- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: Felicity Plunkett reviews 'Dangerous Ideas about Mothers' edited by Camilla Nelson and Rachel Robertson

- Custom Highlight Text:

An essay at the heart of this collection, ‘Against Motherhood Memoirs’ by Maria Tumarkin, is not as insistent as its title suggests. Tumarkin, interested in ‘fissures and de-fusion’, troubles the awkward spots in her analysis. While reading Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) – which places ‘motherhood and queerness side by side’ with ...

- Book 1 Title: Dangerous Ideas about Mothers

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.99 pb, 246 pp, 9781742589909

Nelson’s work about love, connection, and the forms they take – and might be expressed through – probes ideas of articulation, doubt, and silence, variously fructive, disguising, or censorious. She writes about how, ‘feral with vulnerability’, any of us may try to stay present with ‘unnameable things, or at least things whose essence is flicker, flow’. Nelson’s work undoes seams where the sayable and unsayable meet, wanting neither easy ways of thinking that ‘ride roughshod over specificity’ nor ‘to make a fetish of the unsaid’.

This commitment to uncomfortable complication underpins both Tumarkin’s work and this collection’s exploration of thinking about motherhood and the ‘dangerous ideas’ that may disturb it. Tumarkin, interrogating the ‘over-memoirisation of motherhood’, despises hackneyed criticism of the form, recognising its origins in habitual imagining of a ‘wobbly, hormone-affected’ mother as ‘the least interesting [thinker] of our culture’.

Maria Tumarkin (photo via The Wheeler Centre)

Maria Tumarkin (photo via The Wheeler Centre)

The restive energy of Tumarkin’s work exemplifies an adventurous spirit running the collection. The first sentence of editors Camilla Nelson and Rachel Robertson’s introduction – ‘Mothers are a topic on which almost everybody has an opinion’ – begins an exploration of the contested nature of motherhood as symptomatic of a moralising culture that pits women against each other. Nelson and Robertson contextualise this within a rise in social media phenomena such as Instagram ‘brelfies’, celebrated for both championing breastfeeding and criticised for marginalising non-breastfeeding mothers. Yet many of these debates are long-standing. When Virginia Woolf wrote in Three Guineas (1938) that women have thought ‘while they stirred the pot, while they rocked the cradle’, critic Q.D. Leavis was quick to quip that the (childless) ‘Mrs. Woolf wouldn’t know which end of the cradle to stir.’

There is a flood of bilious commentary about mothers that wears the mask of Schadenfreude. Anne Manne quotes historian John Hirst in The Age, who described single mothers as ‘given to junk food, daytime TV and no-good boyfriends’, and Joe Hockey’s distinction between ‘leaners’ and ‘lifters’, the former being those outside paid employment. Emma A. Jane’s ‘bolshie corrective’ to Hirst-style stereotypes of single mothers is disrupted by the experience of choking on a prawn, and a moment of feeling ‘conspicuously and … wrist-slittingly alone’. While Jane’s witty and steely riposte to One Nation candidate David Archibald’s equation of solo mothering with a rise in ‘the portion of the population that is lazy and ugly’ offers a portrait of a loved child held within communities of affinity and care, that image of aloneness thrums beneath it. The profound vulnerability suggested by slit wrists is more than a jaunty aside.

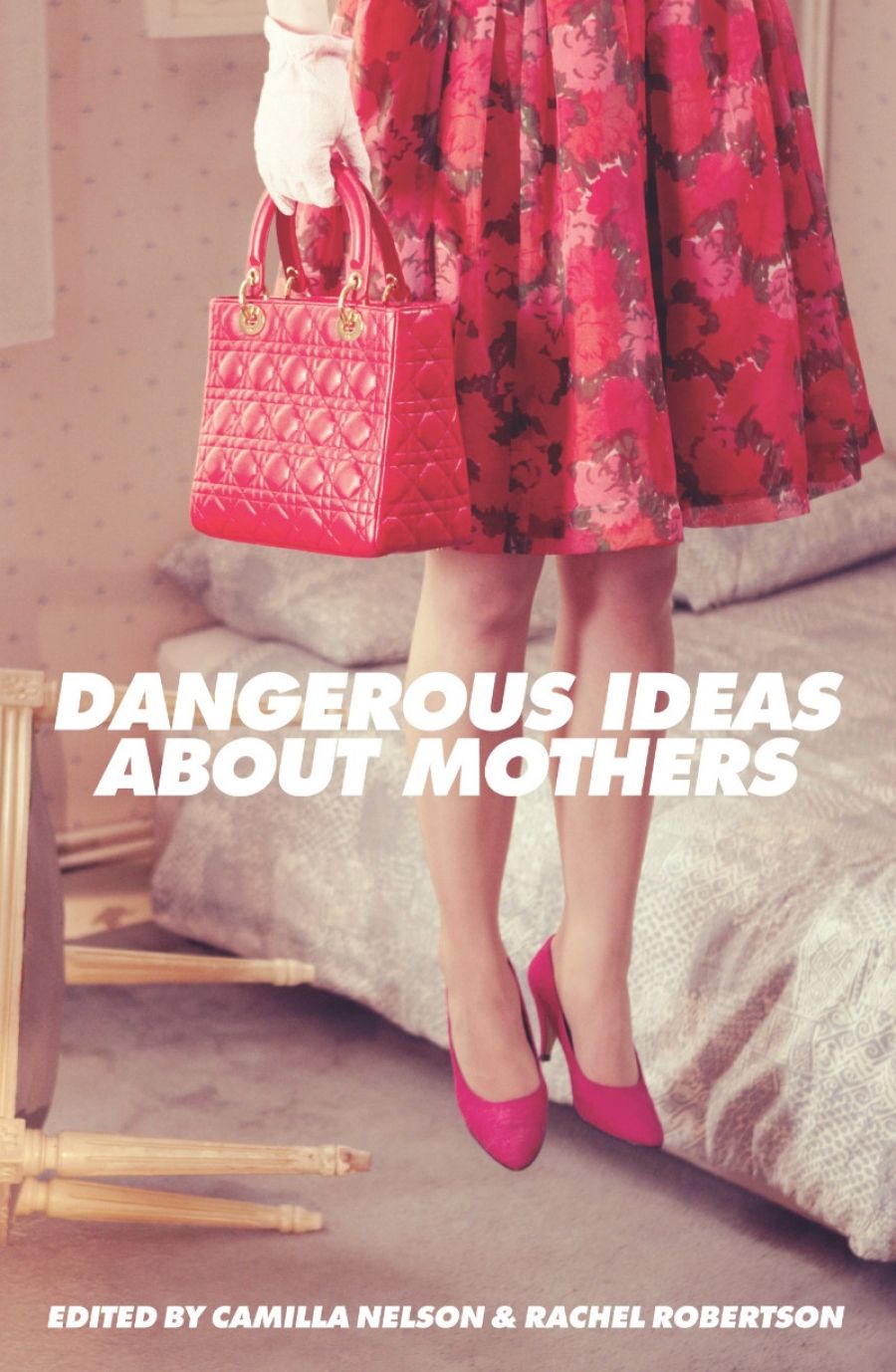

The cover’s detail from Kourtney Roy’s photo Rope – a balletic feminine figure, on closer inspection, the body of a woman who has hanged herself – warrants discussion. While it may suggest a disjunction between what we see at a glance (elegance, glamour, poise) and what is really going on (life-threatening despair), it seems a glib choice.

Post-partum psychosis affects one or two in every thousand mothers; post-partum depression affects one in seven. Post-partum suicide is one of the leading causes of death in new mothers. While much of the writers’ work here is to draw attention to mothers, this cover seems far less attuned – and even naïve about or trivialising of – maternal mental health. Some readers most likely to benefit from this empathetic work may find this image repellent or even dangerous.

The collection tirelessly questions stereotypes of mothering. Some are risible, some fan panic. Catharine Lumby examines anxiety about screen time, asking whether ‘reading a book is automatically more intellectually stimulating or productive than reading or watching something on a screen’. She brings children’s voices to the discussion, expressing their joy ‘in entering an imaginary world’ and advocating the tenacious work of ‘guiding our kids through the shallow and deeper waters of being human’.

Camilla Nelson describes monitoring screen time as a ‘middle-class preoccupation’. Her exploration of ‘Mumpreneurism’ catalogues the hashtags, emojis, and purchasing links associated with the ‘branding’ of photogenic children, and the genteel scorn of, for instance, images of a (confected) child, Quinoa. Is this scorn the same as Waleed Aly’s criticism of celebrity Roxy Jacenko, whose images of her four-year-old daughter were investigated as part of an obscenity case? Aly’s critique might be seen as expressing the rights of a child who cannot have agency when it comes to subtle questions of voyeurism, money, and consent.

Anne Manne argues for an ethics of care. In an exhilarating moment, she imagines an otherwise well-qualified job applicant dismissed on the basis of showing no evidence of time spent on the care of others. Alecia Simmonds’s ‘Domesticating Violence’ is a similarly clear-eyed analysis of domestic violence.

Hazel Smith prefaces her sensitive discussion of voluntary childlessness with an experimental prose poem, while Quinn Eades writes in lyrical slivers about ‘Being a Boy Mama’. The exhilarating diversity of forms here – among them lyrical, poetic, and autotheoretical – expresses the range of angles on mothering, as well as the shifting, mobile terrain of non-fictional prose itself.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment