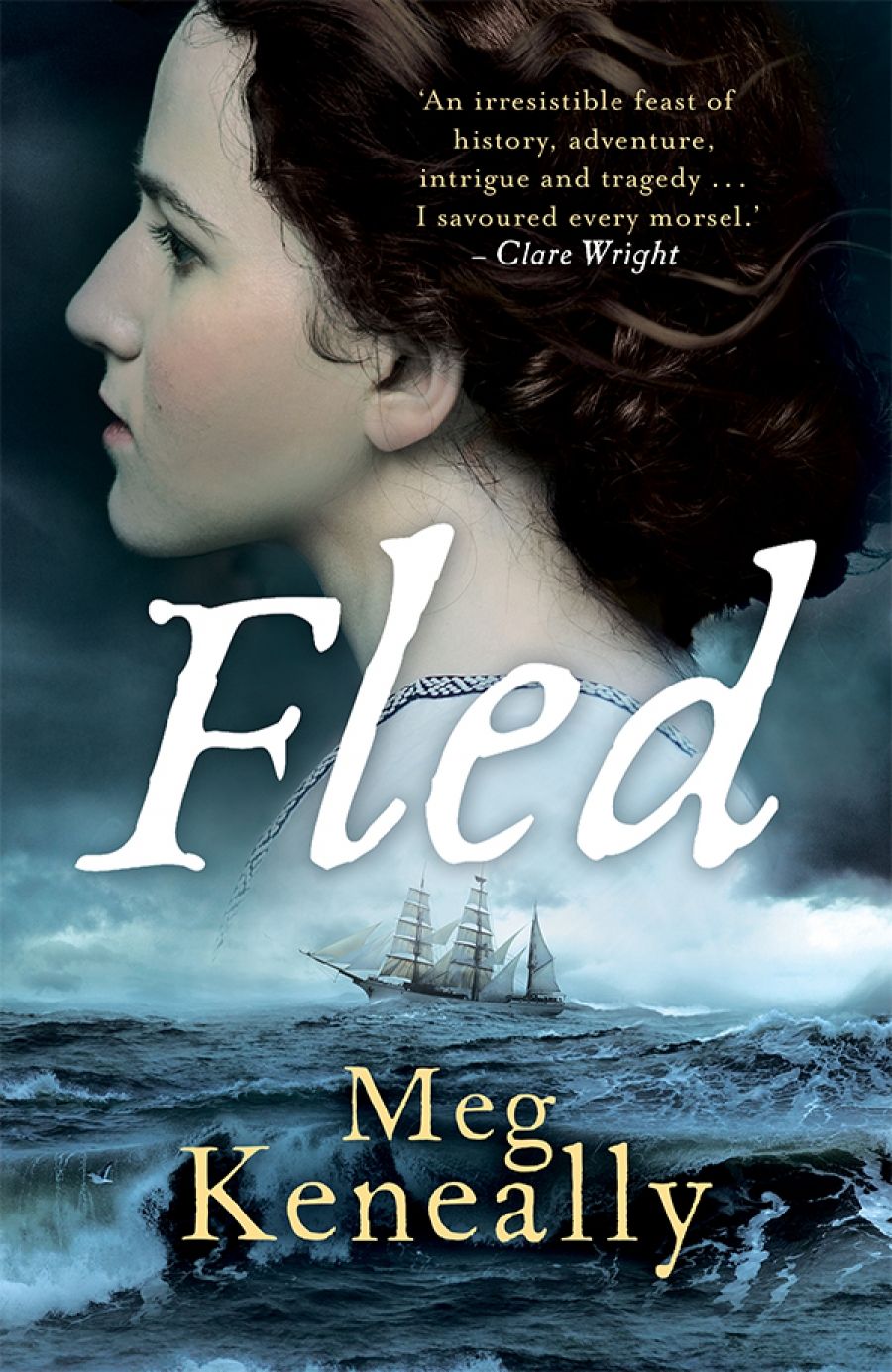

- Custom Article Title: Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews <em>Fled</em> by Meg Keneally

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1961 the great Australian poet Judith Wright published an influential essay called ‘The Upside-down Hut’ that would puzzle contemporary readers. The basis of its argument was that Australia felt shame about its convict origins, and that we needed to move on. And we have: since 1961 the representation of the convict era in fiction and on screen has ...

- Book 1 Title: Fled

- Book 1 Biblio: Echo Publishing, $29.99, 394 pp, 9781760680275

Keneally’s daughter Meg is no newcomer, either to fiction writing or to this historical subject matter and its moral and ethical dimensions. She has collaborated with her father on a series of co-written ‘convict crime’ novels: the Monsarrat Series features ex-con detective Hugh Monsarrat and his faithful housekeeper, Hannah Mulrooney, who embark on solving crimes in penal colonies, a different place for each book. Meg Keneally has been busy, for she and her father have produced a book a year in this series since 2016, with the latest published at the same time as this novel, her first solo effort. Fled is a fictionalised version of a true convict tale, featuring one of the toughest women in Australian history.

Mary Bryant, identified in the records as a ‘forest dweller’ and ‘highwaywoman’, and one of the few women of that era to score her own entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, was convicted of assault and robbery and was originally sentenced to hang, a sentence later commuted to seven years’ transportation. Arriving with the First Fleet, she made the best she could of conditions at Sydney Cove, acquiring a useful husband and a hut, but in 1791 she escaped the starving colony and, with the aid of advice and supplies from a Dutch sea captain, put out to sea in a small boat – audaciously stolen from Governor Arthur Phillip himself – with her husband, her two children, and nine other convicts. They were bound for the Dutch-held port of Kupang in West Timor, where Captain William Bligh and his companions had arrived two years earlier in an open boat, after the mutiny on the Bounty. This is by no means the end of her story; her life continued to be colourful and intermittently tragic.

Keneally distances her heroine a little from history, changing her name to Jenny Trelawney, tweaking the real-life plot here and there, and boldly inventing details of conversation and feeling that could only be guessed at. Many true stories sicken and die in the alien atmosphere of fiction, for life does not happen in the same shape as fiction or for the same reasons, but the original story is full of fascinating characters as well as dramatic and startling incidents, and Keneally’s perceptive and empathetic imagining of those characters is the best thing about this book.

She colours in and fleshes out the gaps where the stark historical record is silent. So we are given the action-packed story of how Jenny fell into a life of crime, some detailed backstory about her skill with boats that goes to explain the unlikely success of her escape, and a magnificent portrait of the colourful and eccentric James Boswell, biographer to Samuel Johnson, who, as a rich and influential citizen, really did take up Mary Bryant’s cause.

Meg and Tom Keneally (photograph via Penguin Random House)

Meg and Tom Keneally (photograph via Penguin Random House)

In particular, the treatment of Jenny’s relationships with men is done in a way that’s both realistic and sympathetic. She forges unions for pragmatic reasons, but there are a number of male characters – including Richard Aldred, the character based on Boswell – who like her simply for her intelligence and guts. It is she who pushes for marriage with the fisherman Daniel, a man she genuinely likes but also perceives as an asset. The delicate and intriguing way that Keneally develops the dynamics of this relationship, in all its shifting complexity, makes the plot’s dramatic turning point seem both terrible and inevitable.

Keneally also tackles the fraught notion of colonisation as invasion, and again her treatment of this subject is mostly complex and nuanced, though she may from time to time be idealising the relations between the Aboriginal people and the white invaders; in particular, it seems unlikely that relations between the women were as co-operative or as respectful as they are depicted here.

Like all good historical novels, this one has a message for the present: disruptive technologies create human tragedies. The reason why the English jails were overflowing in the 1770s was that the Industrial Revolution had put so many out of work, creating an underclass that was literally starving and had to steal to live in a society that offered them no help. In the twenty-first century, we are seeing the results of a technological revolution that has, again, put many out of work, and when such a situation is badly managed, the results are unpredictable and potentially dire. Keneally wisely does not spell this out, but it’s an idea that haunts the book.

Comments powered by CComment