- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: Tom Griffiths reviews 'Hugh Stretton: Selected writings' edited by Graeme Davison

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a deeply rewarding and timely book. Hugh Stretton (1924–2015) was one of Australia’s finest public intellectuals, a historian, ABC Boyer Lecturer, and social democrat with a steely mind and a calm, clear voice of wisdom. Stretton spent thirty years arguing thoughtfully against neoliberalism, a critique he developed ...

- Book 1 Title: Hugh Stretton: Selected writings

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $32.99 pb, 336 pp, 9781760640743

This selection of Stretton’s writings, skilfully edited by Graeme Davison, ranges from the late 1960s to the early 2000s and includes a glimpse or two of Stretton’s earlier self (such as his 1945 successful application for a Rhodes Scholarship). Stretton was a prodigy and a genius who lived modestly and remained humble. He was honoured and admired in his lifetime, indeed recognised very early as an extraordinary intellect with moral authority. He was appointed a professor at the University of Adelaide before the age of thirty, and resigned both title and salary for a readership at the age of forty-four to enable more intensive writing. He wrote about cities, housing, economics, the social sciences, and the practice and uses of history. My favourite quote from Stretton is about historians, and I’m delighted it’s in the book: ‘Who study societies of every kind, study them whole, know most about how they conserve or change their ideas and institutions, write in plain language, and generally know how uncertain and selective their knowledge is at best? Historians do.’ Stretton was an ardent champion of historical thinking and believed that history, at its best, possessed three qualities that have been scarce in modern social science: it is holist, uncertain, and eclectic.

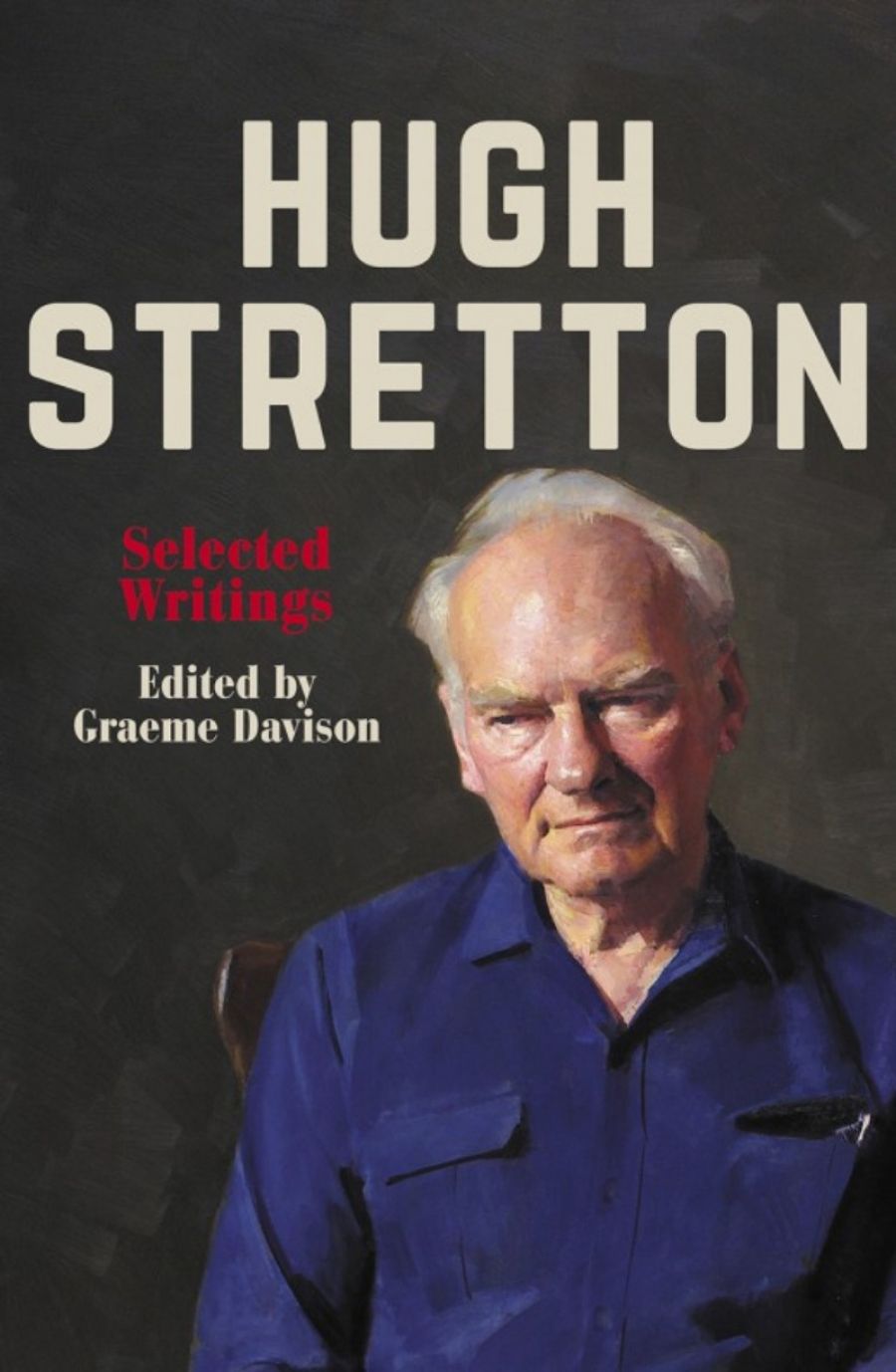

Portrait of Hugh Stretton, 1992 by Robert Hannaford

Portrait of Hugh Stretton, 1992 by Robert Hannaford

Perhaps the most powerful essay in the book, and one Davison calls ‘the angriest and most revealing’, is ‘The Cult of Selfishness’, written in 1987 as a new and virulent strain of liberalism took hold of both sides of Australian politics. In his typically balanced and fair-minded way, Stretton analysed the possible causes of this diffuse ‘political and cultural sea change’, the cult of self or selfishness with its growing condemnation of altruism and encouragement of greed. He was, of course, discerning the dominant political dogma of the next thirty years, a creed now discredited, its vulgarities exposed. Stretton foresaw it all and tried to warn us. It is worth reading this book just to be reminded that a calm, devastating analysis of neoliberalism was available from its beginnings.

Stretton had long been a critic of supposedly objective, value-free social science – his first book, The Political Sciences (1969), was on that subject – and in his 1987 essay on selfishness he savagely critiqued the discipline of economics for its complicity in fostering greed, its delusion that it can be a precise deductive science, and its ‘degrading ideology’ that selfishness is right and sensible. He especially lamented the reconstruction of the curriculum of higher education, a corporatisation of universities that has only escalated since he wrote. It resulted, he argued, in graduates whose heads were empty of deep moral and social reflection and whose ‘inner life of memory and imagination’ had been impoverished.

But Stretton was an optimist and a practical reformer, and so he turned, as ever, to solutions, holding onto his faith that one should treat intellectual adversaries with respect and that good argument can change minds. ‘We the intellectuals should work at it,’ he urged: the novelist and poets, the journalists and academics ‘can apply the acid to the cult of selfishness’. Stretton himself wrote a huge revised textbook of economics (Economics: A new introduction, 1999) and a manifesto on how to make Australia a fairer society (Australia Fair, 2005).

Gaeme Davison (photograph via Black Inc.)Davison’s introduction is itself a significant essay. A pioneer of urban history and an active contributor to planning and conservation debates, Davison is able to place Stretton’s oeuvre in the context of twentieth-century Australian intellectual history, policy, and practice. The city – and the distinctive Australian suburb – were at the centre of Stretton’s work and thought as they are for Davison. Stretton’s Ideas for Australian Cities (1970) was his most popular and influential book: it challenged the condescension of intellectuals for their own urban neighbourhoods. He was a champion of the smaller, planned cities of Adelaide and Canberra and was one of the first Australian writers to sympathetically analyse the suburb, taking a keen interest in the domestic lives of its inhabitants. His 1970 essay ‘Australia as a Suburb’ asks: ‘Why do so many Australians choose to live in a way so unfashionable with intellectual urbanists – twelve or twenty to the acre, halfway between real bush and real city?’ And in his essay on ‘A Good Australian City’, Stretton confesses: ‘I know what I want. I want what I’ve got. A house of my own, where I can sit under a vine in my own backyard; a park somewhere near, where kids can kick a football; a short walk to Tom the Cheap and a local pub; an easy trip to work in the city; half an hour’s drive maybe to a beach or some open country.’

Gaeme Davison (photograph via Black Inc.)Davison’s introduction is itself a significant essay. A pioneer of urban history and an active contributor to planning and conservation debates, Davison is able to place Stretton’s oeuvre in the context of twentieth-century Australian intellectual history, policy, and practice. The city – and the distinctive Australian suburb – were at the centre of Stretton’s work and thought as they are for Davison. Stretton’s Ideas for Australian Cities (1970) was his most popular and influential book: it challenged the condescension of intellectuals for their own urban neighbourhoods. He was a champion of the smaller, planned cities of Adelaide and Canberra and was one of the first Australian writers to sympathetically analyse the suburb, taking a keen interest in the domestic lives of its inhabitants. His 1970 essay ‘Australia as a Suburb’ asks: ‘Why do so many Australians choose to live in a way so unfashionable with intellectual urbanists – twelve or twenty to the acre, halfway between real bush and real city?’ And in his essay on ‘A Good Australian City’, Stretton confesses: ‘I know what I want. I want what I’ve got. A house of my own, where I can sit under a vine in my own backyard; a park somewhere near, where kids can kick a football; a short walk to Tom the Cheap and a local pub; an easy trip to work in the city; half an hour’s drive maybe to a beach or some open country.’

My only meeting with Hugh Stretton was about his father, Leonard, whose Australian Dictionary of Biography entry I was writing. I met Hugh at his beloved North Adelaide home in 2000 and we went for a walk to a Tom the Cheap supermarket. He waxed lyrical about his inner-city suburban life, sang the virtues of Canberra (rare praise of the city to which I’d recently moved), and welcomed the chance to talk about his impressive father. Leonard Stretton was a Victorian County Court judge who conducted five Royal Commissions, including one into the causes of the Black Friday 1939 fires. Stretton’s powerfully written report was acknowledged as a literary masterpiece and became a prescribed text in Victorian Matriculation English.

Stretton senior, like his son Hugh, had strong principles, moral vision, and political audacity. Both were humanists committed to the complexity of life and to understanding and improving it through open-minded empirical inquiry into lived experience. It is instructive to read Hugh Stretton’s advice on ‘How Not to Argue’, his injunction to ‘credit opponents with as much good intent as we believe we have ourselves’, and his reminder that, ‘Facts are facts, but theories order them and explanations select them.’ Values, therefore, are central to any debate and cannot be expunged by pseudo objectivity. In the age of fake news, social media shouting, and the failure of neoliberalism, it’s time to read Stretton again and to attend carefully to this Australian philosopher of fairness.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment