ABR has asked fourteen academics to respond to revelations that Education Minister Simon Birmingham had vetoed eleven Australian Research Council grants despite the Australian Research Council’s rigorous peer-review process. 'The humanities are the heart of our culture and of our knowledge,' writes Philip Mead in his response, 'and their relevance is a constant source of surprise and sustenance – giving us answers to questions we hardly knew to ask.’ One wonders if Professor Mead’s view is shared by the federal government. Not for the first time, it has targeted the humanities in a way that does not apply to science or technology. ABR shares the academic community’s dismay at this philistine assault on academic freedom.

Margaret Gardner

Professor Margaret Gardner (photograph via Monash University)At Senate Estimates on 25 October 2018, it was revealed that eleven ARC grants for 2017 were rejected by the then Education Minister, Simon Birmingham. It has been many years since a Minister decided to override the exhaustive peer-review process. The Minister, with no explanation, rejected more than $4 million of grants to the humanities. Until the Senate Estimates revelation, those researchers believed that, despite receiving positive reviewer reports, they had just failed to make the cut. Now we all know they had made the cut, against fierce competition from the best researchers in their fields in the nation. But the Minister didn’t approve the awards. Not only were his decisions kept secret, there was no accounting for the reasons – apart from the views he revealed on Twitter when this information became public.

Professor Margaret Gardner (photograph via Monash University)At Senate Estimates on 25 October 2018, it was revealed that eleven ARC grants for 2017 were rejected by the then Education Minister, Simon Birmingham. It has been many years since a Minister decided to override the exhaustive peer-review process. The Minister, with no explanation, rejected more than $4 million of grants to the humanities. Until the Senate Estimates revelation, those researchers believed that, despite receiving positive reviewer reports, they had just failed to make the cut. Now we all know they had made the cut, against fierce competition from the best researchers in their fields in the nation. But the Minister didn’t approve the awards. Not only were his decisions kept secret, there was no accounting for the reasons – apart from the views he revealed on Twitter when this information became public.

This is a fundamental affront to the principles on which universities operate. Academic or intellectual freedom guarantees the pursuit of knowledge free of interference or repression by external and internal parties. We, as universities, guarantee this freedom within their areas of expertise to our staff through statute and regulation. To see this core principle so cavalierly undermined is profoundly worrying. The Minister is, in his role, allocating research funding, on advice, to support the research mission of universities. The discretion he exercises should not be a personal one, based on his limited opinions about research topics.

When individuals seek to undermine the nature of our collective academic endeavour, we must protest. In Minister Birmingham’s secret and ill-conceived derogation of humanities research and researchers, we have reached such a point. We have values to be defend. We demand that these actions not be repeated. We must not let this matter be brushed aside.

Professor Margaret Gardner AO is President and Vice-Chancellor of Monash University and Chair of Universities Australia

Ian Donaldson

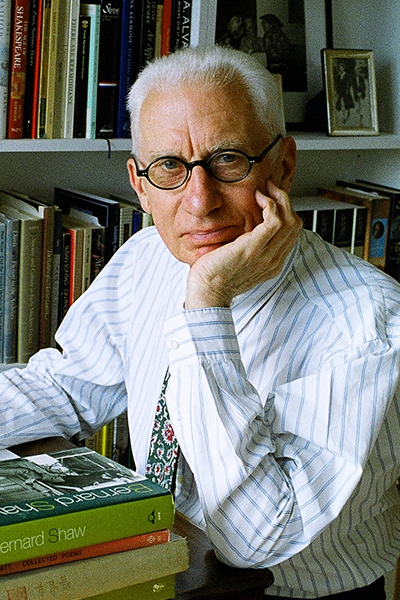

Professor Ian Donaldson (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Once in office, no federal Minister of Education – however diverse and distinguished their own educational record may have been – has the time, the up-to-date knowledge, or the multiple skills required to assess the many applications for government funding over which they exercise nominal oversight. Happily, the Minister is always helped in this task by the detailed assessments of experts, commissioned from within Australia and across the world, who are asked to judge whether grant proposals are, or are not, of outstanding significance and worthy of public support. There may be occasions when a Minister sees what an expert in the field has failed to see: that a research proposal is in some way mischievous, ill conceived, or damaging to the national interest. On such rare occasions, the Minister must clearly explain to the researchers themselves, to their expert assessors, and to the general public the reasons for vetoing an already recommended grant. To withhold such an explanation – more astonishingly, to suppress all public knowledge of their veto – is to act not as an animator and inspirer of national research, but as a faceless bureaucrat might act in the service of a totalitarian state. Australia can do much better than that.

Professor Ian Donaldson (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Once in office, no federal Minister of Education – however diverse and distinguished their own educational record may have been – has the time, the up-to-date knowledge, or the multiple skills required to assess the many applications for government funding over which they exercise nominal oversight. Happily, the Minister is always helped in this task by the detailed assessments of experts, commissioned from within Australia and across the world, who are asked to judge whether grant proposals are, or are not, of outstanding significance and worthy of public support. There may be occasions when a Minister sees what an expert in the field has failed to see: that a research proposal is in some way mischievous, ill conceived, or damaging to the national interest. On such rare occasions, the Minister must clearly explain to the researchers themselves, to their expert assessors, and to the general public the reasons for vetoing an already recommended grant. To withhold such an explanation – more astonishingly, to suppress all public knowledge of their veto – is to act not as an animator and inspirer of national research, but as a faceless bureaucrat might act in the service of a totalitarian state. Australia can do much better than that.

Professor Ian Donaldson FAHA, FBA, FRSE, Emeritus Professor at ANU and Honorary Professorial Fellow, School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne

Brian Schmidt

Professor Brian Schmidt (photograph via ANU)We learned recently that eleven humanities ARC grants that had been recommended for funding through the peer-review process were denied by the former Education Minister Simon Birmingham. These included an early career fellowship (DECRA) for one of our own staff members, Dr Robert Wellington. I have committed the University to provide support so that Robert is able to maintain his research program.

Professor Brian Schmidt (photograph via ANU)We learned recently that eleven humanities ARC grants that had been recommended for funding through the peer-review process were denied by the former Education Minister Simon Birmingham. These included an early career fellowship (DECRA) for one of our own staff members, Dr Robert Wellington. I have committed the University to provide support so that Robert is able to maintain his research program.

Universities’ power to speak truth comes through their integrity, which is underpinned by the principles of academic freedom and academic autonomy. Within Western democracies, governments support these principles by providing research grants, typically administered by independent agencies, that are judged by a peer-review process, free of political or other types of interference. The competitive grants programs play a vital role in Australia’s research landscape, so it is essential that trust and confidence in their integrity are restored.

I am proud that ANU stands as one of the world’s strongest centres of humanities research. The outcomes of research in these disciplines are integral to understanding and tackling many of the big issues facing society, and I affirm the commitment of ANU to humanities research as a core activity. ANU joins the broader university sector in condemning the undermining of our peer-reviewed grant system. We will continue to advocate for humanities research to receive appropriate funding, free from political interference.

Professor Brian P. Schmidt AC FAA, FRS, Vice-Chancellor, President and Chief Executive Officer of ANU, Nobel Laureate in Physics, 2011

André Brett

Dr André Brett (photograph via Melbourne University Publishing)The effects of Simon Birmingham’s intervention for early career researchers (ECRs) are especially chilling. One victim of this veto consequently moved his young family to the United Kingdom because he could not obtain a position in Australia. ECRs represent some of Australia’s most promising and insightful new talent, yet little is done to keep them in our universities, where casualisation and precariousness are the norm. ARC grants are often make-or-break because chronic failures at institutional, system, and government levels have made stable, full-time academic positions elusive, especially in the humanities. To add a secret veto is injurious; to exercise it on a cursory glance at titles adds insult to injury; to defend the veto with flippant tweets is to rub salt into the wound. It is hard to view Birmingham’s behaviour as that of somebody serious about research excellence – or somebody serious about treating others professionally and respectfully. And if Dan Tehan is so concerned with research in the ‘national interest’, perhaps some enterprising researchers should pitch a project to examine whether national interest tests are in fact in the national interest. It is obviously not in the national interest to lose talented minds.

Dr André Brett (photograph via Melbourne University Publishing)The effects of Simon Birmingham’s intervention for early career researchers (ECRs) are especially chilling. One victim of this veto consequently moved his young family to the United Kingdom because he could not obtain a position in Australia. ECRs represent some of Australia’s most promising and insightful new talent, yet little is done to keep them in our universities, where casualisation and precariousness are the norm. ARC grants are often make-or-break because chronic failures at institutional, system, and government levels have made stable, full-time academic positions elusive, especially in the humanities. To add a secret veto is injurious; to exercise it on a cursory glance at titles adds insult to injury; to defend the veto with flippant tweets is to rub salt into the wound. It is hard to view Birmingham’s behaviour as that of somebody serious about research excellence – or somebody serious about treating others professionally and respectfully. And if Dan Tehan is so concerned with research in the ‘national interest’, perhaps some enterprising researchers should pitch a project to examine whether national interest tests are in fact in the national interest. It is obviously not in the national interest to lose talented minds.

Dr André Brett, Postdoctoral research fellow in History, University of Wollongong

Stephen Garton

Professor Stephen Garton (photograph via University of Sydney)One of the many troubling aspects of the Seantor Birmingham’s egregious and deeply politicised action, is less the assertion that expertise can be trumped by politics (after all, it has happened before), but that this appeal to the mythical ‘base’ barely stirred the political waters. That suggests something disconcerting about the broader public perception of universities. It is fascinating that what is supposedly happening in the humanities and social sciences looms so large in the popular imaginary of what a university is. On the other hand, that popular imaginary is dispiriting given that it is so far removed from reality. The accusation that all ‘we’ do is ‘identity politics’ is deeply ingrained in many quarters. People look at me in amazement when I tell them that the most popular undergraduate major at Sydney is Economics. What would happen, however, if ministerial interference came to impact research on climate change? Would this rouse a greater popular outcry? I suspect so, but that in itself suggests that we haven’t yet persuaded sufficient numbers of citizens of the value of the humanities, despite years of good and purposeful activity to this end. We have culture work still to do.

Professor Stephen Garton (photograph via University of Sydney)One of the many troubling aspects of the Seantor Birmingham’s egregious and deeply politicised action, is less the assertion that expertise can be trumped by politics (after all, it has happened before), but that this appeal to the mythical ‘base’ barely stirred the political waters. That suggests something disconcerting about the broader public perception of universities. It is fascinating that what is supposedly happening in the humanities and social sciences looms so large in the popular imaginary of what a university is. On the other hand, that popular imaginary is dispiriting given that it is so far removed from reality. The accusation that all ‘we’ do is ‘identity politics’ is deeply ingrained in many quarters. People look at me in amazement when I tell them that the most popular undergraduate major at Sydney is Economics. What would happen, however, if ministerial interference came to impact research on climate change? Would this rouse a greater popular outcry? I suspect so, but that in itself suggests that we haven’t yet persuaded sufficient numbers of citizens of the value of the humanities, despite years of good and purposeful activity to this end. We have culture work still to do.

Professor Stephen Garton FAHA, FASSA, FRAHS, Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor, The University of Sydney

Catherine Kevin

Dr Catherine Kevin (photograph via Flinders University)Simon Birmingham has interfered in the granting of research funds on the grounds of a notional taxpayer who is apparently unaware of how specialised knowledge-building works and the context in which it takes place. The international context is crucial for universities in more ways than one. Part of the remit of research is to illuminate Australia’s relevance to the world, to ensure that our experiences, concerns, and expertise are integrated into global conversations, that the connections are made. More pragmatically, international research impact is a key measure in all three major university ranking systems, and these are closely linked to the global education market. International students are buyers in the global marketplace and for them rankings count. If researchers are forced to tailor their proposals to Birmingham’s parochial, short-term interests, their universities will be hampered in this market and in the global conversation.

Dr Catherine Kevin (photograph via Flinders University)Simon Birmingham has interfered in the granting of research funds on the grounds of a notional taxpayer who is apparently unaware of how specialised knowledge-building works and the context in which it takes place. The international context is crucial for universities in more ways than one. Part of the remit of research is to illuminate Australia’s relevance to the world, to ensure that our experiences, concerns, and expertise are integrated into global conversations, that the connections are made. More pragmatically, international research impact is a key measure in all three major university ranking systems, and these are closely linked to the global education market. International students are buyers in the global marketplace and for them rankings count. If researchers are forced to tailor their proposals to Birmingham’s parochial, short-term interests, their universities will be hampered in this market and in the global conversation.

It is ironic that federal governments have increased pressure on universities to rely on international student income. Given Birmingham’s dismissal of ARC applications on the basis of their titles, is it any surprise that someone is failing to join the dots in the government’s flawed approach?

Dr Catherine Kevin, Senior Lecturer in Australian History, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University

Tom Griffiths

Professor Tom Griffiths (photograph via ANU)Simon Birmingham interfered in an independent review process, failed to understand the gravity of his personal intervention, and mocked the research being proposed. As Minister, he is not the expert on individual research projects. He is there to support the independent ARC, not to undermine its procedures. Decisions about research quality are not matters for politicians. The current peer-review assessment process is rigorous, exhausting, and punishing enough, and the opportunity costs of applying are, I believe, already too high. The Australian summer, which is a scholar’s precious, seasonal window of creativity, is now sacrificed to grant-writing. The impact of such summers on university research culture and morale is dire. If the Minister now imposes a further political veto, then the whole process is insupportable.

Professor Tom Griffiths (photograph via ANU)Simon Birmingham interfered in an independent review process, failed to understand the gravity of his personal intervention, and mocked the research being proposed. As Minister, he is not the expert on individual research projects. He is there to support the independent ARC, not to undermine its procedures. Decisions about research quality are not matters for politicians. The current peer-review assessment process is rigorous, exhausting, and punishing enough, and the opportunity costs of applying are, I believe, already too high. The Australian summer, which is a scholar’s precious, seasonal window of creativity, is now sacrificed to grant-writing. The impact of such summers on university research culture and morale is dire. If the Minister now imposes a further political veto, then the whole process is insupportable.

Professor Tom Griffiths AO FAHA, Emeritus Professor, ANU

Lisa Featherstone

Associate Professor Lisa Featherstone (photograph via The University of Queensland)In 2017, Australia’s third-largest export earner was the higher education of international students, beaten only by iron ore and coal. Higher education is the largest service industry, well ahead of income brought in from tourism. Despite cuts to the sector, Australia’s higher education sector is strong, and many Australian universities score highly on prestigious international scales. These scales are developed largely on research quality and quantity (rather than teaching), yet they are a major factor in attracting both undergraduate and postgraduate students from across the globe.

Associate Professor Lisa Featherstone (photograph via The University of Queensland)In 2017, Australia’s third-largest export earner was the higher education of international students, beaten only by iron ore and coal. Higher education is the largest service industry, well ahead of income brought in from tourism. Despite cuts to the sector, Australia’s higher education sector is strong, and many Australian universities score highly on prestigious international scales. These scales are developed largely on research quality and quantity (rather than teaching), yet they are a major factor in attracting both undergraduate and postgraduate students from across the globe.

Australian universities have flourishing research cultures. Research cultures require funding, and the Australian Research Council is central to this, especially in the humanities, where grants are both scarce and highly regarded. The recent ministerial interference is troubling on many grounds. If we want high-profile researchers who can perform on the international stage, we need to allow researchers to follow their passions, and to develop new knowledge across all of the humanities, to be shared with our students and the broader community. More pragmatically, lack of funding will lead inevitably to falling rankings of Australian universities on international scales. In the longer term, this will no doubt lead to lower numbers of fee-paying students.

The impact of the minister’s interference is profound, with repercussions that are already reverberating through the sector.

Associate Professor Lisa Featherstone, Director of Teaching and Learning, School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, The University of Queensland

Philip Mead

Professor Philip Mead (photograph via University of Melbourne)What has Australia lost with Minister Birmingham’s intervention into national research funding? How is our research culture poorer? And our contribution to world knowledge diminished? We’ve lost the investigative thinking of six established scholars about important contemporary social upheavals like rioting, and its links across the United Kingdom, America, Australia, and the Middle East. One of Australia’s leading art historians and his ideas about orientalist scholarship and the Mediterranean have been rubbished. We’ve lost the excitingly innovative work of three young scholars, including an original contribution to the history of film in a project about the relation of soviet cinema to Hollywood filmmaking. The brilliantly forward-looking work of one scholar about musicology and birdsong, and another’s about the struggle of First Nations peoples with modernity have been turned down.

Professor Philip Mead (photograph via University of Melbourne)What has Australia lost with Minister Birmingham’s intervention into national research funding? How is our research culture poorer? And our contribution to world knowledge diminished? We’ve lost the investigative thinking of six established scholars about important contemporary social upheavals like rioting, and its links across the United Kingdom, America, Australia, and the Middle East. One of Australia’s leading art historians and his ideas about orientalist scholarship and the Mediterranean have been rubbished. We’ve lost the excitingly innovative work of three young scholars, including an original contribution to the history of film in a project about the relation of soviet cinema to Hollywood filmmaking. The brilliantly forward-looking work of one scholar about musicology and birdsong, and another’s about the struggle of First Nations peoples with modernity have been turned down.

The humanities are the heart of our culture and of our knowledge, and their relevance is a constant source of surprise and sustenance – giving us answers to questions we hardly knew to ask. Australian taxpayers will be dismayed to see the value of our humanities research disrespected and its global impact reduced. They will also be distressed by the effects of this intervention on our winning researchers.

Professor Philip Mead FAHA, Professor Emeritus of Australian Literature, University of Western Australia, Honorary Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne, ARC College of Experts

Margaret Harris

Professor Margaret Harris (photograph via University of Sydney)For at least twenty-five years I have heard speculation about the ARC and its alleged preferences and prejudices. Yet even the most vociferous doubters, when put to the test of service on a selection panel, have declared the ARC’s processes to be as fair as humanly possible. The Minister’s decision to reject the expert advice that generated eleven of the ARC’s recommendations demonstrates contempt both for the proposed projects and the rigorous process of assessment undertaken without payment by humanities and creative arts academics and practitioners. Assessors, whether national or international, have had their confidence in the integrity of the process in which they participate completely undermined by arrogant political censorship. Would the minister have applied what for all the world seems like a version of the pub test to grants from science or technology disciplines?

Professor Margaret Harris (photograph via University of Sydney)For at least twenty-five years I have heard speculation about the ARC and its alleged preferences and prejudices. Yet even the most vociferous doubters, when put to the test of service on a selection panel, have declared the ARC’s processes to be as fair as humanly possible. The Minister’s decision to reject the expert advice that generated eleven of the ARC’s recommendations demonstrates contempt both for the proposed projects and the rigorous process of assessment undertaken without payment by humanities and creative arts academics and practitioners. Assessors, whether national or international, have had their confidence in the integrity of the process in which they participate completely undermined by arrogant political censorship. Would the minister have applied what for all the world seems like a version of the pub test to grants from science or technology disciplines?

Margaret Harris FAHA, Challis Professor of English Literature Emerita, The University of Sydney

Mark Edele

Professor Mark Edele (photograph via University of Melbourne)I agree with the minister. Taxpayer dollars should be spent in the national interest. However, ‘national benefit’ is already part of the application process. So, either the change is semantic or what we are really talking about is a pub test. The outcome would depend on the drinking establishment in question. In my local in the inner north of Melbourne, for example, being a historian of the Soviet Union regularly passes muster. I would happily present my proposals there.

Professor Mark Edele (photograph via University of Melbourne)I agree with the minister. Taxpayer dollars should be spent in the national interest. However, ‘national benefit’ is already part of the application process. So, either the change is semantic or what we are really talking about is a pub test. The outcome would depend on the drinking establishment in question. In my local in the inner north of Melbourne, for example, being a historian of the Soviet Union regularly passes muster. I would happily present my proposals there.

Why not instead shut down the ARC? Distribute the money back to the Universities to be used for Humanities research and teaching. Then, Australian academics would no longer have to spend a quarter of their year on impossibly complex applications and their peer review. The best scholars would no longer be shut away in an ivory tower to write more proposals, never to see a student again. Careers would again be dependent on excellence in scholarship and teaching rather than in grant success. Professors would share the teaching with lecturers. Junior academics, no longer groaning under impossible teaching loads and insecure employment, could also write smart books. Now that would truly be in the national interest.

Professor Mark Edele, Hansen Chair in History, The University of Melbourne; ARC Future Fellow; Member of the ARC College of Experts

Kate Fullagar

Dr Kate Fullagar (photograph via Twitter)In the ongoing furore around revelations of ministerial research grant vetoes, two things are in danger of slipping from view. One is that the vetoes always and only target the humanities. The other is that the government is now gaslighting the public about what went on. In the ludicrous debate about pub tests, no one holds up non-humanities titles for scrutiny. A random search for recently funded STEM grants turns up ‘Noncommutative geometry in representation theory and quantum physics’, ‘Structure-activity relationships in silicon-based photovoltaics through atomic scale microscopy’, and ‘Multi-person stochastic games with idiosyncratic information flows’. I do not know what any of these mean. But that is the point. I need experts to tell me what they are about, why they should be funded, and what they could do for knowledge, humanity, or the planet. If they got funded by the ARC, I trust that they are worthy because I know they were scrutinised by around ten people at the university level before even being submitted, and that they were then reviewed by two to six anonymous peers before passing an analysis by a College of internationally recognised scholars. The government needs to explain its methodology and objective in applying one test for some and a second for others.

Dr Kate Fullagar (photograph via Twitter)In the ongoing furore around revelations of ministerial research grant vetoes, two things are in danger of slipping from view. One is that the vetoes always and only target the humanities. The other is that the government is now gaslighting the public about what went on. In the ludicrous debate about pub tests, no one holds up non-humanities titles for scrutiny. A random search for recently funded STEM grants turns up ‘Noncommutative geometry in representation theory and quantum physics’, ‘Structure-activity relationships in silicon-based photovoltaics through atomic scale microscopy’, and ‘Multi-person stochastic games with idiosyncratic information flows’. I do not know what any of these mean. But that is the point. I need experts to tell me what they are about, why they should be funded, and what they could do for knowledge, humanity, or the planet. If they got funded by the ARC, I trust that they are worthy because I know they were scrutinised by around ten people at the university level before even being submitted, and that they were then reviewed by two to six anonymous peers before passing an analysis by a College of internationally recognised scholars. The government needs to explain its methodology and objective in applying one test for some and a second for others.

Minister Tehan recently claimed to adjust the rules for future ARC grants in order to ‘improve the public’s confidence’ in the grant system. His predecessor, however, gave no evidence of feeling pressure from the public and vetoed titles that had not been seen by the public. After such a flagrant dismissal of expert advice, it is the ministry that needs to regain our confidence.

Dr Kate Fullagar, Senior Lecturer, Department of Modern History, Politics and International Relations, Macquarie University

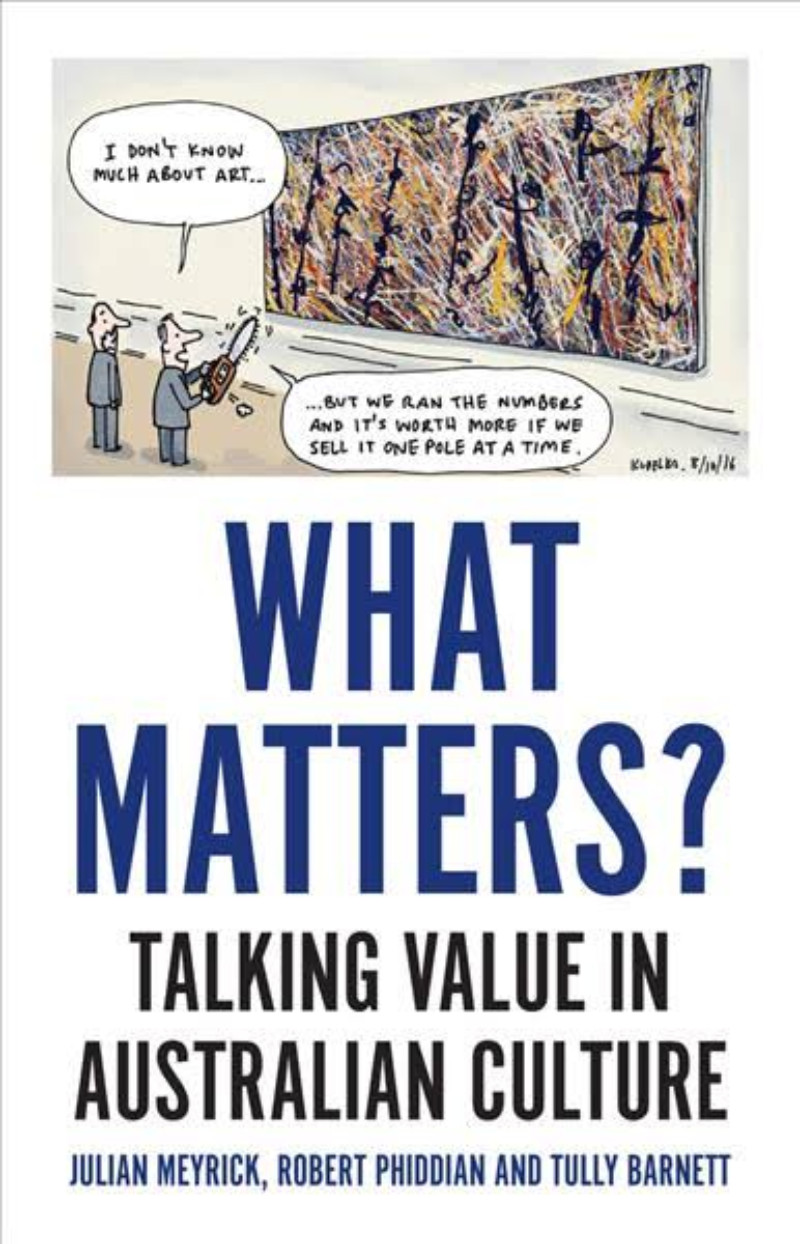

Robert Phiddian

Professor Robert Phiddian (photograph via Flinders University)Yet again our sector is a victim of its low fiscal stakes and high symbolic value. It was the arts and Brandis in 2015; now it’s Birmingham and the humanities in 2018. The culture warriors make a virtue-signalling racket, knowing that the lives and careers of people in culture can be messed with casually and at no real financial or political cost. No real financial cost: $200,000 for a research project is a lot of money for an individual, but the arbitrarily condemned projects don’t amount even to a rounding error in the context of a federal budget. No real political costs: humanities and the arts have for decades been lost to the conservatives. But real institutional cost: playing to the peanut gallery to subvert settled scholarly and bureaucratic processes (never perfect, but better than decision by populist whim) is the current fad, with everything reduced to tactical political advantage.

Professor Robert Phiddian (photograph via Flinders University)Yet again our sector is a victim of its low fiscal stakes and high symbolic value. It was the arts and Brandis in 2015; now it’s Birmingham and the humanities in 2018. The culture warriors make a virtue-signalling racket, knowing that the lives and careers of people in culture can be messed with casually and at no real financial or political cost. No real financial cost: $200,000 for a research project is a lot of money for an individual, but the arbitrarily condemned projects don’t amount even to a rounding error in the context of a federal budget. No real political costs: humanities and the arts have for decades been lost to the conservatives. But real institutional cost: playing to the peanut gallery to subvert settled scholarly and bureaucratic processes (never perfect, but better than decision by populist whim) is the current fad, with everything reduced to tactical political advantage.

Not many dead in this little skirmish, perhaps, but where to next when a future Minister Humpty Dumpty can declare that national interest ‘means just what I choose it to mean’? It’s a very bad decision – even worse as a precedent.

Robert Phiddian, Professor of English at Flinders University, foundation director of the Australasian Consortium of Humanities Research Centres (2011–17)

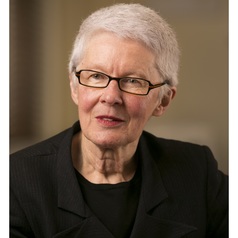

Professor Marilyn Lake (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Marilyn Lake

Professor Marilyn Lake (photograph via the University of Melbourne)Marilyn Lake

Historians must attend to context. Even as the Coalition government intervened to veto ARC grants for young scholars in the humanities – eleven of the small minority of applications approved through an extensive independent review process – and insists on maintaining funding cuts to our major cultural institutions, including the Australian National Library and National Archives, it offers an astonishing $500 million dollars to the Australian War Memorial so that it might expand exhibitions of the nation’s military history. With its new insistence on research that serves Australia’s security, foreign policy, and strategic national interests (The Age, 11 November 2018), the Coalition government makes explicit its support for the militarisation of our history and culture at the expense of original scholarship of international significance. Border-force mentalities now police the nation’s intellectual work even as they preside over customs, immigration, and the turn-back of asylum seekers.

Marilyn Lake AO DLitt FAHA FASSA is Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Research for her next book, Progressive New World: How settler colonialism and transpacific exchange shaped American reform, forthcoming with Harvard University Press, was supported by an ARC Discovery grant.

Enjoy ABR? Follow us:

(A tick means you already do)

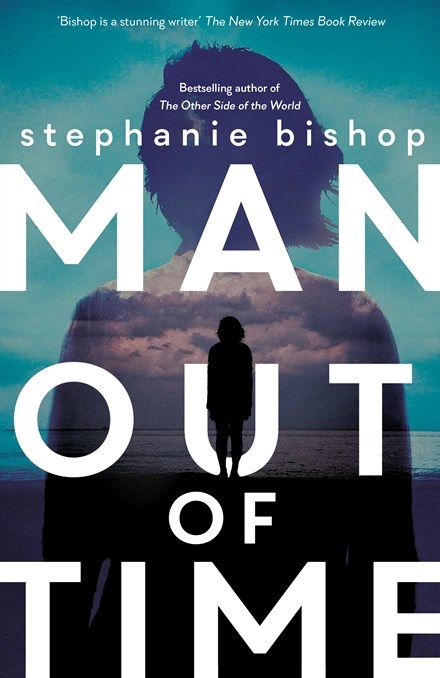

Man out of Time by Stephanie BishopStephanie Bishop’s remarkable novel Man Out of Time (Hachette, reviewed in ABR 9/18) explores a man’s breakdown and its effects on his family. It’s shimmering and sorrowful, and the writing is extraordinary. Too Much Lip (UQP, 10/18) by Melissa Lucashenko is a strong, unflinching novel about homecoming and history. With trademark wit and lucidity, Lucashenko connects the lives of her sharply drawn characters to a dysfunctional national story. Enza Gandolfo’s The Bridge (Scribe, 5/18), set among working-class lives, considers the collapse of the Westgate Bridge alongside a contemporary tragedy. It’s a moving, unsentimental novel about ethical complexities. Ghachar Ghochar (Faber, 2015) is a disturbing novella by Vivek Shanbhag (translated by Srinath Perur) about an Indian family that becomes wealthy – a gem.

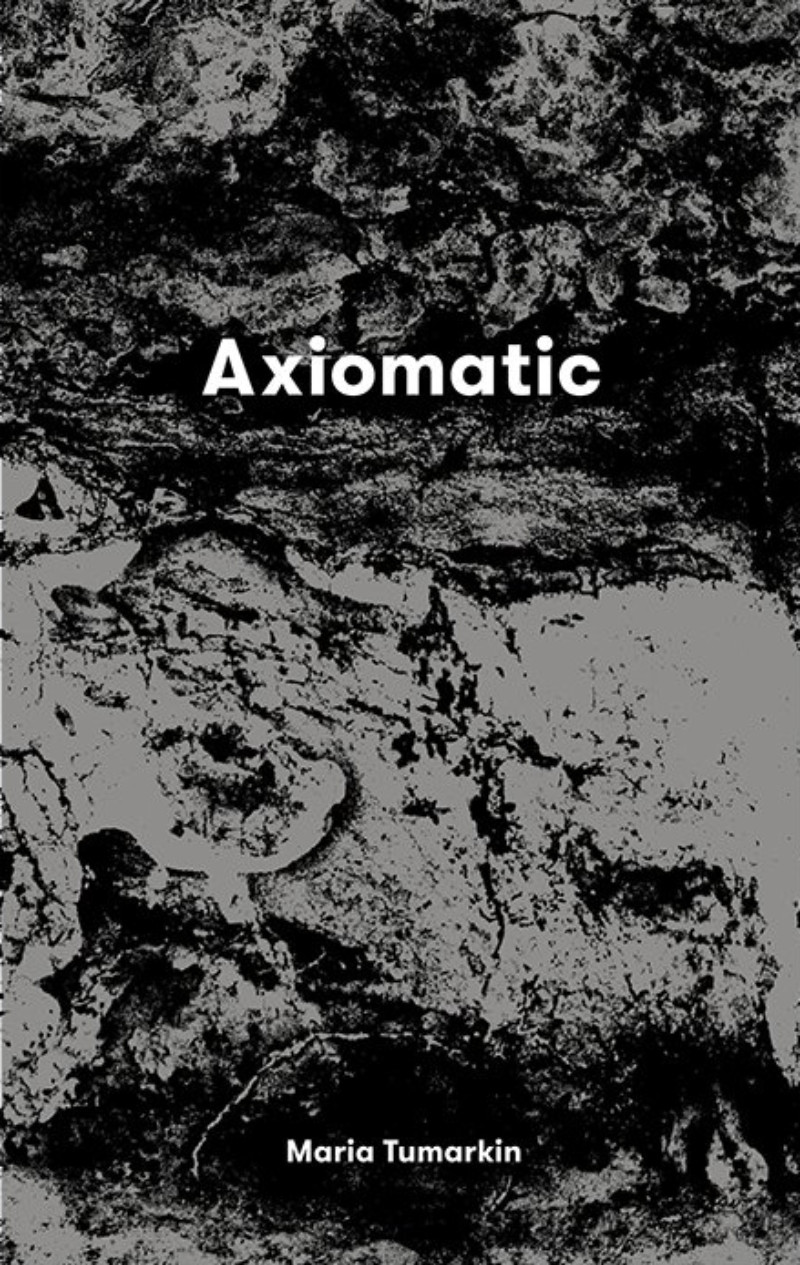

Man out of Time by Stephanie BishopStephanie Bishop’s remarkable novel Man Out of Time (Hachette, reviewed in ABR 9/18) explores a man’s breakdown and its effects on his family. It’s shimmering and sorrowful, and the writing is extraordinary. Too Much Lip (UQP, 10/18) by Melissa Lucashenko is a strong, unflinching novel about homecoming and history. With trademark wit and lucidity, Lucashenko connects the lives of her sharply drawn characters to a dysfunctional national story. Enza Gandolfo’s The Bridge (Scribe, 5/18), set among working-class lives, considers the collapse of the Westgate Bridge alongside a contemporary tragedy. It’s a moving, unsentimental novel about ethical complexities. Ghachar Ghochar (Faber, 2015) is a disturbing novella by Vivek Shanbhag (translated by Srinath Perur) about an Indian family that becomes wealthy – a gem. Axiomatic by Maria TumarkinI was most excited by two ambitious and wild books of non-fiction, Maria Tumarkin’s Axiomatic (Brow Books, 9/18) and Leslie Jamison’s The Recovering: Intoxication and its aftermath (Granta, 8/18). Tumarkin’s book is breathtaking in its audacity, its deep empathy, and its intellectual rigour. It’s unlike anything I have ever read. The Recovering is a deeply affecting and complex blend of biography and autobiography, drawing intimate and affirming portraits of what it might mean to come back from addiction and illness. My favourite work of fiction was Ceridwen Dovey’s taut and thrilling In the Garden of the Fugitives (Hamish Hamilton, 3/18), which is about trauma and legacy and how we understand the past. It is full of images of tragic beauty.

Axiomatic by Maria TumarkinI was most excited by two ambitious and wild books of non-fiction, Maria Tumarkin’s Axiomatic (Brow Books, 9/18) and Leslie Jamison’s The Recovering: Intoxication and its aftermath (Granta, 8/18). Tumarkin’s book is breathtaking in its audacity, its deep empathy, and its intellectual rigour. It’s unlike anything I have ever read. The Recovering is a deeply affecting and complex blend of biography and autobiography, drawing intimate and affirming portraits of what it might mean to come back from addiction and illness. My favourite work of fiction was Ceridwen Dovey’s taut and thrilling In the Garden of the Fugitives (Hamish Hamilton, 3/18), which is about trauma and legacy and how we understand the past. It is full of images of tragic beauty.

There is nothing good to be said about the news that eleven humanities grants, recommended via rigorous peer review, were vetoed in secret by former Education Minister Simon Birmingham. What makes it worse is that all eleven were humanities projects. Let us remember that humanities only gets around ten per cent of Australian Research Council grants anyway. Quite apart from the good work that won’t get done and the talent that will leave our shores (at least one scholar whose early career grant was vetoed has gone overseas), the damage is twofold: the knock to public faith in expert review caused when it is politicised; and real career damage for those targeted (at least one scholar’s promotion was slowed as a direct consequence).

There is nothing good to be said about the news that eleven humanities grants, recommended via rigorous peer review, were vetoed in secret by former Education Minister Simon Birmingham. What makes it worse is that all eleven were humanities projects. Let us remember that humanities only gets around ten per cent of Australian Research Council grants anyway. Quite apart from the good work that won’t get done and the talent that will leave our shores (at least one scholar whose early career grant was vetoed has gone overseas), the damage is twofold: the knock to public faith in expert review caused when it is politicised; and real career damage for those targeted (at least one scholar’s promotion was slowed as a direct consequence).