- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: ''Tirra Lirra' and Beyond - Jessica Anderson’s truthful fictions' by Susan Sheridan

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: ‘Everyone I talk to remembers Tirra Lirra by the River as a wonderful book, sometimes even as a life-changing one. But why don’t we hear anything about it today?’ This was a young journalist who ...

‘Everyone I talk to remembers Tirra Lirra by the River as a wonderful book, sometimes even as a life-changing one. But why don’t we hear anything about it today?’ This was a young journalist who had been assigned to write Jessica Anderson’s obituary. Anderson, who died in Sydney on 9 July 2010, was the author of seven novels and a volume of stories, but it was her fourth published book, Tirra Lirra by the River (1978), which won the Miles Franklin Award and made her name as an Australian writer.

The novel opens as an ageing woman, Nora Porteus, returns after a long sojourn in London to the Brisbane house in which she grew up. Her parents, brother and sister are all dead, and neighbours care for her when she falls ill. In her feverish state, Nora becomes possessed by her memories, some consciously recalled, others which return suddenly, evoked by a sight or sound. She has been accustomed to resisting these ‘accidental flicks’, which open onto dark patches on the obscure side of her ‘globe of memory’. Now she cannot entirely control the spinning globe, and along with the ‘truthful fictions’ she has told so often to amuse or shock her London friends come unbidden memories of events she has relegated to the dark side. The novel shuttles back and forth between present and past events, and between ‘truthful fictions’ and traces of the repressed, as Nora tries to set the record straight, to recover memory from the distancing imagination.

Within this narrative framework, the events of Nora’s life are presented through her emotions. Her adolescent longing for something more than dull suburban existence with her mother and sister push her into an ill-considered marriage to the genteelly sadistic Colin Porteus. On moving with him to Sydney, she is happy at first in bohemian Kings Cross, and then miserable, trapped in her mother-in-law’s desperately respectable suburban house. His insistence on a divorce shocks her out of depression and frees her. What sustains Nora through these bad years is the imaginative space she creates through her design and dressmaking work. The dressmaking provides her, belatedly, with the means of earning her own living. Her independent life in London from the late 1930s to the 1960s brings more trials, but it leads her even-tually into the magic circle of friends with whom she shares a house. A dramatic reversal of fortunes brings these good times to an end, and brings Nora, now in her seventies, back to Australia.

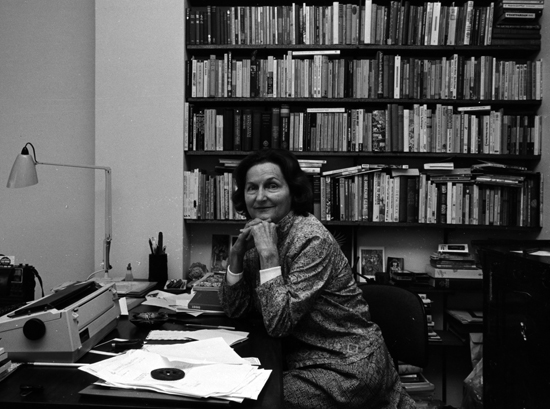

Jessica Anderson, 1986 (photograph by Alec Bolton, National Library of Australia)

Jessica Anderson, 1986 (photograph by Alec Bolton, National Library of Australia)

Nora exhibits a classically feminine combination of compliance and covert rebellion, of social conformity and an outsider’s sensibility. She is aware of performing a range of selves, all of which shape her into the person she is – there is no single self to be discovered below all the layers of social roles. For instance, deriving some pleasure in her ‘surreptitious disobedience’ of the doctor’s orders, she recognises this as a legacy from her marriage, just as she recognises aspects of herself in the ‘gentle’ neighbour who ended her life, and her family’s, in acts of extreme violence.

Like the story of her namesake in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, Tirra Lirra calls out to be read as a woman’s novel in the feminist sense of representing, from the perspective of a particular woman’s subjectivity, female experiences such as sexual initiation, the struggle for economic independence, abortion and ageing. It was certainly read that way during the 1980s, the decade when women writers and feminist questions dominated the literary scene. Yet such is its richness, this short novel has also been read as a quest (as the title suggests, there are Tennysonian echoes of the Arthurian legend), as a novel of city life and as a post-colonial text.

This book was the major success of Anderson’s career, in terms of sales and also critical reception. Translated into Chinese, French, Italian and Danish, and published as a Penguin paperback in the 1980s, it was extensively and enthusiastically reviewed, and has been the subject of many literary critical discussions. It is represented in several recent publications on Australian literature, not only the influential Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature (2009) and Jane Gleeson-White’s Australian Classics: 50 Great Writers and Their Celebrated Works (2007), but also in an anthology aimed at Indian students of Australian literature (Fact & Fiction: Readings in Australian Literature, edited by Amit and Reema Sarwal, 2008) and in several European essay collections on Australian literature. Tirra Lirra clearly has a continuing place in the canon of Australian fiction texts taught internationally, and locally, too: it is currently taught in seven Australian universities and appears on the VCE English syllabus.

It would be unfortunate if Jessica Anderson were to be remembered only for Tirra Lirra by the River, outstanding though it is. The books she published before and after it demonstrate an extraordinary range and depth of talent, within a relatively small compass, as Elaine Barry argues in Fabricating the Self: The Fictions of Jessica Anderson (1996), the only book-length study to date of Anderson’s work. With every novel, she tried her hand at something new. The first two, An Ordinary Lunacy (1963) and Last Man’s Head (1970), employ some of the conventions of crime fiction to explore dramas of sexual obsession acted out in contemporary middle- class Sydney milieux. The Impersonators (1980), which won the Miles Franklin Award for 1980, develops the novel of manners mode that was present in the early novels. In a family rendered complex by divorce and remarriage, the death of the patriarch sets in motion conflict over inheritance, and a love affair between his only daughter and one of his stepsons keeps the two families closely entwined. The shady business dealings that underlay his fortune are paralleled in those of a son-in-law, while a step-son is involved in Sydney’s greedy real estate business.

Anderson’s capacity for grounding her characters in contemporary life provides the setting for Taking Shelter (1989), a novel of manners ‘about love in the early stages of AIDS’, as she described it in an interview. In both this and her last novel, One of the Wattle Birds (1994), the narrative focus is a young woman discovering her capacities for love and deception in her first sexual relationship. In each case, she proceeds without any parental presence but nonetheless surrounded by loving and interfering friends and relations. Cecily, the heroine of One of the Wattle Birds, is, like Nora, the first-person narrator of her story, but the problems that she confronts, following the death of her mother, are a far cry from the ‘waste and waiting’ that marked Nora’s young womanhood in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Commandant (1975), Anderson’s only historical novel was, she said, her favourite because she so much enjoyed doing the research. Its setting is the penal settlement at Moreton Bay in 1830, and its subject is the legend of Patrick Logan. This story was one she heard about as a child growing up in Brisbane in the 1920s, and Logan was the Commandant, immortalised in the ballad called variously ‘Moreton Bay’ or ‘Brisbane Water’, as the ‘tyrant’ whose murder at the hands of ‘the blacks’ is cause for the convicts’ rejoicing. What distinguishes The Commandant from most Australian historical novels – and links it with her contemporary novels – is Anderson’s creation of a nuanced domestic setting in which to dramatise the Commandant’s cruel authority. In this way, the brutality of flogging and putting men in irons is emphasised by contrast with the predominant scenes of the domestic life of the Commandant’s wife and family, their socialising with the handful of other middle-class ‘free’ inhabitants, the army officers and the medical officers. On the periphery, prisoners and convict servants and their children are a constant presence, sometimes threatening, sometimes almost out of sight – but never out of mind. Domestic scenes and private conversations are conducted as if there are eavesdroppers, as indeed there often are. ‘A sort of Cranford at More-ton Bay’ was the way Anderson described this novel, highlighting the grotesque contrast between floggings and murders, and scenes of genteel social life.

Anderson published some fifteen short stories and novellas, eight of which are collected in the 1987 volume, Stories from the Warm Zone and Sydney Stories. The five ‘stories from the warm zone’ are autobiographical fictions set in the Brisbane of her childhood, and, if they are a reliable guide, that childhood was serene, affectionate and materially secure. Born in 1916, Jessica was the youngest of a family of four. Her father was a stock inspector, and both parents were politically radical and encouraged intellectual independence. She grew up in suburban Brisbane, attending the State High School and the Technical College Art School. When she was only sixteen her much-loved father died. At eighteen, she left home. She landed in Kings Cross, ‘the only Bohemian centre in the whole of the country’ in the 1930s. There she lived in one of the old houses at Potts Point so lovingly described in Tirra Lirra, with Ross McGill, the man she would marry when she was twenty-three. He was a commercial artist, and she earned an income writing for magazines – formulaic stories, always under pseudonyms. They lived and worked in London for several years, returning to Sydney in 1939. Her daughter Laura was born in 1946. Jessica and Ross McGill divorced, and she married Leonard Anderson in 1955.

It was only during her second marriage, which ended in 1976, that she had the time and security to turn her hand to the serious fiction she had always intended to write. Now, as well as her own novels, Anderson was writing for radio – four original plays, as well as adaptations from Charles Dickens and Henry James. The legacy of this work in radio can be seen in her skilful use of dialogue to convey the tensions and nuances of relationships. Anderson’s admiration for James is evident in her attention to the uses of power, and the power of money. Henry Green was one of her favourite writers, and Muriel Spark another.

Anderson said that she felt little affinity with other Australian writers and the documentary fiction which she felt predominated in the 1960s, but that Christina Stead, in writing about Sydney, gave her courage. There is surely a tribute in Tirra Lirra to Stead’s For Love Alone (1944) with its heroine Teresa walking and waiting, dreaming and making embroideries, desiring to escape to some wider life. The difference between the two writers is evident in Anderson’s distinctive prose, with its perfectly gauged use of significant detail, as in this account of the adolescent Nora:

I carried my pale face, my dropped flag of ashen hair, my abstracted eyes, my damp concealed body, along the rough roads and streets, and across paddocks and vacant lots and playing fields ... Our suburb merged with farms, and by day, overtaken by a farmer’s cart, I would see the whip flick the horse’s rump and the shadow of the cart draw away from a shining pile of excrement. On certain hot nights scents and stench would mingle, frangipani and lantana with the wake of the night cart. I walked and walked, sometimes with an objective – a friend’s house, a shop, the church or school – but mostly at random, to outrun oppression.

The girl’s longings, the young woman’s disappointments, and the pride that forbids her from admitting to either, are so memorably dramatised that Tirra Lirra by the River echoes in the mind long after reading. And this is no generation-specific experience, as Sally Pryor’s obituary for Anderson in the Canberra Times testifies. Born a year later than the book, she was given a copy as a teenager by her mother. Rereading the novel not so long ago revived the shock of recognition she had felt when she first read it, and also showed her new things that resonated. She was left wanting to know more about the author, ‘just what kind of woman she was, to have written such a gleaming, multi-layered story’. Jessica Anderson valued her privacy and let little be known about herself; yet there is a place for a biography that could tell the story of her life in conjunction with an account of the art of her fiction.