- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘When I am famous’

- Article Subtitle: A masterpiece of biographical synthesis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

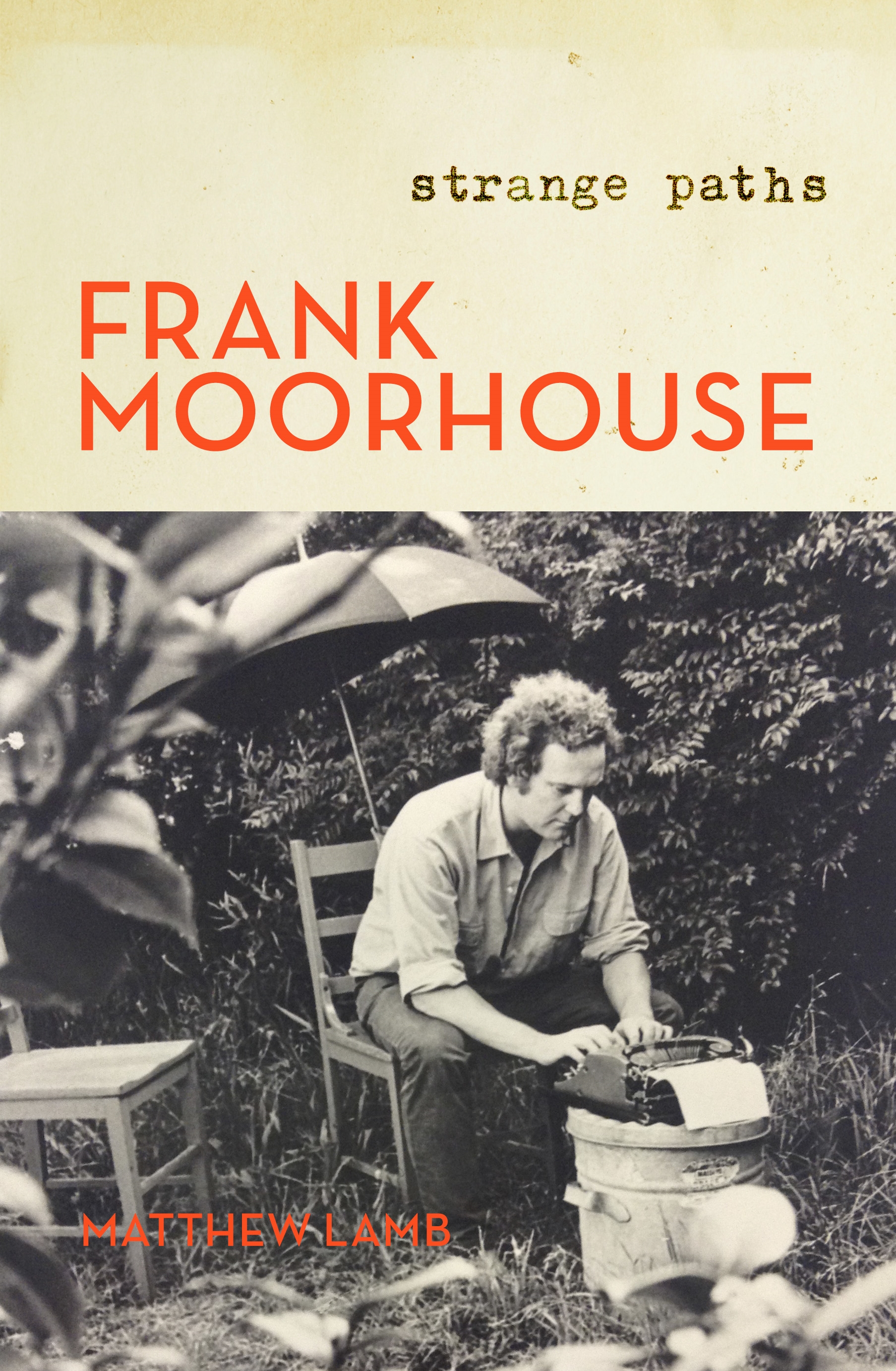

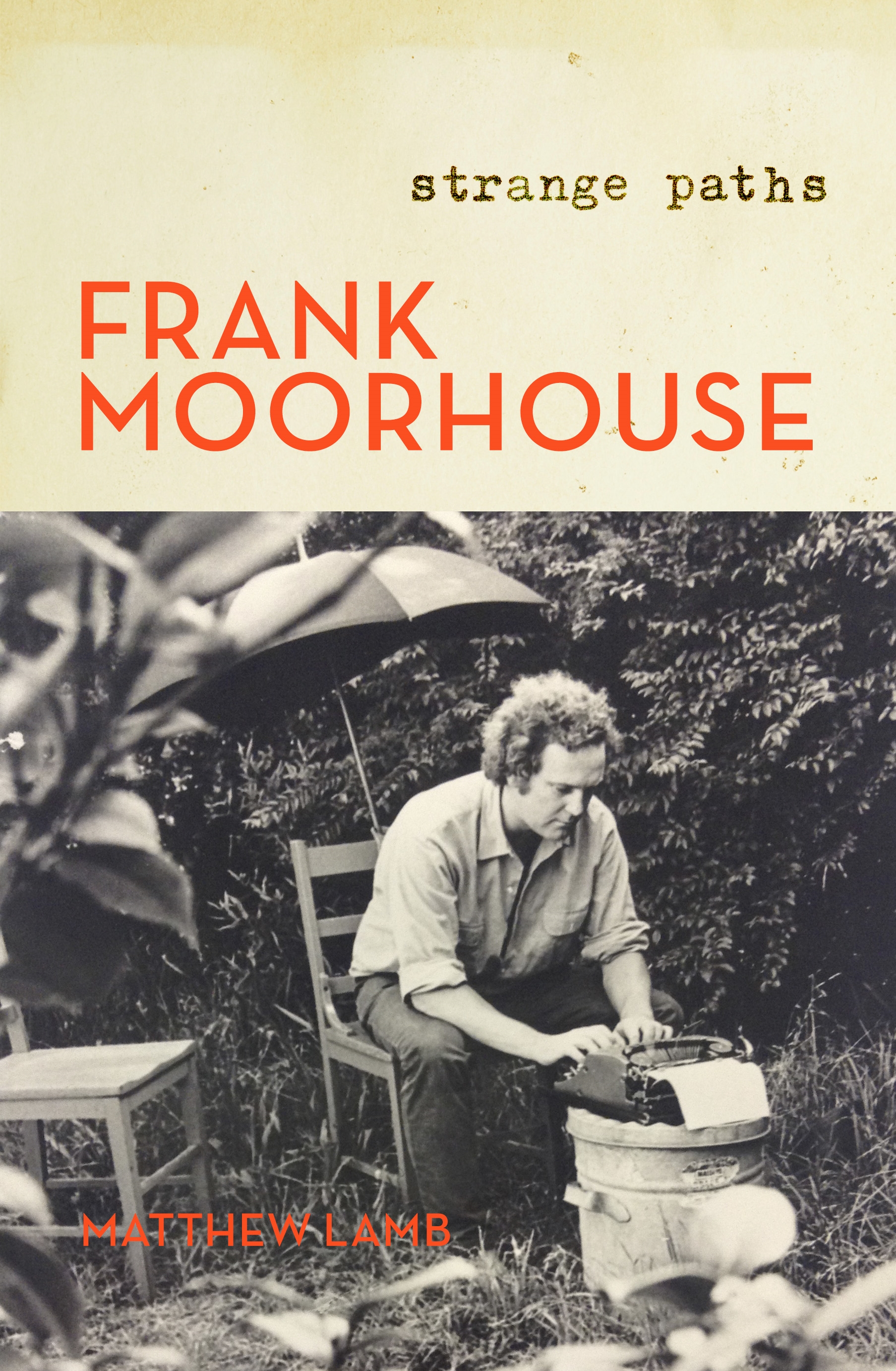

Frank Moorhouse: Strange paths has no introduction, but Matthew Lamb describes it in his author’s note as ‘the first in a projected two-volume cultural biography of Frank Moorhouse’, covering the long writing apprenticeship of 1938–74 during which Moorhouse ‘br[oke] into the literary establishment, on his own terms’. Lamb does not explain his use of the term ‘cultural biography’ within the book, but the term is apt to describe how ‘biography intersects with social history’ as the book tracks Moorhouse’s ‘negotiation of shifting social conventions and historical moments’ (as Lamb puts it in an article on the Penguin website titled ‘“When the facts conflict with the legend” – How does a biographer balance storytelling with the truth?’).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sascha Morrell reviews ‘Frank Moorhouse: Strange paths’ by Matthew Lamb

- Book 1 Title: Frank Moorhouse

- Book 1 Subtitle: Strange paths

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $45 hb, 480 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Frank Moorhouse is a masterpiece of synthesis. Lamb has amassed insights from a remarkable range of sources, from private correspondence and notebooks through to unpublished or uncollected fiction and essays. Fascinating juvenilia testify to Moorhouse’s extreme precocity as a satirist and social observer, and to the early onset of a lifelong habit of intensive self-scrutiny (which did not always translate into self-awareness). The archive is enlivened with oral history; gleanings from myriad conversations and interviews with not only Moorhouse but numerous intimate acquaintances of the author, including some anonymous and highly sensitive material.

Having ‘immersed himself in [Moorhouse’s] archived life’ and its cultural contexts, Lamb stays submerged throughout Frank Moorhouse, as the discreet yet abiding presence holding together the whole. Rarely does this biographer editorialise or draw inferences from the material, implicitly trusting in readers to make the connections. He seems to be writing neither for a broad audience nor for insiders, nor for himself, but as if driven by a sense of duty to do justice to his subject for an abstract posterity. His bare-minimum bio on the book’s dustjacket is an index of this self-effacing style: a mere four lines convey that Lamb is former editor of Review of Australian Fiction and Island magazines, and that he has two PhDs (in Literature and Philosophy). And I won’t lie: the book often reads as though it were written by someone whose passion for research could hardly be exhausted by one PhD alone.

Lamb is addicted to the archive. The book does not begin with any big-picture claims about Moorhouse’s cultural significance, or by making a case for his continued relevance. Instead, following an epigraph drawn from an ‘undated index card’, Lamb opens the first chapter, rather bravely, with reference to a handwritten emendation Moorhouse made to his typescript for a 1980s talk before the Nowra Historical Society. The second paragraph introduces ‘another set of typescript notes’ (no date given) from the Frank Moorhouse Papers at the University of Queensland. The handwritten emendation concerns the need for ‘the right words’ to accurately record one’s impressions. Moorhouse aficionados will perceive resonances with the preoccupations of more than one Moorhouse protagonist and with persistent themes in Moorhouse’s non-fiction. But Lamb provides no orientation for less seasoned readers. On the second page, without further ado, Lamb tells readers that to understand Moorhouse it is first necessary to ‘examine the archival ghosts that Moorhouse carried within himself’ and proceeds to what he calls an ‘impressionistic prehistory’ entwining ‘fragmented […] seemingly unrelated historical stories’.

Don’t get used to even this degree of signposting. Unless you already know a lot about Moorhouse, you won’t know why Lamb is introducing this or that theme or motif at a given point. For instance, if readers have enjoyed Moorhouse’s fiction but are unacquainted with Moorhouse’s twin obsessions with literary censorship and copyright, they may be puzzled as to why Lamb’s prehistory includes information on these matters as they evolved in Australia over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A subsection on Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of His Natural Life is one of several that make no reference at all to Moorhouse’s forebears, ending on the coy observation that ‘Clarke’s talent reached beyond the capacity of his own society to justly reward that talent’. Did Moorhouse admire Clarke? If you don’t already know, Lamb won’t update you. This whole chapter is full of winks and nudges (or, in contemporary parlance, ‘Easter eggs’) for the seasoned Moorhouse reader, of whom I fear there may be fewer these days than Lamb would like to imagine.

All this is another way of saying that Lamb does not tarry with the ‘so what?’ question. The book relies not only on assumed knowledge but also on assumed interest. This latter assumption is probably fair, in a literary biography, and some will welcome the snub to the genre’s storytelling conventions. In any case, the narrative gathers momentum as Lamb follows Moorhouse’s development through all the milestones we expect in a literary biography: how the author came to write his first story; his early experiences of publication and editing in school magazines; his discovery of authors who became literary influences; rejection letters, and so on (Moorhouse’s bloody-minded quest to be published in Meanjin, despite countless snubs, affords something of a comic subplot). There is his entry into journalism, compulsory military service, and evolving politics, including his famous association with the radical libertarian movement known as the Sydney Push (which Lamb presents as being more ambivalent than legend would have it). Meanwhile, there are countless love affairs (I lost count, anyway) including several on-again, off-again attachments. Perhaps the most important love affair of Moorhouse’s life was his relationship with alcohol, about which Moorhouse was already writing as early as 1955, a full half-century before Martini: A memoir was published.

In his article on the Penguin website, Lamb relates that he had never really considered how biographies were written before taking on this project, and had to abandon his initial ‘embarrassingly naïve’ plan of establishing a chronological outline then fleshing it out from the archive, for he found much that contradicted ‘the legend’ and his timeline. What Lamb did not abandon was the chronological approach itself, which is perhaps somewhat surprising, given Moorhouse’s championing of the discontinuous narrative as a literary form.

Frank Moorhouse is actually more strictly chronological than most literary biographies, which tend to point back and forward in time to foreshadow how later developments in an author’s life and career relate to earlier ones, creating suggestive juxtapositions through prolepsis. Not Lamb. Apart from the prehistory, the book’s Coda is Lamb’s only extended excursion in the deliberate arrangement of materials independent of chronology, hopping more freely between texts and time periods. It is here that we find out, in the most understated way, the source of the book’s subtitle, ‘Strange Paths’ – and we get Moorhouse reflecting on his prehistory in ways that sound very much like what Lamb attempts in early chapters: ‘piece together my customs traditions track back before parents’.

Moorhouse himself was no stranger to abandoning careful plans. In the book, we see Moorhouse aspiring to an intentional life, engaged in continual self-scrutiny of his approach to writing, personal relationships, and just about everything else. But Lamb reveals a person whose in-principle commitment to radical honesty was undercut by shame, secrecy, and self-deception, and whose obsession with order was offset by hedonism (besides the excessive drinking, Lamb mentions unpaid accounts from David Jones’s gourmet food court). Moorhouse’s lifelong fascination with etiquette and good form is evident in his earliest writings, such as his formal acceptance letter (written when he was eleven) thanking his father for ‘the opportunity of coming’ to the staff dinner of Frank Sr’s company. Characters in stories Moorhouse wrote at sixteen or seventeen cultivate personal codes of conduct, while Moorhouse’s notes for those stories include reflections on his purposes in writing them. The will to intentionality is nowhere more clearly documented than when Lamb quotes from two starts Moorhouse made on keeping a private journal:

Today I have decided to begin my journal. I am aged 17 and 5 months. I think the journal will record what I call ‘seeings’ which will provide material for future stories.

Today I have decided to write a journal. I am aged 18 years and 5 months. I think the journal will consist of what I call ‘significant incidents’ which will provide material for future literary work.

Such regulated, intentional exercise of the creative faculties is redolent of Moorhouse’s T. George McDowell and reminiscent of Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby, with his gauche boyhood notes for self-improvement. Far more revealing is that the gesture had to be repeated, showing a failure to stick to the plan.

It is rare for a literary biographer’s subject to provide such an extensive running commentary on his own Bildung as Lamb found in Moorhouse, whose teenaged writings include essays with titles like ‘The World and Me’ and ‘Rambling in the Mind of an Adolescent (Part II)’, extrapolating general observations about ‘adolescents’ from himself as case study. That Moorhouse was hardly what is now termed neurotypical is suggested through the author’s own words in the title of Lamb’s fourth chapter, ‘I Feel Like Some Other Species Looking at Humans’. But it is not until page 437 that Lamb mentions a review of The Electrical Experience (1974) calling T. George McDowell ‘a South Coast Martian’, so that readers might connect the fact and fiction. Lamb is too sensitive to the thorough transfiguration of lived experience through imaginative writing (on which he can quote Moorhouse himself) to produce naïve biographical readings of Moorhouse’s fiction.

Like his heroine Edith Campbell Berry, with her capitalised ‘Ways’, Moorhouse meditated extensively on social and sexual etiquette in both private and published writings. He was famously in favour of sexual freedom and frankness, in principle at least. Lamb, in turn, would never insult readers by suggesting they would be so closed-minded as not to want to hear the details of Moorhouse’s sexual experience, right down to the stickiness of his first wet dream. Yet there is something curiously decorous and contained in the way that both Moorhouse and Lamb write about sexual experiences, whether positive or negative, and Lamb’s respectfully straightforward treatment of such matters as erectile dysfunction, internalised homophobia, and sexual assault is admirable.

I was surprised by the very young age from which Moorhouse’s preoccupation with, and conduct of, sex and relationships were informed by book learning, from Dorsey and Kinsey to (later on) Sartre and Beauvoir, even Durkheim. There is also a whiff of the boardroom. In Chapter Seven, Lamb cites a typescript in which Moorhouse outlines a ‘four-stage plan’ for salvaging his relationship with then girlfriend Sandra Grimes. ‘Certain parts of the central relationship must be preserved and protected,’ Moorhouse informed Grimes, adding: ‘It is perhaps a case of symbols and rituals. Symbols and rituals which mark the faith and strength of the relationship.’ It’s as if Moorhouse is talking about a participant in a clinical study, rather than himself. One of his ‘discussion papers’ for Sandra parenthetically promises ‘an appendix on “Honesty” to come’. For me, the heart of the book came in this seventh chapter, where the deep contradictions of Moorhouse’s outlook on life and relationships are most exposed, yet also properly historicised, as an index of Moorhouse grappling with his sexuality and gender identity in a repressive culture he himself helped to change. Nonetheless, it is hard not to feel frustrated for Wendy Halloway, who was married to Moorhouse from 1959 to 1963, when Lamb describes Moorhouse ‘espousing to her what he called his “Frankness and Sincerity Theory’” only to commence a clandestine affair with John Burrows (one of many things he withheld from her).

Moorhouse was such an eclectic, complex, and contradictory person that Lamb’s book provides an intense, even gripping, reading experience by the sheer depth of access it affords. There is, moreover, far more art to Frank Moorhouse than might be assumed at first glance. Far from lamenting a lack of selectivity, one suspects that what we are given is a tiny fraction of what was available. Every page holds intrigue: I was unaware of the extent of Moorhouse’s acquaintance with Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, or the manner of Moorhouse’s falling out with Michael Wilding. If I longed for a little more editorialising, it was only because Lamb is so insightful. In the stray moments when he allows himself to gloss an incident or passage, his observations are pithy and perceptive, as when he comments on Moorhouse’s tendency to ‘hid[e] behind a rational framework, speaking in generalities’ as a covert confessional mode, or when he deftly summarises the complex tone of ‘Filming the Hatted Australian’ in The Electrical Experience.

Frank Moorhouse is not a story of material struggle. Moorhouse experienced scarcity and precarity at times, but this was usually because he relinquished steady employment to concentrate his energies on becoming a professional writer (the idea of the writer as worker was one of Moorhouse’s own research interests). Much of the melancholy I felt while reading this book was for the current generation of aspiring young writers and journalists for whom the paths Moorhouse was able to carve out may look not only strange but downright otherworldly. A school leaver who was never a top student immediately gaining employment as a copy boy then working his way up as a cadet journalist through to editing a regional newspaper (remember those?) by the age of twenty-one, without any professional qualifications? Today, what equivalent paths would be open to one with Moorhouse’s talent and energy? And let’s not get started on the funding landscape for Australian literary magazines (which Lamb himself fought valiantly to palliate during his editorship at Island).

It seems apt that this volume culminates in the publication of The Electrical Experience, itself a ‘cultural biography’ of sorts (and by far Moorhouse’s best work, in my view). I hope that Frank Moorhouse will bring renewed attention to Moorhouse’s short fiction and discontinuous narratives, which the Edith trilogy has somewhat eclipsed. I was struck by the following lines Moorhouse penned in 1957, lineated as if they were verse, as some of Moorhouse’s more emotional private writings seem to be:

here I sit at my old school desk

where I wrote many to-be-world-shattering short stories

which lie in the folders

marked

1954

1955

carefully preserved to exist

those who want

my old work

when I am famous.

Lamb is one of those, of course: the ideal future reader Moorhouse could only have dreamed of at the time. We read these lines with the dramatic irony of knowing of the literary fame and fortune yet to come, but also with knowledge of the falling off in Moorhouse’s literary prominence in recent years. I fear I am one of very few people born after 1980 to have much interest in Frank Moorhouse (I doubt that many of my undergraduates have even heard of him). At the very least, Frank Moorhouse will be of great interest to a small audience, some of whom, like me, will eagerly await the second volume, tantalised by the words of Moorhouse, quoted by Lamb, that ‘no one tells the truth / all at once … / you get at it bit by bit’.

Comments powered by CComment