- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

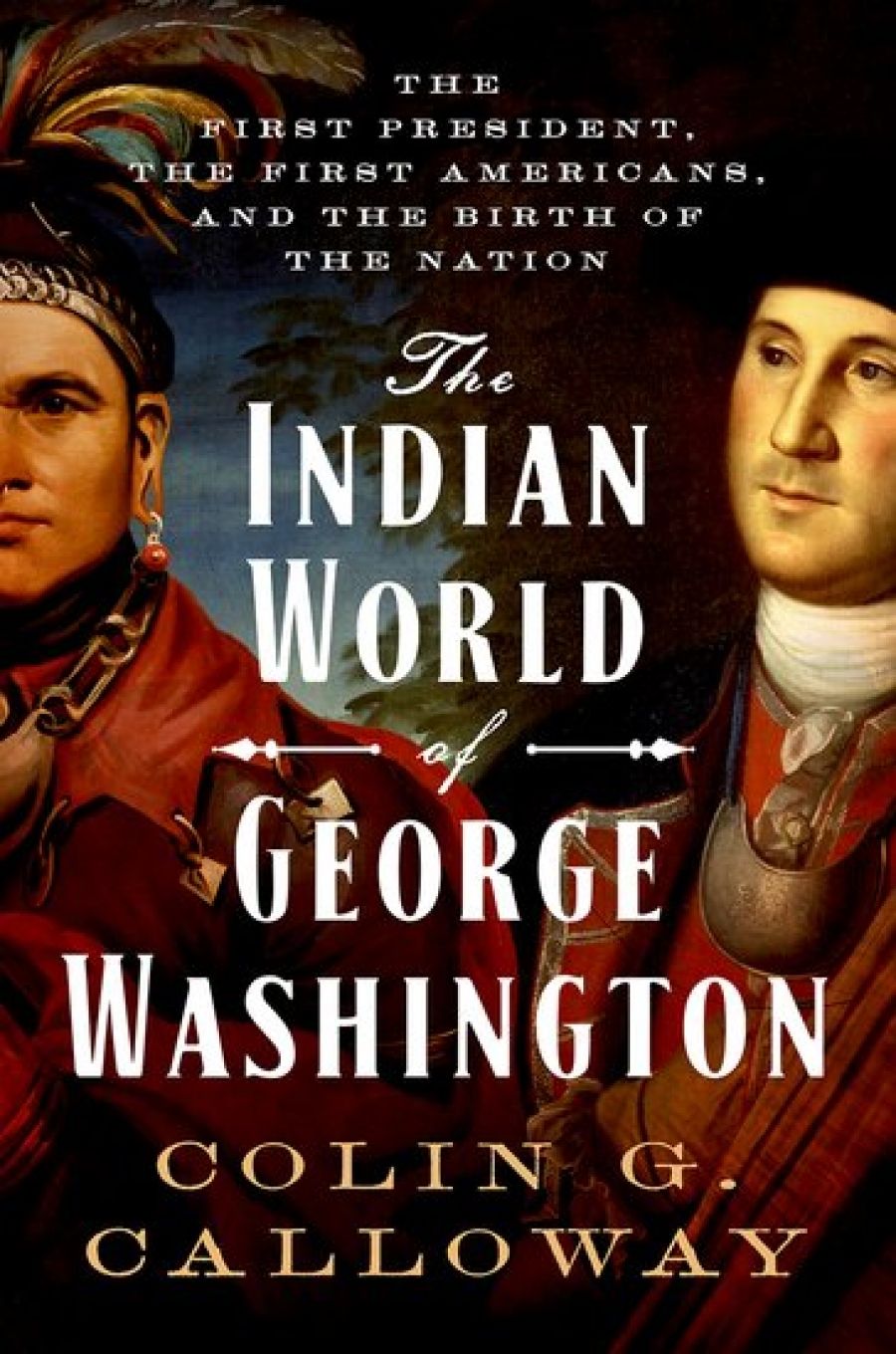

- Custom Article Title: Josh Specht reviews 'The Indian World of George Washington' by Colin G. Calloway

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a young man, George Washington (1732–99) worked as a surveyor. Looking at a landscape, he could plan its division into orderly tracts. These skills would prove useful when he became the first president of the United States in April 1789. At the time ...

- Book 1 Title: The Indian World of George Washington

- Book 1 Subtitle: The first president, the first Americans, and the birth of the nation

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $53.95 hb, 640 pp, 9780190652166

Colin G. Calloway’s The Indian World of George Washington is a narrative of early America told through the biography of its most influential person. Interaction with American Indians, as allies and enemies, in diplomatic negotiations and on the battlefield, was at the centre of Washington’s life. So, too, was this interaction at the heart of the story of early America. Early in Calloway’s book, Washington, as well as the American colonies more broadly, are in over their heads when it comes to American Indian geopolitics. A young George Washington, tasked with his first real military responsibility, is manipulated by an Iroquois leader named Tanaghrisson into a conflict with French forces that would help spark the globe-spanning Seven Years’ War (the North American theatre of the conflict was known as the French and Indian War). Rival American Indian factions, seeking their own security by pitting land-hungry European powers against one another, sided with either the British or French. Ensuing Indian raids would reveal colonists’ vulnerability, but also unite them in a shared fear of Indian might as well as a collective desire for reprisal. By the time of the American Revolution, we find Washington and much of the colonial élite angry about crown policies limiting settlement of lands in which this élite was heavily invested. In the Revolution’s aftermath, the United States was free to expand without European influence. Washington hoped that American Indians would freely sell their land and cheerily adopt ‘civilised’ ways of life, but there was no doubt that the United States would get the land, either by sale or by force.

The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West. It depicts the death of British General James Wolfe during the French and Indian War (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West. It depicts the death of British General James Wolfe during the French and Indian War (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Over the course of his life, Washington’s views about American Indians changed little. As a young soldier, he was unimpressed by seemingly capricious Indian allies but excited about the possibilities of Indian land. Early failures, including his disastrous relationship with Tanaghrisson, gave Washington a bit more experience dealing with American Indians, but his overall views changed little. What did change for both Washington and the United States, though, was the ability to act on these views. As Calloway explains, in his early life Washington ‘addressed Indians as brothers and negotiated the terms of his relationship with them; as President, he addressed them as children and mandated policies for them’. Meanwhile, the United States evolved from a settler-colonial society ‘held back by Indian power and anxious for Indian allies to an imperial republic that was on the move, dismantling Indian country to create American property, and dismantling Indian ways of life to make way for American civilization’.

There are many fascinating stories and details in Calloway’s book. For instance, in the 1790s the streets of then-capital Philadelphia were filled with rival American Indian delegations. At times, however, these details obscure Calloway’s larger point. Tales of state dinners with Cherokee diplomats certainly challenge our view of early American politics, but by the end of the book I was unsure how diplomacy related to the inexorable loss of Indian land. Similarly, Washington’s relationship with squatters – as a land speculator and as a president – looms large in the story. Both parties needed each other: squatters to do the day-to-day dirty work of dispossession and settlement, and élites to occasionally bring the full might of the American state onto intractable Indians. Calloway observes that, once in power, Washington ended up dealing with frontier areas in much the same way as the British crown (managing pioneers and squatters with temporary settlement boundaries), but the connection of this observation to the broader process of settler-colonialism is unclear.

George Washington by Charles Willson Peale, 1776 (photo via WIkimedia Commons)Calloway’s book persuasively shows that American Indians were at the centre of Washington’s life and the early American world. It is an account that tells us a lot about territorial expansion and settler-colonial violence in early American history. Yet at times, maintaining a simultaneous story of Washington as person and Washington as symbol of broader American development becomes too much to manage. The closing chapters of the book provide a twist to the story of George Washington, land speculator. As it turns out, Washington never really profited from his schemes. Failed or inconclusive lawsuits against squatters and letters to cash-strapped relatives about his own financial woes highlight that there was more to land than deeds or maps.

George Washington by Charles Willson Peale, 1776 (photo via WIkimedia Commons)Calloway’s book persuasively shows that American Indians were at the centre of Washington’s life and the early American world. It is an account that tells us a lot about territorial expansion and settler-colonial violence in early American history. Yet at times, maintaining a simultaneous story of Washington as person and Washington as symbol of broader American development becomes too much to manage. The closing chapters of the book provide a twist to the story of George Washington, land speculator. As it turns out, Washington never really profited from his schemes. Failed or inconclusive lawsuits against squatters and letters to cash-strapped relatives about his own financial woes highlight that there was more to land than deeds or maps.

The financial struggles of Washington the man reveal the limits of Washington the symbol. Now that Calloway has shown us that American Indians and their land were central to the story of early America, perhaps we need to look to the squatters, and their relationship with both American Indians and political élites, to fully understand the violent process by which the United States went from land ownership on paper to land ownership on the ground.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment