- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: Francesca Sasnaitis reviews 'The Man on the Mantelpiece: A memoir' by Marion May Campbell

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1952, Marion May Campbell’s father was killed in an apocalyptic accident when his World War II RAAF Dakota was knocked out of control by contact with a waterspout and was ‘unable to effect recovery’. There were no survivors and little wreckage. The outmoded Dakota was on loan to the CSIRO to ...

- Book 1 Title: The Man on the Mantelpiece

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $24.99 pb, 232 pp, 9781760800031

Readers will not find the cosy chronology of a life in The Man on the Mantelpiece. In her fiction, poetry, and academic writing, Campbell continues to interrogate the self in relation to contemporary literary practice. The few known facts of her father’s life provide the barest scaffolding for unravelling her ideas. In a theoretical incarnation of a chapter from the memoir, published in Offshoot: Contemporary life writing methodologies and practice (UWAP, 2018), Campbell clarifies: ‘You don’t write out of plenitude. You write to summon the lightning through which the missing might crackle’, thus serendipitously providing The Man on the Mantelpiece with a fitting epigraph.

For readers unfamiliar with the term, life writing refers to a hybrid genre that blurs the conventions of literature and memoir, fiction and non-fiction. It is a form replete with contradictions and connections. Composed of disparate fragments, repetitions, coincidences, and failures in memory and communication, it embraces invention, speculation, embellishment, and emotional truth in favour of empirical proof. It encourages ‘marginal’ writing that demands concentration and commitment of the reader. If it is like Campbell’s experiment in excavation, it rewards with ravishing, extravagant prose.

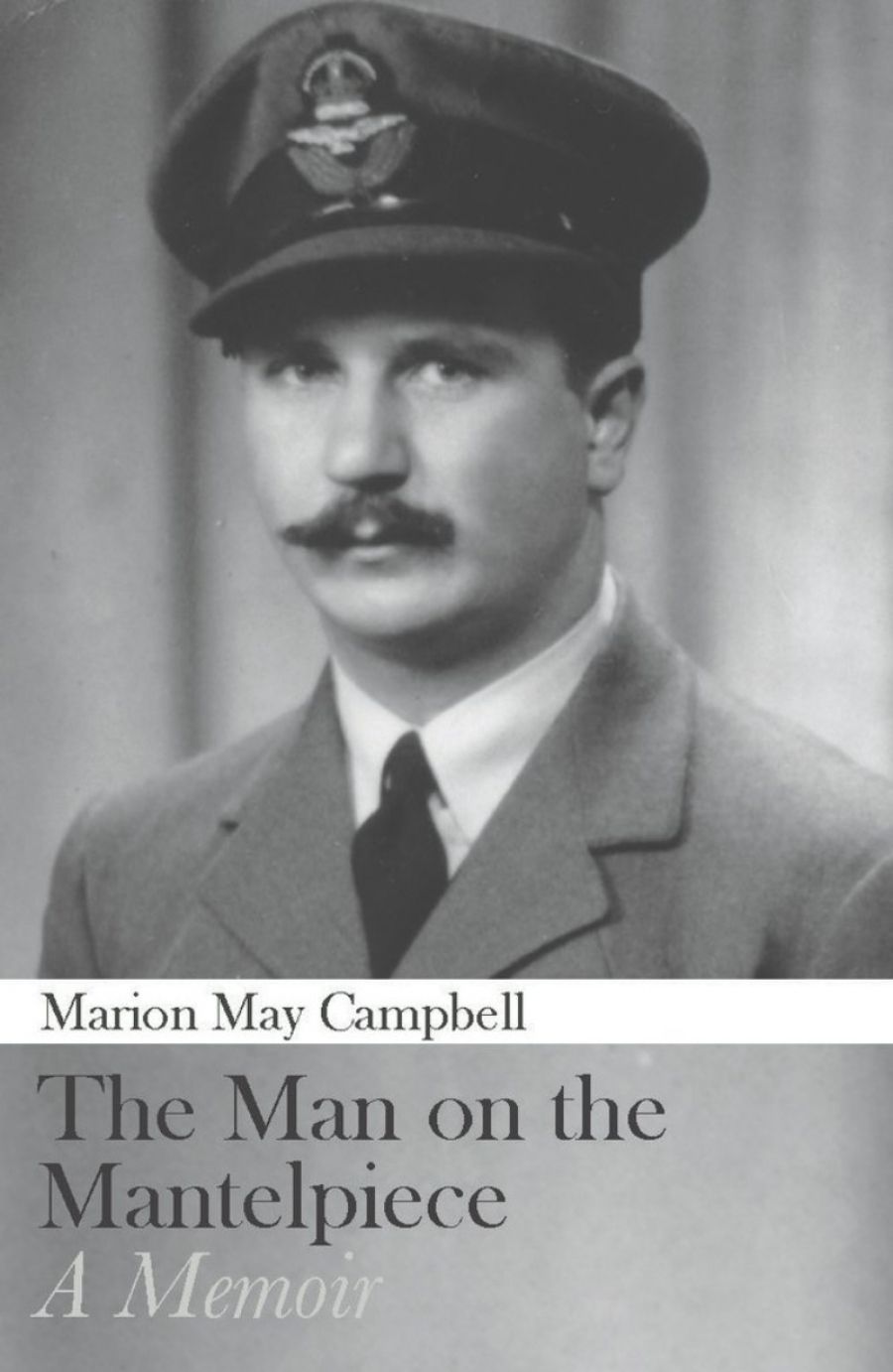

For Campbell, the ‘inaugural scene, from which writing sprout[s]’ (Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, 1993) is the death of her father Frederick ‘Fred’ William Campbell. He is the handsome, uniformed fellow sporting a handlebar moustache, transposed from the mantelpiece to the book cover. The author does not provide an easily devoured narrative of her search for the ‘truth’ behind his disappearance, but delivers information as it might occur to a child, the daughter of a vanished father. Minus the moustache, the cover photograph could be mistaken for a portrait of the author in drag.

Marion May Campbell (photograph via YouTube)

Marion May Campbell (photograph via YouTube)

Campbell was four when her father died; scarcely a memory remains to her. She is reliant on the keeper of the archive, her elder sister, and on the facts ‘little sister’ gleans from official records. She compensates for unreliable memories and a paucity of documentary evidence with ‘rumours, supposition, the strange comfort of conspiracy theories’, and her gift for pouring herself into scene and character. She has had practice. As the ‘orphaned’ daughter, she tries to transform herself into the dead father, partly to console her bereft mother, Roma, but also as a way of knowing him. ‘I dress myself in myth,’ she says, and clothes herself in her parents’ personalities, trying on their early lives and intimacies. Campbell finds signs of love, longing, and relationship in their few remaining photographs. Her ‘reading’ may be fanciful, but who can say if it’s incorrect?

The photograph on the mantelpiece acts as one springboard. Later, ghosts find their way back into the text through allegory and dream. Are the Enchantress and Ventriloqueen a manifestation of lover, mother, or daughter? One or all? Each holds the author in thrall. Bitter Roma would rather kill herself than acknowledge that her daughter might be gay. Roma would rather see her daughter lonely than happy. The daughter is both Rapunzel and Rumpelstiltskin, Sleeping Beauty and the spindle. She has learned the efficacy of her name – Campbell means ‘crooked mouth’. If throwing the witch from the tower doesn’t effect escape, she can try dismemberment and disappearance – an allusion to anorexia – or the maudlin solace of alcohol, anywhere ‘wounded consciousness can be drowned’. But only momentarily. Finally, it is writing that saves her, that gets it right. The torrent of words sings self into being and grants a belated reconciliation between mother and daughter. Campbell laments the loss of stories she failed to receive while Roma was still alive.

The bare facts are extraordinary but give no sense of the unfolding of Campbell’s borrowed memories, meted out in poetic convolutions and dreamlike conjunctions. She is the ‘sunstruck daughter of a man who would have made it rain’. He is the body that was never found, who dies a second time when the family’s belongings are incinerated in a warehouse fire. Fred the rainmaker is a character stepped from fairy tale. Like Randolph Stow’s Michael Random (Tourmaline, 1963) or Bill Starbuck, the character Burt Lancaster plays in the film The Rainmaker (directed by Joseph Anthony, 1956), Fred comes to the story as charlatan and saviour. It does not really matter which he was: he is ultimately unknowable. What counts is what happens in his absence; what those remaining suffer; how lives evolve.

The daughter grows up with a deified father and her mother’s rejection of any new liaison, none of whom lives up to Fred’s exalted standard. ‘You will never be as good as Him, you will never be as good as the Unfallen Dead’ is what the daughter learns about the missing. You can’t compete with memory.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment