- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Dance

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

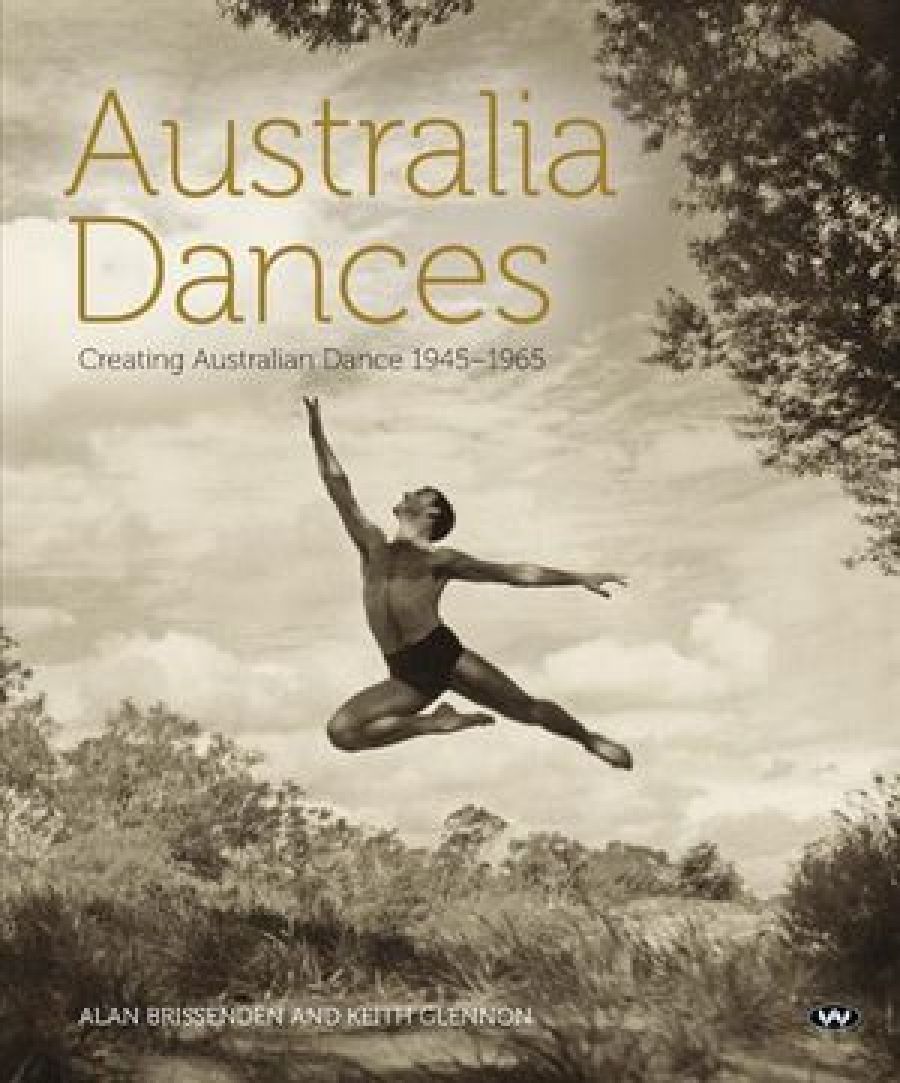

Dance is an ephemeral art. This is just one reason, among many, why Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon’s beautifully designed and presented Australia Dances: Creating Australian Dance 1945–1965 is an important contribution to the light industry of dance historiography. Its eye-catching cover, with a Walter Stringer photograph of dancer William Harvey in a soaring leap above an Australian landscape, will attract bookshop browsers. A perusal of its contents will encourage purchase, as a special gift or for one’s personal library.

- Book 1 Title: Australia Dances

- Book 1 Subtitle: Creating Australian dance 1945–1965

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press $70 hb, 270 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/95v64

The standard of dance photography is particularly high in Australia, and examples by the too-little recognised Stringer, and others lesser known, generously support the text. Most of the images are from the Barr Smith Library archives of the State Library of South Australia. Such was the wealth of available material that it must have been a prodigal nightmare for designer Liz Nicholson. Sometimes, though, the number of smaller photographs to a page seems to overwhelm the text.

Australia Dances has had a gestation of nearly fifty years. It was begun in the late 1950s. An economic recession overtook a contract to publish. Brissenden brought the book up to date while he was teaching at the University of Adelaide. Glennon died in 1983, and it was not until Brissenden retired in 1994 that the project was finally prepared. Wakefield Press has published the book to its usual high standard, with a number of private citizens contributing to the cost of production.

An introductory chapter gives an overview of the period. When the pair began interviewing and witnessing, collecting and writing, there were no permanent dance companies in Australia. How much has changed. The first three of the fifteen chapters deal with the most influential companies of the period: Borovansky Ballet (1940–61), National Theatre Ballet Company (1949–c.55) and the fledgling Australian Ballet (1962). Chapters are then devoted to each of the states, and one each to Modern Dance city by city and Ethnic Dance (including Aboriginal Theatre). The final three chapters look at Training Organisations, Examining Organisations – so much a part of the Australian dance scene – and Eisteddfods. There is a two-page listing of resources and an excellent index.

The decades between the world wars built on the legacy of pioneers such as Hélène Kirsova and Gertrud Bodenwieser, and members of the Colonel de Basil Ballets Russes who had remained at the conclusion of the 1939 tour, Edouard Borovansky and Kira Bousloff among them. When de Basil’s third company to tour eastern Australia left our shores in September 1939, ten per cent of the company remained behind. Australia was a safe haven, especially for those whose passports were no longer valid in a Europe facing imminent war. The company also left behind a huge appetite for classical ballet in the Russian tradition. Talented and entrepreneurial artists had fertile opportunities in which to further their art.

Kirsova had stayed in Sydney after an earlier de Basil tour and founded the Australian National Ballet in 1941. The company folded after she, intent on preserving her independence, refused the backing of J.C. Williamson Ltd, which then supported the Melbourne-based Borovansky.

Bodenwieser escaped the Anschluss in Vienna (her husband did not, and died in a concentration camp) and arrived in Australia via South America, in 1939. Her central European approach to modern dance has been most influential in Australia.

Borovansky and Bousloff, like Kirsova and Bodenwieser, were inspirational, often autocratic, leaders. Bousloff, with her husband, James Penberthy, established the West Australian Ballet in 1952. They balanced new work, often with Aboriginal themes, with modest stagings of the classics. West Australian Ballet is now a flagship company for the state and is the longest surviving professional company in the country.

The Borovansky Ballet formed, disbanded and re-formed a number of times, and took classical ballet to all parts of the Commonwealth. Its repertoire was the classics; there were few original works. There was employment for dancers, but little for composers or choreographers.

Of the forty works presented, only four were set to compositions by Australian musicians. There was only one Australian-born choreographer, Dorothy Stevenson, one of the two women to whom this book is dedicated; the other is Laurel Martyn. Stevenson’s Chiaroscuro was one of the most important events in Borovansky’s 1951 twelve-week Jubilee Season in Sydney’s Empire Theatre. It was sandwiched between Act Two of Swan Lake and La Boutique Fantasque.

In all that time, only seven artists created original designs for new ballets. This is one of the attractions of the book. It is lavishly illustrated with set and costume designs, many in colour, by William Constable, Elaine Haxton and Kenneth Rowell. The authors write: ‘A revival cannot develop an art or an artist in the same way that a new work can.’

Throughout the book, there are illustrated summaries of notable productions by various companies. This offers a valuable, if tantalising, snapshot. The key artistic figures are noted (though rarely is the lighting designer), there is a summary of the content and an evaluation of the performance. There are also pen-portraits of the leading personalities, especially those concerned with modern dance.

There are not that many books on Australian dance; this is one of the most comprehensive, even-handed and visually appealing. Perhaps uniquely, the authors have seen almost all of the productions chronicled in the book.

Comments powered by CComment