- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: State of mind

- Article Subtitle: A whiplash tour of global crisis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Remarkably, Ukraine fought an effective, close-run defensive campaign and the war turned into a quagmire for Vladimir Putin’s regime. As early as the following month, with the appalling revelations from Bucha of Russian atrocities, it was clear that this was – as they all are – a very dirty war. At the time of writing, the frontline exists in precarious stalemate and serious questions loom about the reliability of ongoing US-led material support, which is necessary for Ukraine to continue the resistance.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

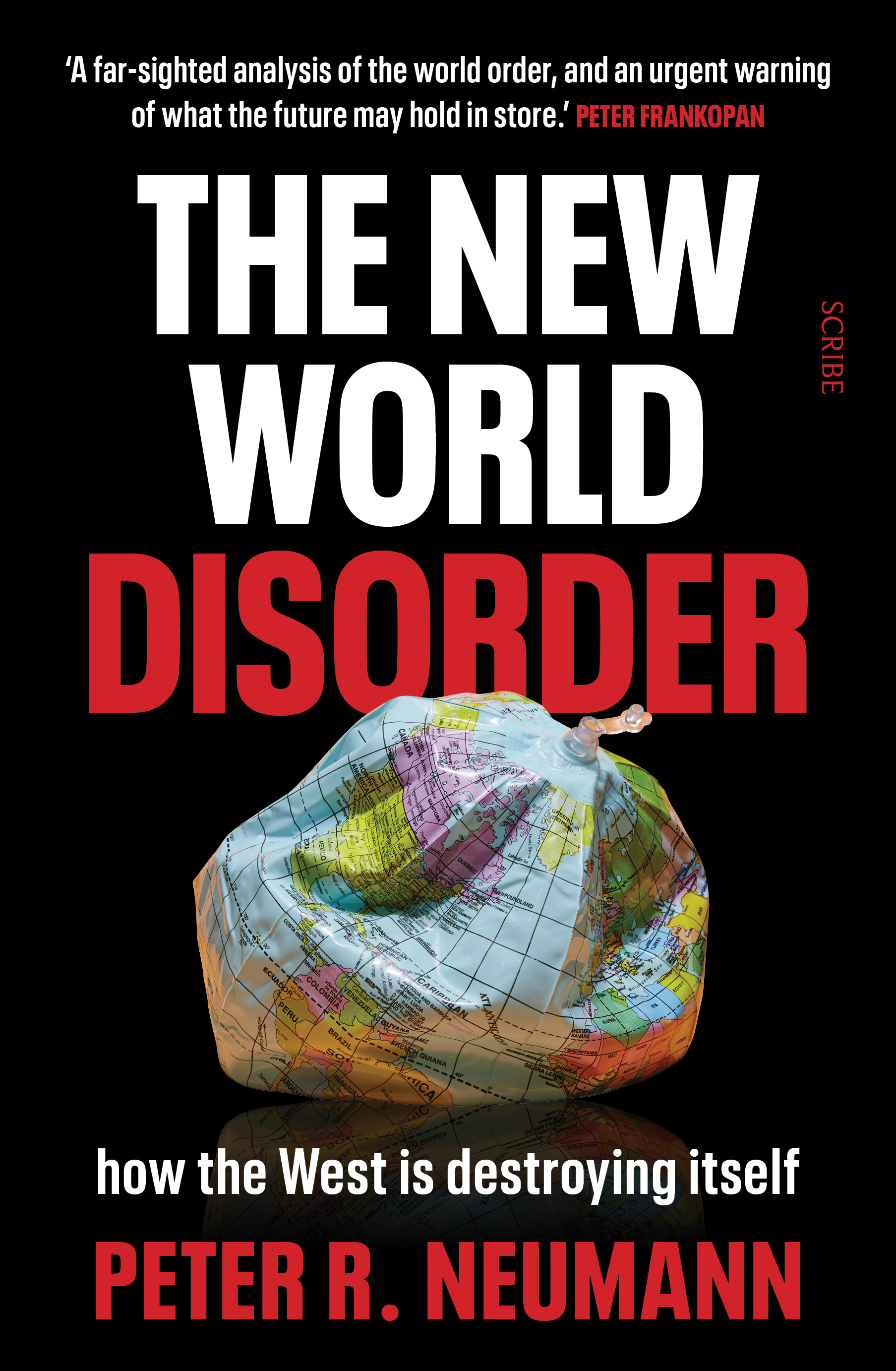

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): William Leben reviews ‘The New World Disorder: How the West is destroying itself’ by Peter R. Neumann and translated by David Shaw

- Book 1 Title: The New World Disorder

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the West is destroying itself

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $36.99 pb, 354 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For Peter Neumann, ‘the war in Ukraine has shown that many people want values-based politics, and that such a basis is what makes the implementation of joint policies possible at all’. It is not at all clear how the war in Ukraine demonstrates this: the argument is never elucidated. Nor is it self-evident that what is occurring in Ukraine offers much of a blueprint for ‘joint policies’ regarding any of the other core challenges facing the planet or the West. Unfortunately, unmoored comments or conclusions in this style are characteristic of this book.

People protesting in London against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 25 February 2022 (AdvancedPhotons/Alamy)

People protesting in London against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 25 February 2022 (AdvancedPhotons/Alamy)

The New World Disorder: How the West is destroying itself was first published in German in 2022. This edition is stamped 2024, with the translation completed last year by David Shaw. This is a book of commendable ambition, chronicling the unfolding ‘crises’ of the West since the end of the Cold War. It traverses engagement and the failure thereof with Russia and China, terrorism and the various Middle Eastern wars, financial crises, the internet, populism, and, fleetingly, climate change. It does not shy away from blunt assessments about various policy failures of American, European, and other Western countries and their élites, nor is it mum about their frequent hypocrisy.

It is, nonetheless, a frustrating book. Neumann, a Professor of Security Studies at King’s College London, begins by telling us that this is a book ‘about ideas and their (often unintended) consequences’. He tells us that ‘the West is neither a point on the compass nor a political alliance’, but ‘a state of mind’. The origin of that state of mind is identified in the Enlightenment, a set of intellectual and ideological developments that are then schematically set out in approximately two pages. It is therefore apparent from the beginning that the balance here between a sweeping scope and necessarily selective detail is uneasy, and a few concepts struggle to do a great deal of work.

Perhaps the chief shortcoming of the book is the absence of a clear approach to the ideas Neumann invokes: the Enlightenment, aspects of democratic peace theory, neoliberalism, and a range of others. Neumann seemingly sets this up deliberately. He marks out indicative schools of thought on ‘the West’ and its travails: the left-wing (Michael Lüders, Noam Chomsky), the liberals or ‘idealists’ (Heinrich Winkler, Niall Ferguson), and the ‘realists’ (Carlo Masala, John Mearsheimer). He eschews any one such approach, instead picking and choosing piecemeal from these traditions. This approach rests upon the assertion that ‘in many cases, the supposed interests’ have been ‘defined by values (“a united Europe”, “a democratic world”, “free trade”) to such an extent that the two [can] no longer be separated’.

Ultimately, though, this amounts to a squib, because no consistent or explicit approach to how values and interests interact appears. The question of power, how it is constructed and how it functions, lurks just beyond reach. The interests and influence of capital, for example, receive patchy treatment. The assertion that ‘the desire to spread modern liberal ideas has often been a sincere … concern of the West’ rarely meets a reckoning with how this ideological terrain might be shaped or conditioned by ‘brutal economic and power-political interests.’ This is evident, for instance, in the treatment of Western relations with both Russia and China over the past three decades. The relationship in the former between the ideologies of ‘shock therapy’ and the interests of financial capital are unclear. Similarly, a corporate thirst for market opportunities is strangely marginal in the telling of Western engagement with an ‘opening’ China under Deng Xiaoping and thereafter.

Climate change occupies an awkward position in the book; indeed, it seems possible that it was a late addition. In a brief final chapter, which is nevertheless re-emphasised in the conclusion, Neumann sets out a two-scenario dichotomy for the future, between ‘Climate conflicts’ and an ‘Energy revolution’, before settling blithely on the conclusion that ‘the most realistic’ scenario is ‘a combination of both’. So much is, by this juncture, surely obvious to anyone paying attention. Green technology and the long-run decline of legacy energy systems will not obviate deeper patterns of international politics, and the physical impacts of a warmed planet, to say the least, won’t help.

Once again, deeper questions are dodged. Neumann tells us that, as climate change progresses, ‘the West is destroying not just itself, but the entire planet’. But it is a gloss to say that the problem is the prevailing ‘economic and political model’. We know full well that the problem is particular forms of production and particular energy systems, in particular places under particular political-economic regimes: in the West historically, and especially since 1945; in coming decades more significantly in China, India, and elsewhere.

No digestible account that attempts to cover the interlocking challenges of recent decades can be without gaps. Nonetheless, more coherent accounts that incisively grapple with the relationship between various domains, and between the ideological and the political-economic, are available. Helen Thompson’s Disorder: Hard times in the twenty-first century (2022) comes to mind on geopolitics, climate change, and the energy transition. Adam Tooze’s Crashed: How a decade of financial crises changed the world (2018) came to mind when reading Neumann’s chapters on the financial crisis and European integration.

For an Australian reader, the occasional references to the antipodean role in all of this are sometimes recognisable, sometimes rather odd. The Howard government’s decision to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq is appropriately characterised as one driven by cynical alliance considerations, rather than by any enthusiastic subscription to the Bush administration’s ideological preoccupations. Australia’s performance on climate change is also rightly noted as poor, among sorry company.

Elsewhere, though, strange observations can be found. In his conclusion, Neumann summarises that ‘China’s “authoritarian modernity” has become the West’s main rival … even within parts of the West, such as in Australia and New Zealand’. It is difficult to make sense of that comment, on the grounds either of Australia’s domestic politics or of its international alignments, or indeed the 2021 AUKUS partnership.

Neumann is unapologetic in his refusal to prescribe a path forward. In the end, the follies and frustrations and tragedies parsed by this book are familiar and uncontroversial. ‘Honesty’ and ‘humility’ are cited in the final pages as necessary to move toward a more ‘sustainable modernity’, though it is unclear if these can function productively as political values. ‘A more sustainable modernity should avoid making lazy compromises with its enemies.’ This seems all well and good, though it is unclear what would constitute a ‘lazy’ compromise and who ought to be designated an ‘enemy’.

Without a clear-eyed diagnosis of how we all got here, it seems unlikely we will develop a clear-eyed idea of how to fix things – urgently.

Comments powered by CComment