Over the years the popularity of short fiction has fluctuated greatly, for mysterious reasons. A senior publisher once told me that publishers loved short fiction collections but that the reason they rarely published them was due to booksellers’ reluctance to support them. When I put this to a major bookseller, they claimed it was the other way around.

Since writers keep writing stories, perhaps the blame lies at the feet of readers? Or certain types of readers. Conspicuously, these three new collections come from independent publishers whose readers are unlikely to be found browsing the shelves at Big W. But they all contain such strong examples of the form it is hard to see why it seems continually under threat.

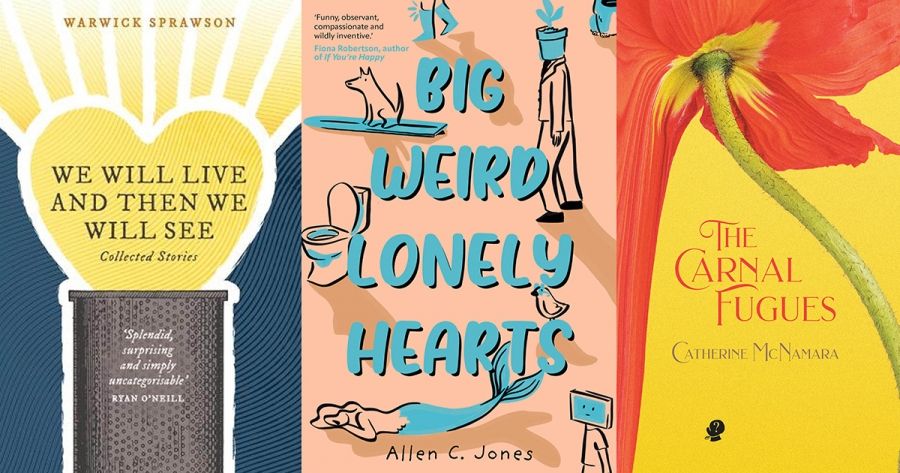

Warwick Sprawson’s first collection, We Will Live and Then We Will See, delivers a standout in its title story. Set in Russia and slyly exploiting perennial misinformation about the death of Vladimir Putin, it focuses on a presidential double, who is an unwilling conscript as his official stand-in. The story’s relevance was reinforced when news of Alexei Navalny’s death shocked the world, yet it maintains a light touch, allowing its full horror to sink in via implication. ‘Bouzouki’ recounts a history of interactions with an elderly Greek neighbour in a restrained, almost bland, narrative voice that controls the emotions yet allows us to feel much.

While stories such as these reward rereading, some of the shorter stories suffer due to the very brevity they embrace. ‘A for Australia, A for Alive’ and ‘Heroes’ both end just as they become interesting; and ‘The War on Cheese’, while clever and funny, relies too heavily on one idea.

Overall, the collection is engaging and quirky although it sometimes flirts with the gimmicky. Alice Munro and George Saunders aside, no short story writer can achieve perfection every time, so it is unfair to expect total consistency across a collection, and Sprawson’s best pieces are extremely good indeed. If you get the sense that he doesn’t take himself too seriously, this is confirmed at the end: the author biography offering ten alternative short paragraphs is more suited to a student anthology.

There is nothing wrong in having fun with fiction. Allen C. Jones’s Big Weird Lonely Hearts, takes humour to another level: the entire collection plays with images, ideas, and language. Many stories negotiate arbitrary shifts of scene and action as Jones leaps from one surreal moment to the next, disregarding the fact that we might actually want to believe in the bizarre, not to mention care about his characters’ fates.

‘The Last Tiger in the World’ is an example of how readers will readily accept an implausible premise (as they do in Kafka’s Metamorphosis), but not if the voice is misjudged or the story tips into the preposterous. Here a child is told that her missing mother has gone to Paris when in fact she has been eaten by the tiger in her family zoo; it all works until the part about the tiger’s tail tasting like nougat and being shaved and sold as cotton candy (after which the story gets decidedly weird). Other stories concern a woman who discovers a clitoris on the back of her knee (not the most surreal thing in the story); a man who resembles a bush; a boy with a computer screen for a face; and an illegal immigrant mermaid.

Small doses: that’s probably the best approach for these random stories. Amid them is one that is so ridiculously compelling it almost eclipses the rest. Exploiting the classic trope of dog-cat enmity, ‘A Mexican Legend’ manages to be hilarious, inventive, silly, and utterly endearing. It is emblematic of the entire collection: everyone – or everything – just wants to belong, to be loved. Hence the collection’s title.

Perhaps the gravity of Catherine McNamara’s The Carnal Fugues is more marked by comparison with these first two books, but her stories are undeniably striking. A selection from three previous collections, all published in the United Kingdom, the book seems a bold punt for Puncher & Wattman, but it is reassuring to see such faith being invested in an author.

The first story is a strong start to the collection. Set on a boutique tourist boat in the Mediterranean, ‘Adieu, Mon Doux Rivage’ is memorable for its unpredictable characters and razor-sharp narrative voice: a man’s tattoos are described as ‘busty women who seem to be feasting upon his physique’. This is only on the second page. The rest of the stories (there are forty-two in all) feature diverse characters in diverse locations – London, Mali, Paris, Berlin, Athens, Verona – yet there is also a distinct thematic coherence in their focus on the ruthlessly transactional nature of relationships, a coherence all the more impressive given that the stories are drawn from three separate books.

McNamara’s characters, desperate and duplicitous, fuelled by illicit desires and poor decisions, are often unafraid to reveal their worst selves. The narrator of ‘Young British Man Drowns in Alpine Lake’ confesses to being aroused by his girlfriend’s history of sexual abuse. Another male narrator gets hard when he overhears his brother and fiancée fighting. Risk-taking is high on the agenda: ‘Hôtel de Californie’ is infused with tension as a man conducts liaisons that are ‘fragrant with doom’ in a country where homosexuality is forbidden.

Several stories are set in West or North Africa. In one of these, ‘The Cliffs of Bandiagara’, a journalist and photographer drive through Mali to visit a famous musician for an English magazine interview. Despite the self-interested and morally feeble adult characters, the story remains curiously non-judgemental thanks to a documentary style and shifting point of view. A dearth of personal names – ‘the boyfriend’, ‘the journalist’, ‘the boy’ – injects a fabulous quality to the story, yet the only lesson it might contain is that everyone has their secret agenda, even a child.

‘Magaly Park’, one of the few stories set in Australia, introduces a voyeuristic narrator ostensibly spying on a teenage schoolgirl. Unease dissipates as we learn that the narrator is her boyfriend, waiting for her mother to allow her a few minutes to meet him: ‘There are [days] when we sit like two old people who have no mirrors in the house because each is a reflection of the other.’ Amid their tender patience, neither wishes for any more intimacy than this.

The very short stories, or flash fictions, are accomplished, but their brevity cannot compete with the layered intensity of the longer ones. Like Sprawson’s, some end with a sense of frustrating prematurity. One of these, ‘The Mafia Boss Who Shot His Gay Son in a Beach’, is essentially encapsulated in the title. An exception is ‘Banking’, which, in less than three pages, charts the demise of a relationship and its accompanying acts of revenge with an ending that is neither too neat nor too ambiguous, allowing our imagination to supply the rest.

McNamara writes in arresting prose and uses vivid descriptive detail: an old, decrepit man has ‘towed his own body for years now’; another, younger more cocksure man, seems to his aunt to be glowing with a ‘strategic, masculine beauty’. Intriguing and cosmopolitan, her stories are infused with historical weight and a worldly wisdom suggestive of timeless, even epic, narrative. They also reflect a keenly observant, well-travelled life (McNamara has lived and worked in France and West Africa, and currently runs a writing retreat in Italy.) A serious reader disregards cover comments, no matter how glowing or prestigious, but Hilary Mantel’s endorsement of McNamara’s stories is thoroughly apt.

![]() Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..