- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

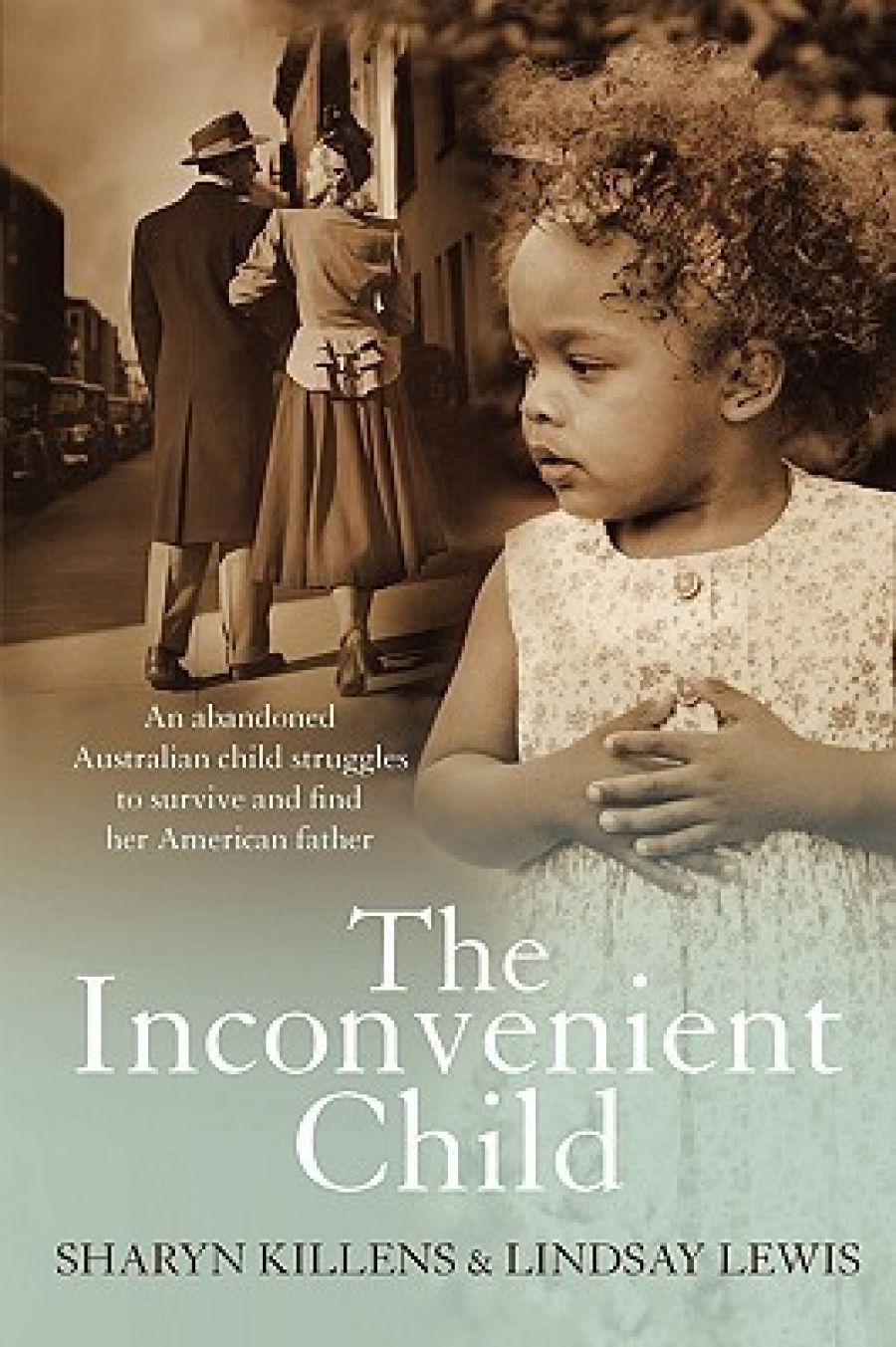

Sharyn Killens is no stranger to the spotlight. After a long career as an entertainer, she is used to appearing in make-up and gown, pouring out a song. She is also a veteran of interviews and media stories, with a different song: that of her own extraordinary life. In The Inconvenient Child, written with her friend Lindsay Lewis, Killens (known on the stage as Sharyn Crystal) relates a wrenching and finally satisfying story of abject misery and triumphant emotion. In the paradigm of classic Australian memoir, her tale needs no bells and whistles to ring true. It is a transfixing performance.

- Book 1 Title: The Inconvenient Child

- Book 1 Biblio: Miracle Publishing $24.95 pb, 416 pp

There are three main elements to Killens’s story, each of which is sufficient to make a compelling memoir. She was the product of a two-week fling between a blonde good-time girl from the suburbs and an African American Marine who visited Sydney following World War II. After the Marine’s departure, a small, inconvenient brown baby was born. ‘Princess Mummy’ gave the child away: first to friends, then to a convent where she was beaten by a psychopathic nun, and finally, when Sharyn was a frustrated, naïve teenager drawn to the lights of Kings Cross, to the infamous Parramatta Girls’ Home (a kind of remand centre for ‘delinquent’ girls). She ended up in the even more terrifying Hay Institution, which was little short of a maximum-security, hard-labour prison. The chapters devoted to this period are deeply disturbing: the girls were re-programmed with enforcements such as being forbidden from moving while asleep, never making eye contact with other people, being required to display their used sanitary napkins, punishing exercise and labour regimens, and bread-and-water isolation in freezing cells. Killens tells it bluntly and relentlessly. For the horrors and national shame contained in this part of the book alone, it deserves a wide readership in Australia.

Drugs, booze, bad relationships and self-destruction followed for the lonely young woman on her release. A black girl in a white world, rejected by her mother’s family and damaged by her ordeals, she nevertheless found her way first into a stripping job and then as a singer. ‘What a perfect career for a child who just wanted to be loved, feeling all that love flooding across the footlights!’ she exclaims. Killens is proud of her career and of her transformation into a glamour-puss prowler of clubs and cruise ships, but details of the Sydney nightclub entertainment world may not interest everyone. She describes the stuttering yet determined trajectories of recovery vividly and honestly, and sets the stage for the dénouement of her tragedy-to-triumph story.

The author’s longing for her father has been a constant in her life, despite her mother’s adamant claim that he was dead. It was only later in life that she could begin to track the long-vanished Marine, and the possibility of American relatives. The contrast between her mother’s complacent petit-bourgeois cruelty and the warmth of the people she finds in the United States is made with evident relish. This is a tale that portrays almost inconceivable neglect and spontaneous human sweetness with understatement but full feeling. The theme of Killens’s relationship with her mother is particularly agonising, as each woman determinedly pursues her object: Killens to grow closer to the parent whose love is always retreating; the mother to keep a distance between herself and the child she basically disowned. Though race issues are not examined in the same depth as in Dreams from My Father (2010) by Barack Obama – another mixed-race memoirist searching for his father – there is no doubt in the narrator’s mind that the rejection was all about the colour of her skin.

Courteous phrasing and palpable rage inform the depiction of the Princess Mummy, but Killens is frank about her own disturbed behaviour, her failures as a parent and her anger. The narration leaves adequate critical distance for the reader to judge the author, even as it keeps a personable clutch on our sympathy. But the emotion flows as Killens finds a different sort of family, the headiness of media attention and, finally, the self-belief that had been forfeited during the long ordeal of her life.

This is undoubtedly a ‘misery memoir’ in many aspects, but it transcends the tragico-porn of the genre. The story is almost trite in its extremes, its fairy-tale dimensions, its classic tropes of lost child and dysfunctional damaged misfit. Its authenticity comes from the specifics: just how it feels to strip paint off a wall with a wire brush, a bucket of water and a brick (an initiation ritual at Hay), or what it feels like to do a hundred push-ups before breakfast on an icy morning; what Killens’s son said at the moment she realised she was in danger of becoming a heroin addict; the tellingly different ways that she and her mother take their Scotch, as Killens pushes once more for her father’s name after a carefully engineered cosy evening – and from Killens’s personality, which impels the narrative with exclamations, admissions, candour and the fulsome energy that has seen this exceptional woman find the safe home she was always seeking. A brave and moving story, well though not ostentatiously told, The Inconvenient Child reminds us that even the princesses of fairy tales must fight for their crowns.

Comments powered by CComment