- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Classics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wonders

- Article Subtitle: Julia Kindt’s thought-provoking new book

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The gods of the Greeks are uniquely anthropomorphic; they are not only imagined with human bodies but with thoughts and feelings largely similar to our own, except for the fact that they cannot grow old or die, and are thus spared the greatest part of human pain and suffering. They can feel anger at the misbehaviour, or pity for the fate, of mortals, as when Zeus sees that his beloved son Sarpedon is about to be slain (Iliad 16.431 ff.), but compared to us, they ‘live at ease’ (Odyssey 5.122 and elsewhere).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Christopher Allen reviews ‘The Trojan Horse and Other Stories: Ten ancient creatures that make us human’

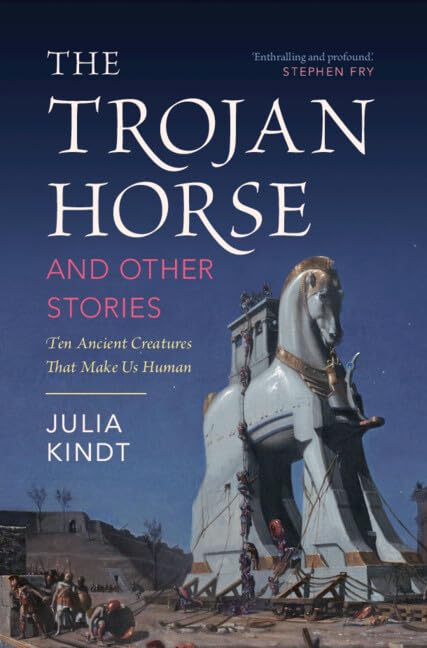

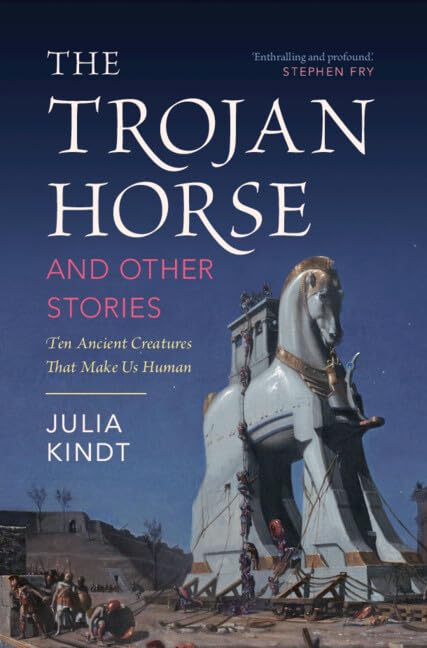

- Book 1 Title: The Trojan Horse and Other Stories

- Book 1 Subtitle: Ten ancient creatures that make us human

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press $47.95 hb, 370 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The theriomorphic divinities of the Egyptians, represented in the form of animals or at least with animal heads, were far more remote and incomprehensible; their connection to the subhuman world simultaneously recalled how alien their supra-human and spiritual reality was. In both aspects of their dual natures, these gods were categorically non-humanistic.

Animal forms could be temporarily adopted by the Greek gods, as when Zeus becomes a bull to carry off Europa to the island of Crete, but these are disguises, not the revelation of the divinity’s animal nature: Zeus does not turn into his emblematic eagle, for example. Permanent metamorphosis is another matter; in this case, humans at least do sometimes turn into creatures that reveal their innermost nature, as when Lycaon is transformed into a wolf.

The boundaries and distinctions between human and animal are themes that arise in all cultures, but they are no doubt particularly important in one whose sense of the human is so decisive that even its gods are conceived on this model. And this is precisely the subject of Julia Kindt’s fascinating new book about animals of different kinds in the ancient world – living, mechanical, fabulous, or metaphorical – and what they tell us about the relations between human and animal existence.

The creatures, the stories, and the ideas that Kindt evokes are so memorable that they have not only survived for two millennia or more into the modern imagination, but have in many cases become fundamental references, paradigms, proverbs, or even part of a language of ideas and forms whose origin has been forgotten. The Trojan Horse of the title, for example, is now used to describe a kind of digital virus by people who would in many cases be entirely ignorant of the Trojan War itself.

Kindt begins, in the book’s introduction, with the brief but significant episode of Odysseus’s encounter with his faithful dog Argos on his return to Ithaca (Odyssey 17.291 ff.); though disguised as a beggar, he is naturally recognised by the dog and recognises him in turn, wiping away a tear at the sight of the once-fine hunting hound he had himself bred as a puppy. This brief meeting, at the threshold of the palace he has not seen for twenty years, is a marker of the time that has passed as well as a reminder of a loyalty that contrasts with the treachery of humans like Melanthius and others.

The ten chapters that follow discuss, in much greater detail, the Sphinx, Xanthus, the speaking horse of Achilles, the Lion of Androclus (or Androcles), the Cyclops, the Trojan Horse, the Boar of Trimalchio’s feast, the Political Bee, the Socratic Gadfly, the Minotaur, and, finally, the Shearwaters of Diomedes. Each of these creatures has a rich and complex history in the myth and literature of antiquity, and an equally intriguing narrative and philosophical afterlife in the modern period.

To take one example, Achilles’ speaking horse is not just a wonder, but raises the fundamental question of speech as the faculty that most obviously distinguishes us from animals. As Kindt shows, the same theme is evoked in Kafka’s short story about an ape who becomes human by learning to speak. According to Diderot, the Cardinal de Polignac was so struck by the humanoid appearance of an orangutan in Paris in the mid-eighteenth century that he apostrophised it rhetorically: ‘Speak, and I will baptise you!’

The Cyclops in Book 9 of the Odyssey is not truly an animal, but, like the speaking horse, he makes us think about the boundaries between human and animal. He is not civilised, since he does not cultivate the soil or raise cereal crops; he is not political, for he is solitary, nor social, as he has no conception of hospitality and reciprocity. His cannibalism is especially problematic, since abstaining from eating one’s own kind is generally taken as a criterion of humanity as against bestiality.

Trimalchio’s boar, the centrepiece of his ludicrously ostentatious feast in The Satyricon, elicits reflections about hunting and meat-eating, and thus also arguments against eating the flesh of other living creatures. The bee has been an extraordinarily powerful political image from antiquity to the present day, while Socrates’ metaphorical gadfly leads us to ponder the role of individuals who question the orthodoxies of their day.

This is a truly thought-provoking book and a delight to read. It is addressed to the intelligent and educated reader, rather than to a handful of fellow specialists. The scholarship is extensive and thoroughly but discreetly referenced, so that it is easy to follow up any leads of particular interest. Although most of Kindt’s readers will no doubt have some familiarity with many or all of the subjects she deals with, she never takes this for granted.

Above all, she does not approach the past, as so often today, with an agenda or a set of judgements formed in advance of studying the material – in other words prejudices – but instead adopts a truly hermeneutic method, seeking first to understand what these stories and themes meant in their own time and, on that foundation, pursuing their subsequent history and their resonance for us today.

Comments powered by CComment