- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

World War I is lodged in the minds of Australians with mythic power. Chris Womersley, in plain and startling yet tender and lyrical prose, has constructed a moving narrative that opens up the wounds of war, laying bare the events that pre-date the conflict and reach forward into the collective memory. I was reminded of A.S. Byatt’s recent novel The Children’s Book (2009), which also foregrounds in poetic language the Great War and etches forever the horror of broken bodies and minds on the consciousness of its readers.

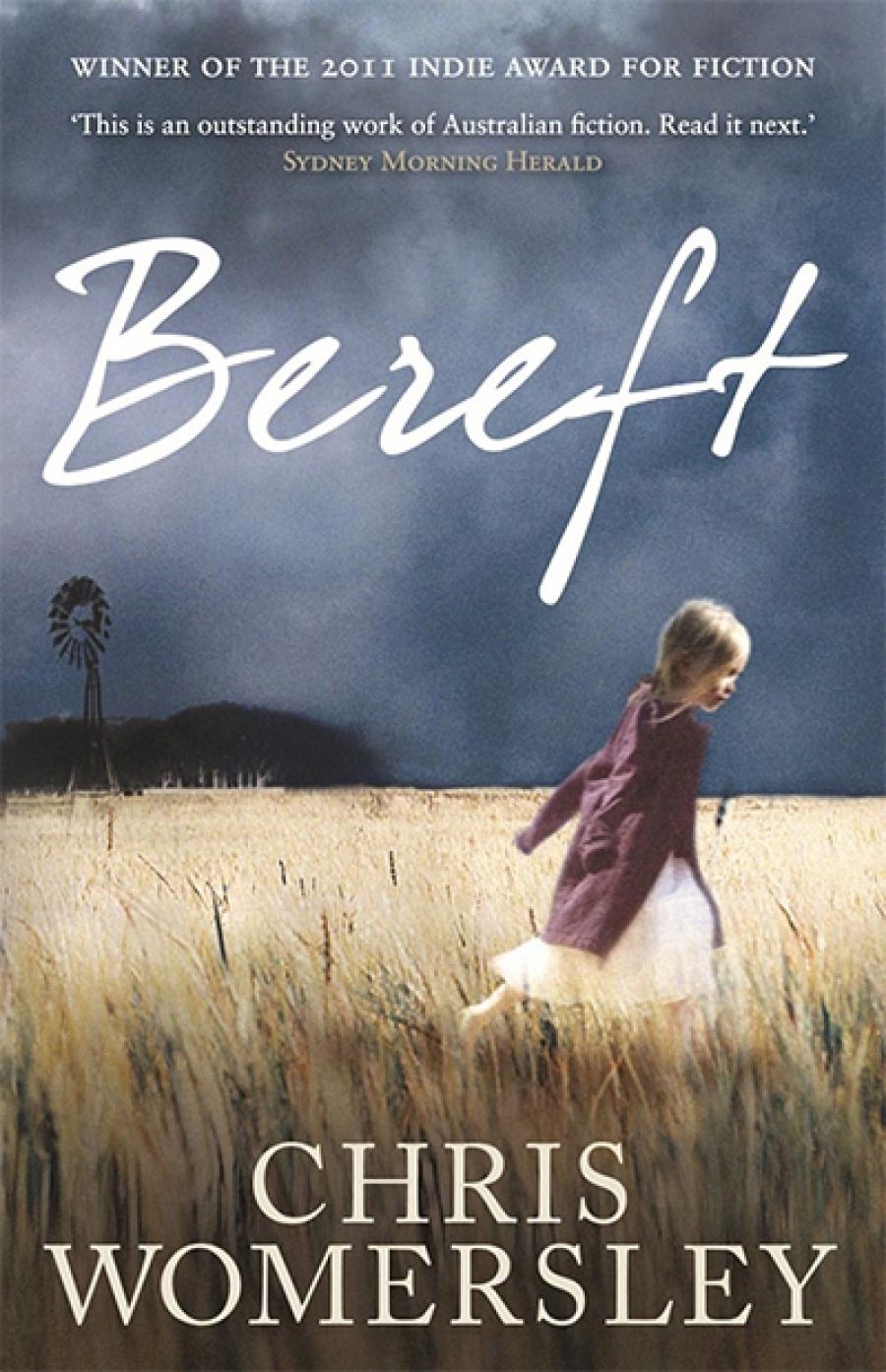

- Book 1 Title: Bereft

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.95 pb, 276 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/aEb9q

Bereft is the story of how Quinn may have survived the war and returned home after all, like a living ghost, when his mother was dying, and how he took revenge for his sister’s murder and for his own disgrace and ruin. His elusive presence in Flint in 1919 takes on, for the people remaining in the little town, the ‘shimmer of truth’. Such a shimmer plays across the novel, drawing the reader into the broken-hearted world as it emerges from the meaningless carnage into a chimeric peace. The war, with its mythic qualities, takes on the qualities of a hideous dreamscape; the fact that hallucination is never far away adds to the breathless nightmare nature of the story. Sometimes I detected a faint echo of Under Milk Wood, though nothing whimsical, about Bereft. This is an account of terrible cruelty, of profound and wrenching sorrow. War is the big drama of human horror, but the basest acts of cruelty are also enacted in what passes for peacetime. That Womersley can marry these two extremes, and construct a narrative in which the reader is left with a burning sense of regret and tenderness, is a mark of his skill and of his fictional reach.

Quinn, on his secret return home in 1919, inhabits the wild places in the hills behind Flint, leading a fugitive existence, with stealthy visits to his dying mother. One time he takes her a bunch of lavender, a herb known for its power to induce drowsiness; later she is unsure whether she spoke to her son or just imagined doing so. The reader is frequently placed in a similar position of doubt, but this effect only increases our desire to believe and strengthens the credibility of the supernatural element in the novel. Quinn has visited a London medium and come away with a written message from the spirit of his beloved sister Sarah: ‘Don’t forget me. Come back and save me. Please.’ This note is his treasure and his talisman. Truth is a sombre, fragile matter.

Into Quinn’s life in the wild comes a strange elfin companion, a twelve-year-old orphan sprite named Sadie Fox, who is looking for her brother, ‘a pilot in the war’. Quinn and Sadie have, in Quinn’s own words, ‘conjured each other’. They are each of the earth, having the ability to listen to the deep sounds of the natural world. Quinn constantly compares the busy lives of insects with the lives of human beings, and he can detect the ‘grinding of the earth’ as it revolves in space. It is a world forsaken by God, where, in a moment of Blakean symbolism, Sadie kills a sacrificial lamb.

Quinn’s quest for revenge moves relentlessly on with the tension of a thriller, propelled by Sadie’s dream-desire to accompany him to Kensington Gardens, where there is a ‘fairy queen and she grants wishes’. Quinn concedes that this would be a fresh green place filled with mist. Thus the link to Byatt’s The Children’s Book becomes obvious. In both novels, the stench and gore and mud of war are played against the sad narrative of Peter Pan and the fairies, articulating the inability of human beings to imagine anything more useful than fairyland. At the story’s close, Quinn and Sadie and a grey horse walk away on an ‘ordinary Sunday morning’, to the accompaniment of hymns floating from the church. The reader can only mourn them and the suffering of the foolish world.

Comments powered by CComment