- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Zora Simic reviews 'Unfettered and Alive' by Anne Summers and 'Germaine: The life of Germaine Greer' by Elizabeth Kleinhenz

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Anne Summers first met Germaine Greer at a raucous house party in Balmain in the early 1970s, she threw up in front of her after too many glasses of Jim Beam. Almost fifty years later, she muses that perhaps that early encounter was one of the reasons why they ‘never really connected’ ...

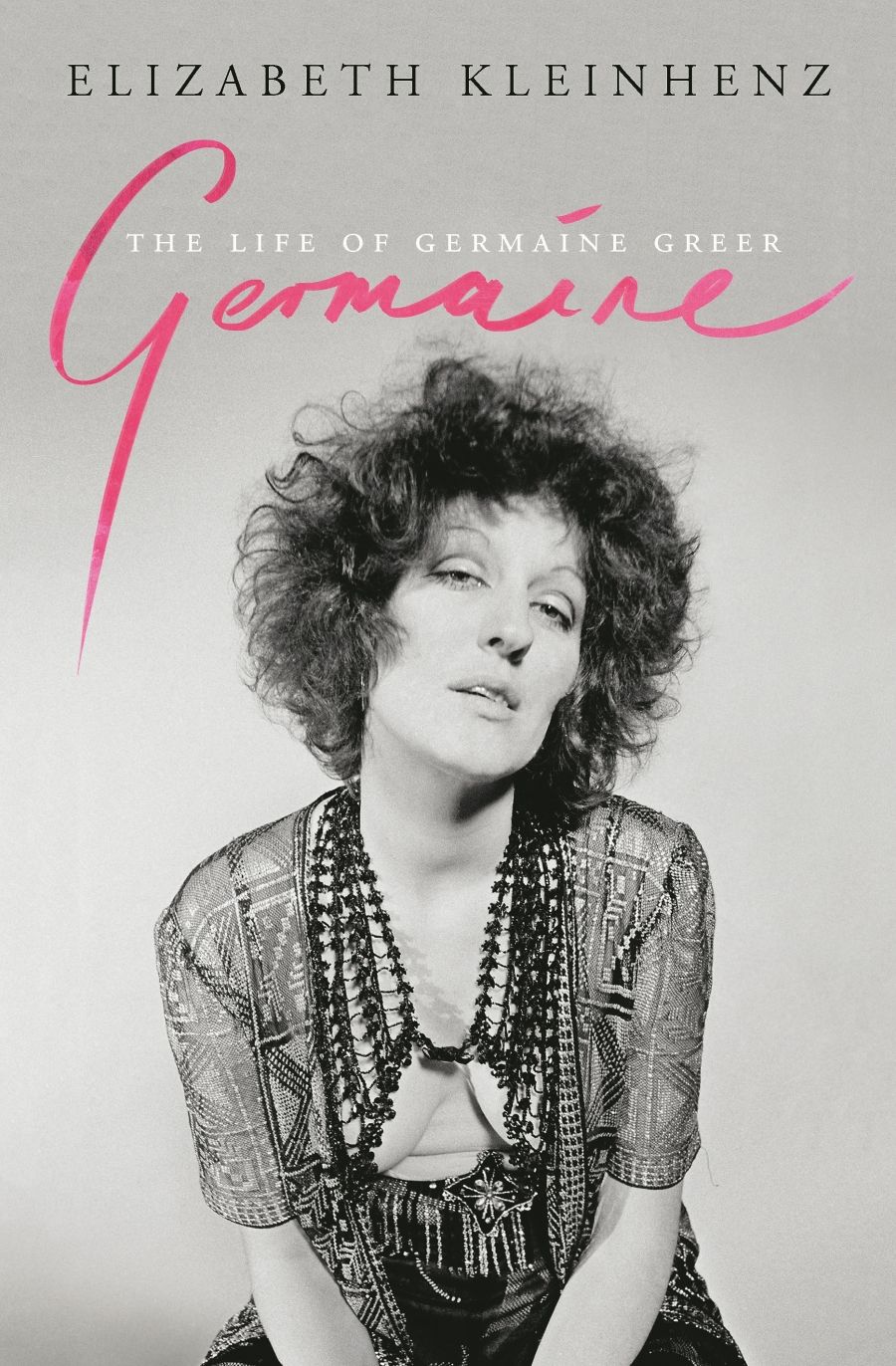

- Book 1 Title: Germaine

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Germaine Greer

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $39.99 hb, 432 pp, 9780143782841

- Book 2 Title: Unfettered and Alive

- Book 2 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $39.95 hb, 512 pp, 9781743318416

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Online_2018/December/Unfettered.jpg

On many counts, Summers and Greer appear to have much in common, including fairly equal claims to being two of the most influential feminists in Australian history. More or less contemporaries – Greer was born in 1939, at the onset of World War II, Summers at its end, in 1945 – they were educated by nuns before escaping their stifling suburban upbringings for higher education and 1960s bohemia. Each of them made her mark early with ground-breaking books, Greer with The Female Eunuch (1970), Summers with Damned Whores and God’s Police (1975), one of the first major histories of Australian women. Both women were briefly married – Greer for a month – and didn’t have children. They enjoyed international success and wrote best-selling books about a parent, with mysteries at their core: Greer’s Daddy, We Hardly Knew You (1989) and Summers’ The Lost Mother (2009). Neither woman has shied away from criticising younger feminists for perceived failings. They remain high-profile public figures. In 2011, Greer and Summers were honoured as Australian Legends by Australia Post in a series of commemorative stamps.

Beyond public accolades, there are other similarities. Both women have been candid about their reproductive histories Greer, who tried to have a child, has expressed regret and some anger about hers; Summers, in her memoir, is matter-of-fact about her abortions. They share a strong commitment to living a free life, defined in their own terms. They made money and bought their own homes at a time – not very long ago – when it was still unusual for women to do so. Summers recounts her bank initially refusing to finance her mortgage back in the late 1970s, though she was making more than enough money as a member of the Canberra press gallery. Greer, meanwhile, as Kleinhenz traces, has bought, renovated, gardened, populated, and sold a series of memorable properties. These include her beloved cottage ‘Pianelli’ in Tuscany, where Greer once had a tryst with Federico Fellini.

Germaine Greer in 1972 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)Summers takes the title of her memoir from a Joni Mitchell song, but it’s another freedom seeker, French feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, who acts as lodestar. This is immediately apparent in her choice of epigraph, drawn from The Second Sex (1949), correctly translated to begin, ‘One is not born, but rather becomes woman’, rather than ‘becomes a woman’, as Summers first read it in her youth. This seemingly minor difference ‘might seem innocuous’, writes Summers, but ‘the intended formulation was much stronger than the one served up to us’. In her closing tribute, Summers also reflects that the life of ‘this strange French woman’ – the one she most aspired to emulate as a young Australian woman – was not as free as she had once thought, because ‘Beauvoir was a doormat when it came to men’. Still, if her younger self might have been harsher in her judgement, Summers is now more inclined to situate her hero in historical context. This generous yet clear-eyed sensibility animates the entire book, even when she is settling old scores.

Germaine Greer in 1972 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)Summers takes the title of her memoir from a Joni Mitchell song, but it’s another freedom seeker, French feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, who acts as lodestar. This is immediately apparent in her choice of epigraph, drawn from The Second Sex (1949), correctly translated to begin, ‘One is not born, but rather becomes woman’, rather than ‘becomes a woman’, as Summers first read it in her youth. This seemingly minor difference ‘might seem innocuous’, writes Summers, but ‘the intended formulation was much stronger than the one served up to us’. In her closing tribute, Summers also reflects that the life of ‘this strange French woman’ – the one she most aspired to emulate as a young Australian woman – was not as free as she had once thought, because ‘Beauvoir was a doormat when it came to men’. Still, if her younger self might have been harsher in her judgement, Summers is now more inclined to situate her hero in historical context. This generous yet clear-eyed sensibility animates the entire book, even when she is settling old scores.

Greer was much less forgiving in her book The Change (1991), in which she blasted Beauvoir for her dependence on Jean-Paul Sartre and for her fear of ageing. In one of the more perceptive passages in her genial but largely descriptive biography, Kleinhenz notes that there was a larger purpose to this scathing critique: in addressing menopause, Greer was once again ‘in the vanguard of new thinking about an important issue for women’. Indeed, her feminist critique of ageing has been one of Greer’s more refreshing and sustained interventions in recent decades, especially compared to her reactionary position on transgender issues or her well-intentioned but naïve expressions of solidarity with Aboriginal people.

Kleinhenz’s biography is necessarily concerned with her subject’s entire life, while Summers’ memoir picks up where her previous memoir, Ducks on the Pond (1999), left off, in 1976, when the author remains a feminist but no longer a Women’s Liberationist as she moves away from the grassroots movement to new challenges, chiefly newspaper journalism. Yet both books are ultimately about what happens in the aftermath of early success and the first phase of second-wave feminism. Greer and Summers had unusual opportunities to work, travel, and play; their life histories overflow with relocations, encounters with (in Greer’s case especially) famous and influential people, and new audiences or constituencies for their work. Greer became a television personality and newspaper columnist in the United Kingdom, where, among other things, she wrote lovingly about her garden in Essex. In the mid-1980s, when Summers became editor and, soon after, co-owner with Sandra Yates of the trail-blazing but by then rather dour US feminist magazine Ms, among her controversial new features was a regular gardening page.

The infamous cover art for The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer (1970)In their distinctive ways, Greer and Summers championed a style of feminism that resonated with ordinary women, if not always with critics or other feminists. Kleinhenz extracts from the massive Germaine Greer archive – purchased for three million dollars by the University of Melbourne in 2013, and the justification for a new biography – small gems of correspondence from women seeking advice from Greer, who was often firm but kind in response. Summers, meanwhile – first in her capacity as head of the revived Office of the Status of Women under the Hawke government, and later as women’s adviser to Paul Keating – sought to identify what issues mattered most to Australian women by asking them. That some of these issues did not directly affect Summers (childcare) or surprised her for their ongoing significance in women’s lives (such as domestic violence – despite her role in setting up Elsie Women’s Refuge, the first such refuge in Australia) says less about her singularity than it does about her political skills and capacity to listen. Her later affinity with, and admiration for, Julia Gillard, Australia’s first female prime minister, makes even more sense read in the context of Summers’ own history.

The infamous cover art for The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer (1970)In their distinctive ways, Greer and Summers championed a style of feminism that resonated with ordinary women, if not always with critics or other feminists. Kleinhenz extracts from the massive Germaine Greer archive – purchased for three million dollars by the University of Melbourne in 2013, and the justification for a new biography – small gems of correspondence from women seeking advice from Greer, who was often firm but kind in response. Summers, meanwhile – first in her capacity as head of the revived Office of the Status of Women under the Hawke government, and later as women’s adviser to Paul Keating – sought to identify what issues mattered most to Australian women by asking them. That some of these issues did not directly affect Summers (childcare) or surprised her for their ongoing significance in women’s lives (such as domestic violence – despite her role in setting up Elsie Women’s Refuge, the first such refuge in Australia) says less about her singularity than it does about her political skills and capacity to listen. Her later affinity with, and admiration for, Julia Gillard, Australia’s first female prime minister, makes even more sense read in the context of Summers’ own history.

The original cover of Damned Whores and God's Police by Anne Summers (1975)Greer’s feminism – provocative, polemical, and intensely personal – travelled in two main, and sometimes conflicting, directions: scholarship and mainstream celebrity. Kleinhenz dutifully provides summaries of Greer’s canon and sketches a portrait of ‘Germaine [as] a natural scholar who rarely feels more in control of her life than when she is sitting in libraries fossicking through books and papers’, but, as a biographer, Kleinhenz is better suited to the gossipy aspects of Greer’s life than she is to elucidating her feminism. In a spirited but awkward attempt to capture the impact of Greer’s work on women’s lives, Kleinhenz introduces ‘Cheryl Davis’ from East Doncaster, Melbourne, to whom she intermittently returns in order to trace Greer’s enduring and transformative significance. As a literary device, ‘Cheryl’ offers a creative alternative to the more robust and rigorous analysis of Greer’s work and feminism presented by Christine Wallace in the last major Greer biography, Untamed Shrew (1997). Unfortunately, ‘Cheryl’ is also a reminder that Wallace’s book – so vehemently opposed by Greer at the time that it is now a part of the latest version of Greer’s story, as well as a vital resource for Kleinhenz – is the more substantial one. Wallace may not have had the benefit of access to the Greer archive, but her approach was more fearless and forensic, as well as better historicised.

The original cover of Damned Whores and God's Police by Anne Summers (1975)Greer’s feminism – provocative, polemical, and intensely personal – travelled in two main, and sometimes conflicting, directions: scholarship and mainstream celebrity. Kleinhenz dutifully provides summaries of Greer’s canon and sketches a portrait of ‘Germaine [as] a natural scholar who rarely feels more in control of her life than when she is sitting in libraries fossicking through books and papers’, but, as a biographer, Kleinhenz is better suited to the gossipy aspects of Greer’s life than she is to elucidating her feminism. In a spirited but awkward attempt to capture the impact of Greer’s work on women’s lives, Kleinhenz introduces ‘Cheryl Davis’ from East Doncaster, Melbourne, to whom she intermittently returns in order to trace Greer’s enduring and transformative significance. As a literary device, ‘Cheryl’ offers a creative alternative to the more robust and rigorous analysis of Greer’s work and feminism presented by Christine Wallace in the last major Greer biography, Untamed Shrew (1997). Unfortunately, ‘Cheryl’ is also a reminder that Wallace’s book – so vehemently opposed by Greer at the time that it is now a part of the latest version of Greer’s story, as well as a vital resource for Kleinhenz – is the more substantial one. Wallace may not have had the benefit of access to the Greer archive, but her approach was more fearless and forensic, as well as better historicised.

Summers’ feminist politics are rather different from Greer’s. As she tells us, she is ‘practical’, not afraid of ‘stats and facts’, and has consistently aimed to effect or at least influence real change, whether through activism, journalism, or government bureaucracy. Like Greer, she started out as a scholar, but apart from a fleeting moment of nostalgia for not sticking with the comparatively stress-free pursuit of women’s history, Summers does not share Greer’s abiding veneration of the ivory tower. She thrives on the adrenalin of a deadline or a tightly fought election campaign, as her euphoric account of Paul Keating’s unexpected election win in 1993 demonstrates.

Anne Summers (photo via Facebook)

Anne Summers (photo via Facebook)

As a writer, Summers is instinctively a journalist, with a keen sense of history and character. The soft side of Keating emerges, while Bob Hawke’s abiding appeal is only enhanced by the knowledge that he apparently read The Second Sex. But Summers suffers no fools, and some politicians and feminists come out badly. She is adamant, for instance, that Malcolm Fraser, despite his later rehabilitation as an anti-racism champion, was essentially a ‘tough bastard’; and she prefers the no-nonsense Betty Friedan to Gloria Steinem, whom she depicts as flighty and emotionally stunted. This crude psychological profile seems undeserved, but it is clear that writing this memoir has provided Summers with the chance to clear up unfinished business from her time at Ms. Her account of her time there is convincing.

Unfettered and Alive is a hefty tome; some sections tend to drag. But its size is entirely proportionate with the life lived and the histories that Summers was a part of. Even more so than Ducks on the Pond – now a key text of Australian second-wave feminism – her latest memoir is an important work of social and political history. It is told well by someone with insider access who nevertheless, by virtue of her sex, nationality, and sheer trailblazing novelty, was also an outsider. In her preface, a letter to her younger self, Summers recalls that growing up she had only one positive role model of a free woman, her ‘spinster aunt’ Nance. The equation of freedom with not having children may alienate some, but Summers’ truth, and her defence of it, are persuasive and nuanced.

The best parts of Kleinhenz’s biography are similarly attuned to the costs and pleasures of being Germaine Greer. These two towering figures of Australian feminism may not have personally connected at that Balmain party, but their work and lives will continue to resonate and fascinate for however long the question of what freedom means for women remains an open and contested one.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment