- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Custom Article Title: Zora Simic </em>#MeToo: Stories from the Australian movement</em> edited by Natalie Kon-yu et al.

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

How do we get the measure of the phenomenon that is #MeToo? Both deeply personal and profoundly structural, #MeToo has been described as a movement, a moment, and a reckoning. Some critics have dismissed it as man-hating or anti-sex; sceptics as a misguided millennial distraction from more serious feminist concerns ...

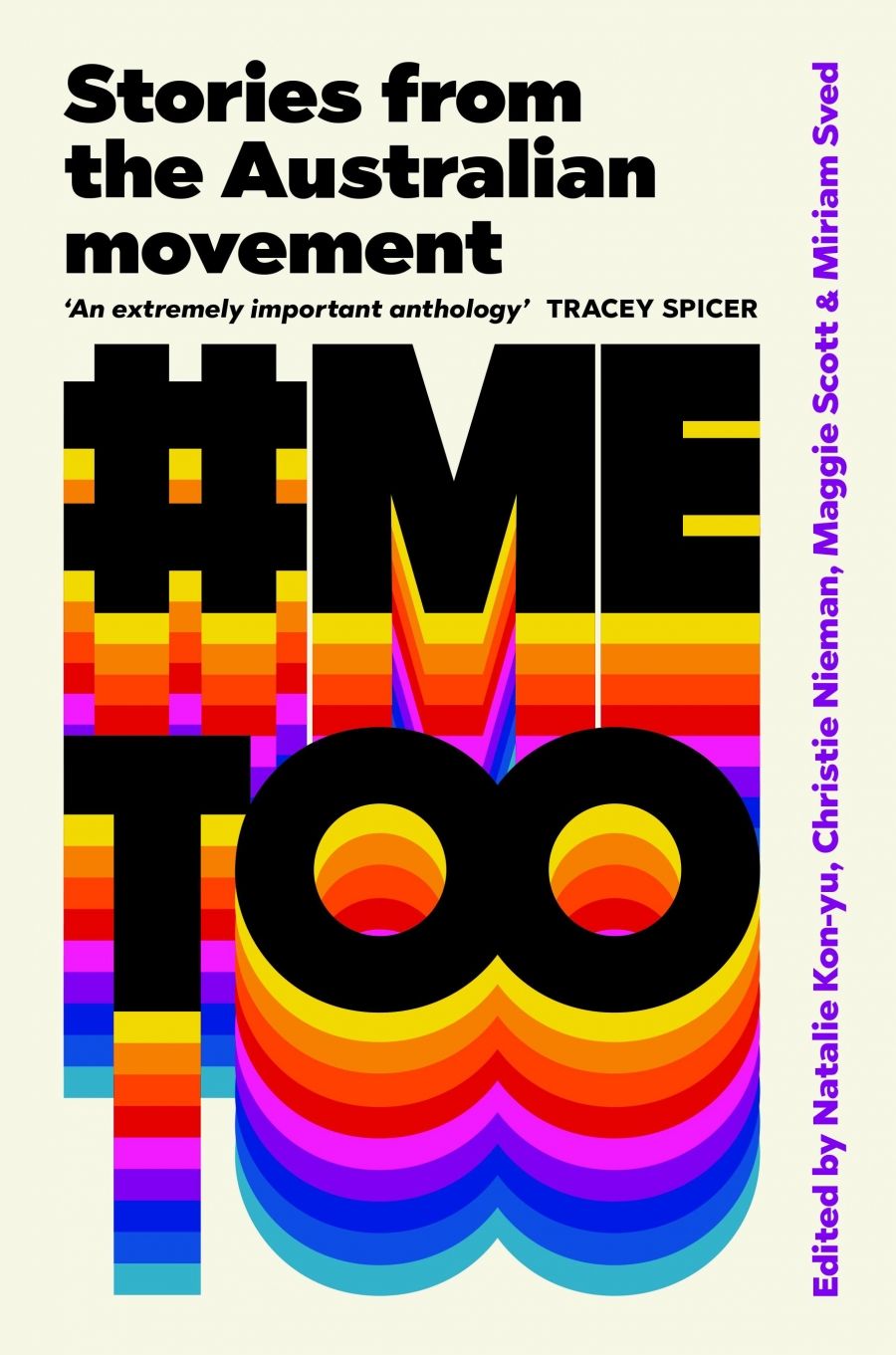

- Book 1 Title: #MeToo: Stories from the Australian movement

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $32.99 pb, 352 pp, 978176078500

The editors make no special plea as to why their collection is necessary, though there is a strong case to be made for a substantial text that counters the seemingly endless clickbait that continue to roll out with each new controversy. The value of stepping outside the news cycle to reflect on the deeper dimensions of #MeToo is potently demonstrated by the kaleidoscopic range of contributions. Apart from a couple of pieces by well-known journalists that, while engaging enough, largely rehash ideas published elsewhere, the selection of material manages to meet the challenge of genuine diversity of representation and views, as well as making for compelling reading.

Some of the most powerful contributions make no, or barely, any mention of #MeToo at all. Eugenia Flynn’s incantatory ‘This Place’ condemns ‘the white patriarchy that permeates all of the institutions of Australia’ from her particular vantage point as an Aboriginal woman. Given the ongoing history of ‘Black women speaking their truth as survivors of sexual assault, violence and abuse [and] … never being taken seriously’, she doubts #MeToo can carry or comprehend this weight. Instead, she draws strength from the ‘resistance of strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’.

Tarana Burke, founder of the #MeToo movement, in 2018 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Tarana Burke, founder of the #MeToo movement, in 2018 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

In an essay written in jaunty prose and with good humour, Maggie Scott shares some confronting family history about her much-missed maternal grandmother, who was affectionately known as Mammans. What Scott discovers deepens her understanding of Mammans, but also of herself and other women in her family. The experience and aftermath of abuse shapes a person and a family, but it’s a complicated legacy not easily reducible to tragedy – or a hashtag. The younger Scott women, she writes, have inherited ‘a bold look in the eye; a cutting sense of humour; a critical disposition towards men; and sororities of lifelong female friends’.

A similar spirit of resilience and reinvention animates Sylvie Leber’s extraordinary account of her own life since she was raped as a young woman in the early 1970s. Noting that she was possibly the first Australian woman to speak out in the media about having been raped, Leber’s contribution adds historical heft to the collection and is genuinely inspiring. Leber, unhappy with the way the mainstream media sensationalised her story, dedicated herself to remedying the problem of the lack of representation of women in Australian culture. She was a founder of the Melbourne Women’s Theatre Group, a member of the all-woman band Toxic Shock, and hosted a radio program called Give-Men-A-Pause. If she’s not already writing a memoir, I hope Leber is at least giving it some thought.

Leber’s life story testifies to the healing potential of speaking out about sexual violence, but other contributors are understandably more ambivalent. In her ruminative opening essay, Kath Kenny cites results from the last Global Media Monitoring Project which show that women make up less than a quarter of subjects interviewed or reported on, and that, when women do feature, they are most likely to be portrayed as victims or eyewitnesses rather than as experts. The implications for #MeToo are that, in this media environment, ‘speaking out as a victim makes it next to impossible to speak out as an expert’. To counter the reductive stereotypes and lack of complexity in media coverage, Kenny turns to feminist thinkers alert to the grey areas, including of course – given this is an Australian collection – Helen Garner.

For Eleanor Jackson, an invitation to have a public conversation with Germaine Greer about her treatise On Rape invites reflection on the value of such an exchange. Jackson ultimately declined the invitation. In writing about why she did, she offers a more nuanced and memorable discussion of the issues at hand than such an event would have permitted. As does Shakira Hussein’s perceptive analysis of what she calls the ‘uneven distribution of trauma’ borne by women from the most vulnerable and marginalised communities. #MeToo, she writes, was ‘supposed to be the revolution I was waiting for – yet I was left feeling isolated rather than connected, helpless rather than empowered’. Reflecting on the tragic case of Afghani teenager Ziba Haji Zada, who was found with fatal burns in her in-law’s Melbourne backyard in early 2018, soon after #MeToo went viral, Hussein persuasively argues that ‘much more is needed than obligatory storytelling and the downfall of a cluster of high-profile offenders’.

Along with Hussein, several other contributors draw necessary attention to under-resourced services, deficient policing, and a hostile legal system. The music, theatre, and sports industries each come under scrutiny. Cultural and institutional change is a hard slog; we know this, and for this reason I’ll end with hopeful suggestions and developments raised by spokespeople from female-dominated professions in which sexual harassment and abuse is endemic. Victorian MP and sex worker advocate Fiona Patten encourages more talk about sexual pleasure and would welcome, in her Twitter feed, a tweet reading ‘I had great sex last night. #MeToo’. Meanwhile, nurse educator Simone Sheridan celebrates #MeToo as a genuine catalyst for nurses to speak out about what was previously brushed aside or left unspoken. She says plainly, ‘Australian nurses are being sexually harassed by our patients. And it’s not part of our job.’ That this needs iterating is but one of many examples why #MeToo does matter, and why #MeToo: Stories from the Australian Movement should be essential reading for anyone with an interest in positively transforming our workplaces, relationships, and wider culture.

Comments powered by CComment