- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The pretext of this book is as simple as it is delightful. In 1982, at the ripe old age of nineteen, Sandy Mackinnon found himself on the windswept island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland. Iona is one of those places, familiar in the world of spiritual tourism, that is layered in irony. In ancient times it became home to a community of monks, most notably St Columba, for the simple reason that nobody in his right mind would follow them there. Now, of course, it is a popular destination for those who value more than their right minds. Iona, like Santiago de Compostella, has a small but cogent literature of its own. It weaves a spell. There is very little to buy there. It creates debt in other ways.

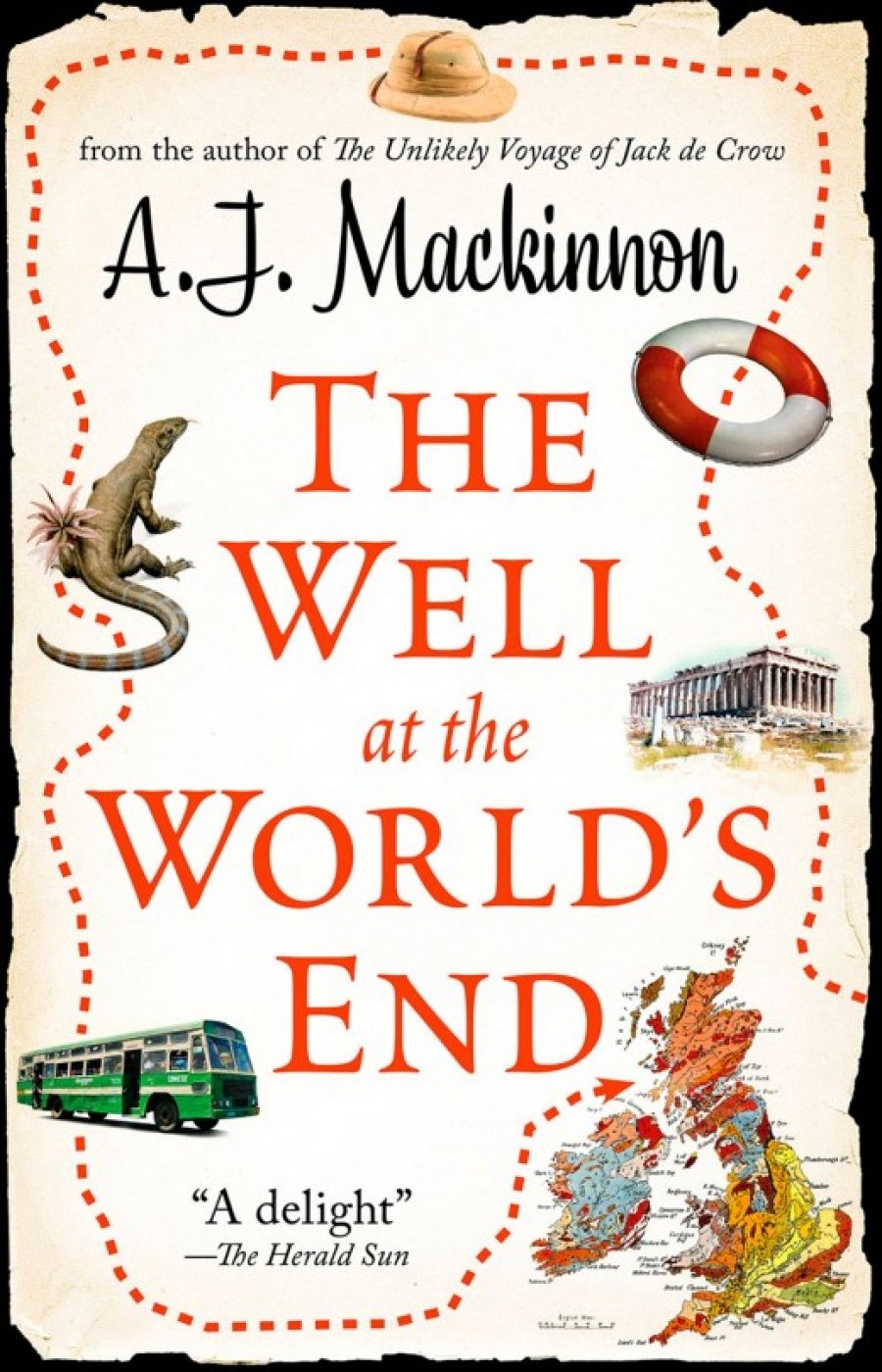

- Book 1 Title: The Well at the World’s End

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.95 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/aam1Q

This is the story of his return, a journey undertaken some eight years later. By this time, Mackinnon happens to have a plane ticket to New Zealand and takes leave from his job as a school teacher. Having reached New Zealand, he vows to get back to Iona without leaving the surface of the planet – in other words, by land and water. Mostly water. Mackinnon wants a slow trip, and he gets it. Months after setting out, he is still in New Zealand, still trying to cadge a ride on a yacht. It takes him half the book to get as far as Singapore. It doesn’t matter. Mackinnon finds life in boredom and adventure alike. He never makes the mistake of trying to explain his eccentricities. He has a penchant for magic tricks, The Lord of the Rings, mathematical abstraction, inventing board games and the fiction of Mary Stewart. It all comes in handy.

Mackinnon’s previous book, The Unlikely Voyage of Jack de Crow (2009), tells of his stop-start voyage from one side of Europe to another, starting with canals in England and ending at the Black Sea. On that journey, he made use of a tiny sailing vessel called a Mirror which he had found discarded; he describes it as the nautical equivalent of a Volkswagen Beetle. The little boat becomes a kind of dream machine for a bloke whose imagination has been fed by everything from Tom Bombadil to Malory to Captain Cook to Doctor Dolittle.

The Well at the World’s End is in the same kind of emotional territory: the resilience of a foolhardy dream in the face of an uncooperative reality. Lots of funny things happen over the twelve months neatly spanned by the book, and many of the characters are so improbable they could only come from reality. There are some wonderful set pieces, not least a glorious series of misadventures while trying to cross the Laotian border into China. Here, Mackinnon encounters an official whose English is impressive in all regards other than pronunciation. It takes Mackinnon a while to work out that ‘anted ully gully’ means ‘entered illegally’ and that ‘white plus’ means ‘wait please’. No less diverting is his disorientation within the labyrinth of Mont St Michel. Elsewhere, he falls in with a New Zealander who was saved from suicide by giving a lift to a hitchhiker and is so grateful that he now spends his life driving other hitchhikers wherever they want to go, showing them the shot gun he never used. And so on. Mackinnon feasts on the human condition. He enjoys a moment, in a yacht race, in which an Indonesian village leader pays little respect to a judge and naval officer but is mightily impressed to have a teacher come to visit.

The most soulful humour of this book comes from a richer place than the land of funny stories. It comes from the author’s insistence on finding his feet within a fantasy which the facts of life are always trying to steal from under him. Mackinnon’s studied naïveté is superb. He chooses innocence in the face of experience. But there is also a loneliness here. Mackinnon does forge bonds along the way. He strikes up a rapport with a schoolboy called Peter, whose education has been taking place at sea for three years. Towards the end, he teams up with a chum called Newton, and the pair put up with each other reasonably well. Yet Mackinnon is essentially a solitary traveller. Like many of literature’s solitary travellers, he makes great company. You find him in a lot of escapades, but he keeps parts of himself below deck. He always gets away.

Comments powered by CComment