- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Swimming between islands

- Article Subtitle: An awkward account of rescue

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

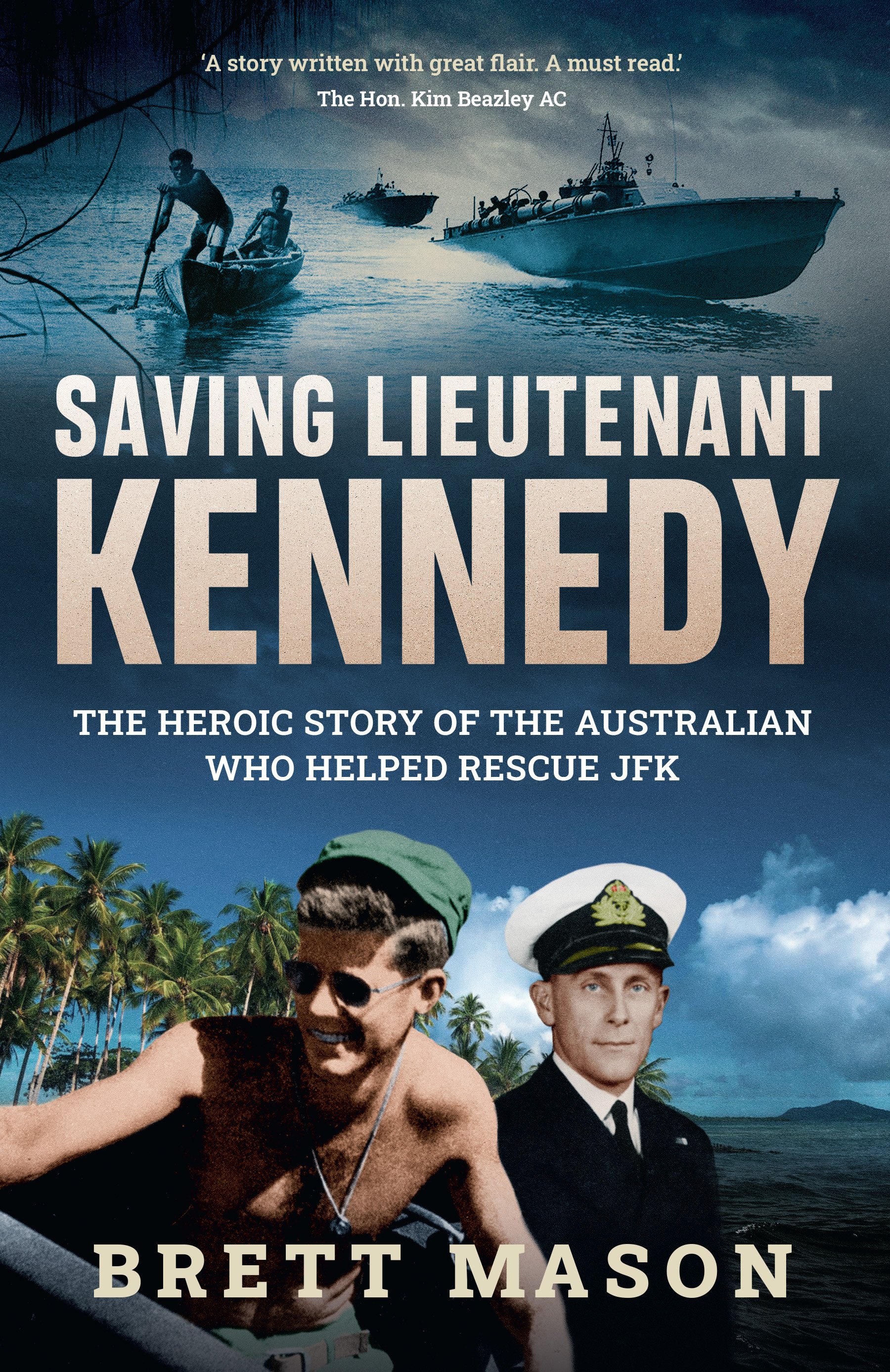

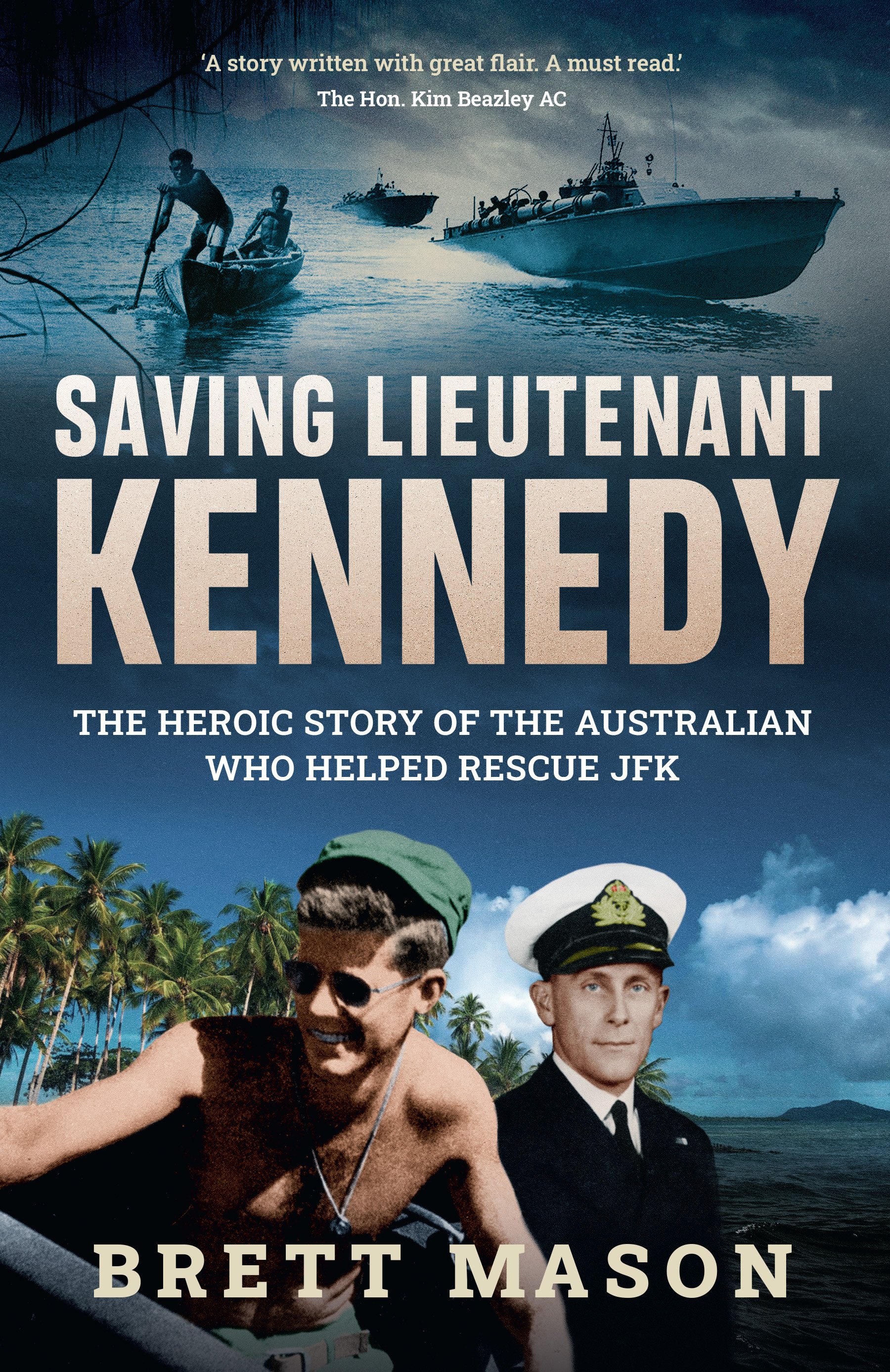

In August 1943, John F. Kennedy, then aged twenty-six, was rescued from the threat of Japanese captivity – or worse – by a few brave Solomon Islanders, in an operation coordinated by the Australian naval officer Reg Evans. Evans was one of the Royal Australian Navy’s ‘Coastwatchers’, intelligence collectors based perilously behind Japanese lines.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nick Hordern reviews 'Saving Lieutenant Kennedy: The heroic story of the Australian who helped rescue JFK' by Brett Mason

- Book 1 Title: Saving Lieutenant Kennedy

- Book 1 Subtitle: The heroic story of the Australian who helped rescue JFK

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 254 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This is Brett Mason’s declared subject, but in fact Saving Lieutenant Kennedy bears out the old adage that you can’t judge a book by its cover. Mason’s account of the rescue and the New Georgia Campaign in which the PT-109 was engaged takes up less than forty pages. The other four-fifths of the book is an encomium of the Australian-US relationship, to which biographies of Evans and Kennedy have been rather awkwardly attached. And so, the reader wonders, if the intention was to produce a general history of US-Australian relations, why rope Evans and Kennedy into it? The PT-109 saga tells us little about the bilateral relationship; indeed, for years Kennedy believed Evans was a New Zealander. And the parallel biographies of Evans and Kennedy, including the story of Evans’s visit to the White House in 1961, really only serve to show how little the two men had in common.

Saving Lieutenant Kennedy has its interesting aspects. There is the account of how the PT-109 story became central to JFK’s political career, a process which began in August 1944 when his father, Joseph Kennedy Sr, used his influence to place an account of the episode in the mass circulation Reader’s Digest. Kennedy’s wartime heroism helped him to defeat Hubert Humphrey in the crucial 1960 West Virginia Democratic Primary, paving his way to the White House. Then there is the story of the Solomon Islanders who participated in the rescue, including that of Evans’s principal scout, Benjamin Kevu, who made his own visit to the White House in 1962. Kumana and Gasa had previously been invited to Washington, but they were prevented from leaving Solomon Islands by the colonial authorities. However, Kennedy’s family has not forgotten them: recently the US Ambassador to Australia, Caro-line Kennedy, visited the Solomon Islands, meeting the families of Kumana and Gasa, and swimming one of the open water passages between islands that her father swam repeatedly in his attempt to attract rescuers.

Much of the time, however, Mason’s narrative has little to do with his declared subject. There is a laudatory chapter about the 1942–43 campaigns in New Guinea, which has only faint relevance to the story of the PT-109. The book’s illustrations are a striking example of this focus on the periphery: among the sixteen pages of images, the one that really matters – a map of the area where the PT-109’s crew waited for rescue – requires a magnifying glass to read it.

And so the reader wonders further: if Mason wanted to tell the story of Saving Lieutenant Kennedy, why didn’t he make more of it? Rather than yet another paean to the Diggers in New Guinea, why not write about the New Georgia Campaign itself, and the Coastwatchers’ role in it? There’s more to tell: two months before the PT-109 was sunk, a Coastwatcher base on nearby Bougainville had been wiped out by the Japanese, emphasising the dangers that Evans and his colleagues faced. Eleven survivors were rescued from PT-109, but weeks earlier Coastwatchers on a nearby island had organised the rescue of ten times that number of survivors from the sunken cruiser USS Helena. In his 1945 classic Green Armour, the great Australian war correspondent Osmar White gave a vivid description of the New Georgia Campaign, concluding with an account of how he himself was severely wounded during a Japanese bombing raid on Rendova.

Full disclosure: the current reviewer was disappointed Saving Lieutenant Kennedy didn’t say more about the unique atmosphere of the small boat war in which JFK fought. During the Pacific War, in the same Solomon Sea waters where Kennedy was sunk, my father, Marsden Hordern, served on small wooden vessels operated by the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Reg Evans, after leaving the Coastwatchers, actually finished his war service in one of these RAN workhorses. In his memoir, A Merciful Journey (2005), my father writes about how, like the PT-109, these small boats rolled heavily in any kind of weather, how they leaked, how appallingly hot and humid they were below deck, how their engines posed a terrifying fire risk, and how they were so fragile that any enemy they met could sink them with one blow. He himself, by the narrowest of margins, avoided Kennedy’s fate of being run down at night by a large vessel – in this case an American military transport. And even now, at the age of 102, he retains a healthy respect for the destructive propensities of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Comments powered by CComment