- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Needless to say, yet needing to be said, Australia’s twenty-third prime minister, R.J.L. Hawke, emerges from this interesting, sometimes engrossing yet disconcerting book smelling like roses. When MUP decided to publish, it must have seemed like a good idea. Deployed on television, Bob and Blanche were a marketing dream. But the result has a fatal flaw; it neither enlarges Hawke as a political leader nor advances d’Alpuget as a writer.

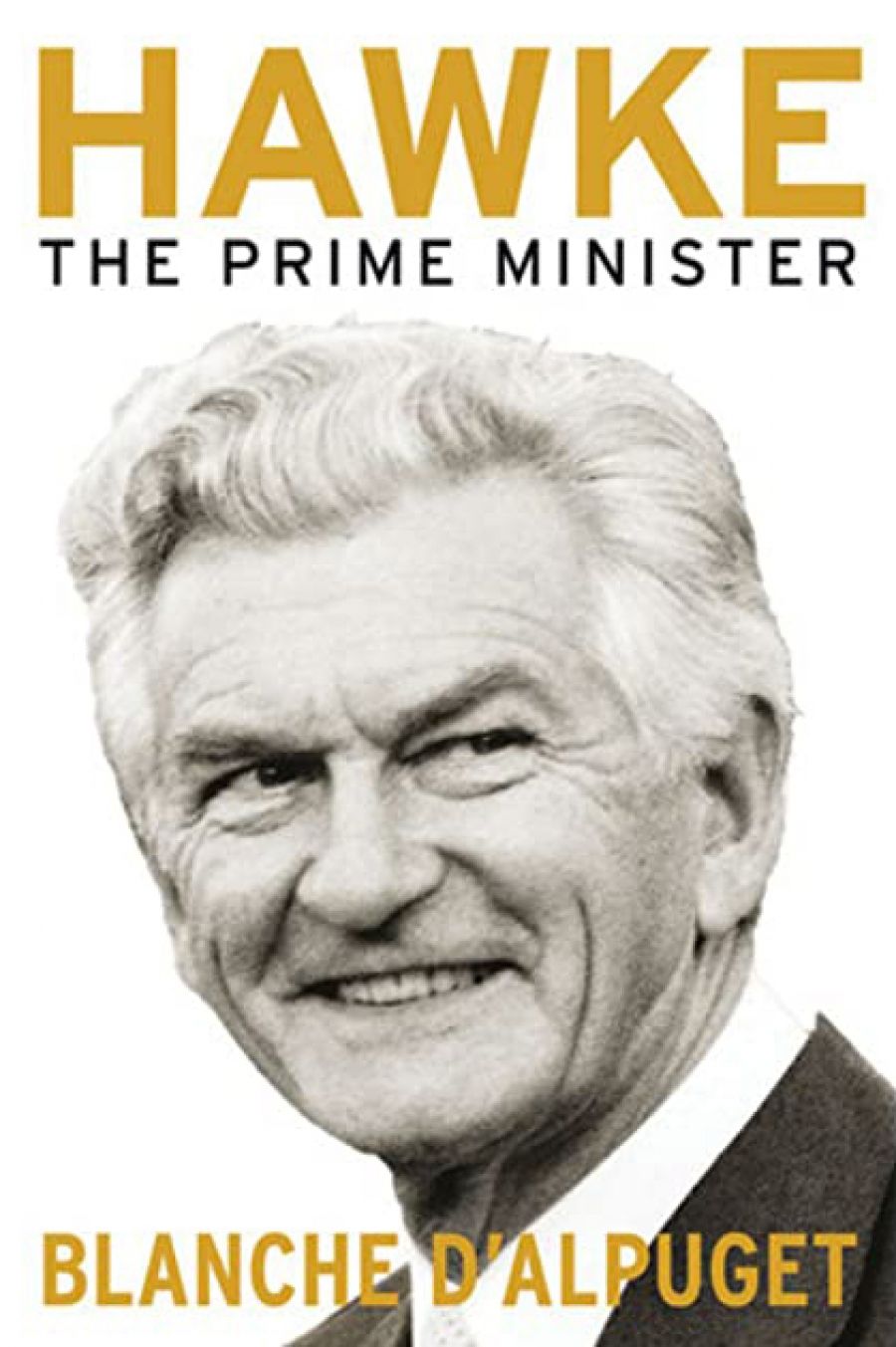

- Book 1 Title: Hawke

- Book 1 Subtitle: The prime minister

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $54.99 hb, 401 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zJA0r

Together, however, their positive qualities neutralise, even negate, each other, blending in a mix that is at best tantalising and, at worst, embarrassing. D’Alpuget strains at melodrama, presenting her lover, now husband, as not just another Australian prime minister but as a figure of mythology, born, as his mother believed, to fulfil the prophecy in Isaiah that ‘the government shall be upon his shoulder’ and compelled throughout his political career to obey the iron law of heroism.

Describing Hawke’s fraught relationship with Graham Richardson, one of the hard men of the New South Wales right faction, she writes: ‘But Richardson, for all his earlier hero worship of Hawke, did not understand what a hero is, nor what a hero does. Throughout history, and in every culture, the hero cannot surrender. He will fight and die for his beliefs.’ Or, at a slightly lower level of reality, dealing with relief from the pressure in government of hard work, Hawke could ‘always … tune himself into the glorious, exhilarating sensation of holding in his hands the nerve fibres of historical action’. When d’Alpuget seeks Hawke’s motto for Australia, it is that of the Roman Emperor Hadrian: ‘Humanity, Liberty, Happiness.’

D’Alpuget is searching beyond Australia for a model for her hero, who is in love with everything Australian. There is a one-page snapshot of Australia’s capital in the 1980s, Canberra and ‘some paddocks’, its roads ‘as smooth and as charcoal grey as a diplomat’s suit’, socially liberal (legal marijuana for private use and Australia’s distribution hub for pornography) and the mentality of a colonial outpost, with sahibs and memsahibs, including the press gallery, ruling the roost. She describes Hawke as ‘the wily new sultan’ who has ‘snatched the throne’ without pukka permission.

She has said that their love affair will live on when they are dead. But not in this form, as an adjunct to politics. We do not know why or how they love each other. We do not know what happened to Blanche after Hawke decided to drop her (in what today’s spin doctors would call ‘the national interest’, but she describes more modestly as the greater good of becoming prime minister, reasoning that a divorce was not a good look) and then, when that was over, embrace her again. An opera perhaps?

D’Alpuget conveys her intimate knowledge of Hawke in telling observations: ‘Few understood that Hawke’s emotional softness, his tendency to tears, his habit – maddening to staff and colleagues – of wanting to listen to the stories of ordinary Australians, was the saving balance in his character, a humility without which his alpha-male swagger would have made him unbearable.’ She notes that Hawke had been a Sunday school teacher and student preacher: ‘Christian principles were in his bones and he found their expression not in lifeless Sunday ritual but in the vibrant, communal, morally cohesive and uplifting labour movement.’

We are reminded that several Labor leaders are from religious families. Hawke’s lifestyle, and immersion in the capital–labour intricacies of the secular state and marketplace, meant that he abandoned his background more dramatically than most, but he continued to believe in the ‘one big truth’ of moral, as well as material, progress. His virtue with caucus, however, which was a ‘nest of envies’, was that the Australian people ‘loved’ him (d’Alpuget likes the word and uses it often). He was ‘Mr 75 per cent’, the most popular prime minister yet. Why they did love him (and why they loved Kevin Rudd almost as much) is one of the mysteries of Australian mass psychology that psephology is yet to reveal.

D’Alpuget’s portraits of contemporaries are often delicious. John Button was ‘a droplet of a man, a thimble of wit, vitality, charm and scepticism … as a university student … wildly popular for his knowledge of scores of dirty songs, and, according to Hawke, the most consummate liar he ever met in politics’. And of David Combe: ‘a tall, gangling man with a mop of black curly hair and a personality so open, so hearty, so expansive, so obviously good-natured, so essentially innocent, he put one in mind of a huge puppy.’

She disposes of Paul Keating as a sharp-witted bovver boy of the New South Wales right, ‘with a good dose of Johnny Rotten up his well-tailored sleeve’, who had ‘in his bones’ the ‘Irish Catholic anger of how it hurt to be pushed to the margins of society’, and who fancied, as compensation, the antiquities of France’s Second Empire. She points to the Plácido Domingo speech as evidence not only that Keating considered the Spaniard superior to Hawke’s ‘favourite tenor, the lovable fat Italian, Luciano Pavarotti’, but, the even greater sin, that he despised Australia, as shown by his description of John Curtin as a ‘trier’ and Chifley as a ‘plodder’. With the passages on Keating, as often in the book, it is hard to know whether it is Bob or Blanche speaking. She quotes ‘an observer’ to point up the difference between Hawke and Keating: ‘If somebody was nice to Bob, he thought that person liked him. If somebody was nice to Keating, Paul thought, “What’s he after?’” John Bowan, Hawke’s foreign affairs adviser, is the authority for ‘a mixture of a hired killer and someone you could imagine as a parish priest’.

Hawke’s falling out with Graham Richardson is told as a tangled web of moves and offers involving the cabinet post of Transport and Communications and the diplomatic post of high commissioner in London, but the key seems to have been what Hawke’s friend Peter Abeles told the prime minister about Richardson, and this is not revealed. The author relies on Marian Wilkinson’s The Fixer: The untold story of Graham Richardson (1996) for her comment that Richardson ‘seemed fascinated by gangsta chic’.

An unexpected talent for political journalism provides value, enlisting the testimonies of witnesses who worked with Hawke in various ways: Peter Barron, Mike Codd, Ross Garnaut, Geoff Walsh, Hugh White, and Richard Woolcott. They provide weight to the projection of Hawke as a prime minister who was both shrewd and innovative. His slogan ‘enmeshment with Asia’ is emphasised. His launching of the forum Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 1989, when the Americans were upset at being initially left out (with Taiwan), and the economic summit, which brought capital and labour together when Australia was threatened with being ‘the poor white trash of Asia’, are explored. (The Accord, which seemed at the time to be Hawke’s idea, is attributed to Ralph Willis.) Not much is made of the defence changes effected by Paul Dibb and Kim Beazley, which helped to liberate Australian foreign policy from its dependence on the United States and which accounted for Gareth Evans’s hyperactive period as foreign minister. Indonesia, which became a special interest of Paul Keating, is largely ignored.

The political fallout in the Labor Party from this book will presumably continue, especially as it affects Paul Keating, who believes he was the spine that gave the Hawke government intellectual rigour. It won’t help Labor in its current leadership predicament; the evidence of ‘leaking’ from rival camps in the Byzantine world of Labor politics is well documented. It is one of the curiosities of Labor luminaries that their reflections are more damaging to their party rivals than to their political opponents.

Bob Hawke still awaits his definitive biographer, and the great love story still waits to be told.

Comments powered by CComment