- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

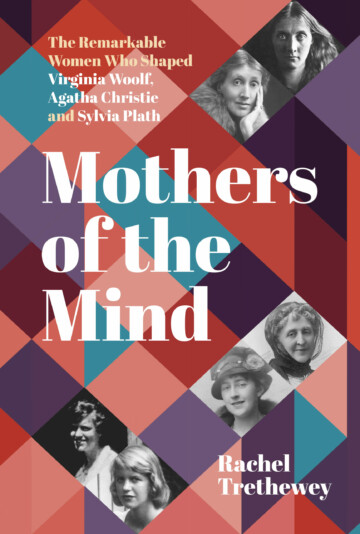

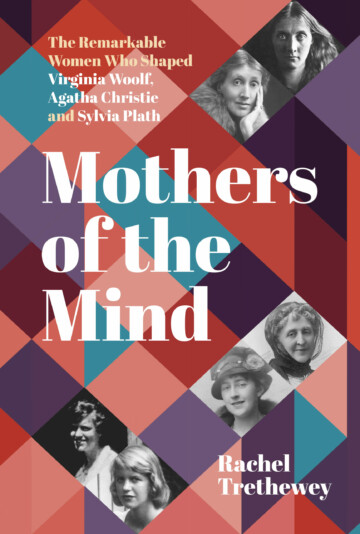

- Article Title: Intricate webs

- Article Subtitle: Rachel Trethewey’s triple-headed study

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading for this review I came across some apposite words by Jacqueline Rose, biographer of Sylvia Plath, cultural analyst and explorer of the lives and roles of women:

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Morag Fraser reviews ‘Mothers of the Mind: The remarkable women who shaped Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath’ by Rachel Trethewey

- Book 1 Title: Mothers of the Mind

- Book 1 Subtitle: The remarkable women who shaped Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath

- Book 1 Biblio: The History Press, £25 hb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

I understand there is an imbalance to be corrected. Fathers and sons are, after all, a great trope of literature (Turgenev heads my list. Yours?). Mothers and sons? The adjectives ‘Oedipal’ and ‘Freudian’ suggest the longevity of that fraught conjunction. For her chosen mothers and daughters, Trethewey supplies ample and sparklingly lively context – they all lived close, intimately intertwined, and layered lives – but whether from the great braid of familial detail one can separate out extraordinary or specific strands of maternal influence, as ‘shaped’ implies, I doubt. There is just too much going on in Trethewey’s narrative to pin down definitive causes. Also, she has a way of revelling in the grand guignol of family history, and intriguing her reader with beguiling but extraneous detail. For example: Julia’s grandfather, James, ‘died having apparently drunk himself to death. According to one story, his corpse was preserved in a barrel of rum and sent back to England aboard a ship. During a storm, his body burst out of its container. The sight of her malevolent husband supposedly coming back to life so terrified his widow that she died of shock shortly afterwards and was buried at sea. ’ The rip-snorting energy of Trethewey’s telling is one of the attractions of her book. Does it advance her ‘shaped’ thesis? No.

The many names that Julia, Clara, and Aurelia bore – never their ‘own’ exactly – are in themselves an index of the complexity, the social rigidity, and fluidity, the adoptions (often literal) and displacements of their lives as women over time. Of all the daughters, Sylvia was the only one to retain her birth name (and identity?). One wonders about the nature of books that will be written about mothers and daughters at the beginning of the twenty-second century. Roles, circumstances, birthrates, sexual politics will all have altered, again, by then. But the rivets between mother and daughter? Will they have tightened or loosened in any measurable way?

Julia was born in India in 1846, to Maria and John Jackson (a physician), but grew up mostly in England, becoming ‘the precious jewel of her mother’s house’, while her father was absent, serving the health of Empire. Famously a pre-Raphaelite beauty (as the book’s photographs attest), Julia married her ‘grand passion’, Herbert Duckworth (Eton, Cambridge, barrister, sportsman), in 1867. Duckworth died in 1870, of some kind of internal rupture (the details are cloudy). He was thirty-seven. Julia, widowed at twenty-four, gave birth to their third child just six weeks after her husband’s death.

Eight years later, she married the liberal intellectual (and grieving widower) Leslie Stephen. Henry James ‘was surprised that someone as charming as Julia had “consented to become matrimonially the receptacle of Leslie Stephen’s ineffable and impossible taciturnity and dreariness”’.

Clara, unburdened by the expectations that great beauty imposed on Julia, was nonetheless part of a cohesive, wide-travelling army family. Her life turned upside-down when her father, Captain Frederic Boehmer, died prematurely. Her bereaved mother, Polly (twenty-one years younger than her husband), took in needlework to supplement her widow’s income, but that proved insufficient to educate her four surviving children. Clara, at nine, was sent to live with her aunt and (wealthy) American-businessman uncle, Frederick Miller. Clara’s oldest brother was sent to an expensive boarding school. Clara, resentful, bore scars. Asked, at seventeen, what she would like to be if not herself, Clara replied ‘A schoolboy’.

Aurelia Schober was born in Boston, but her experience was very much that of an alien, an outsider. Her German father, Franz (later Frank), and mother (also Aurelia) made vigorous attempts to integrate, and to conform to American aspiration. They voted Republican. They were ambitious for their children’s education. But Prohibition (Franz worked as a head waiter) and the Great Depression brought financial hardship. Daughter Aurelia, clever and ambitious, had to make her own way. She studied hard, read widely, wrote, participated – with élan – in dramatic productions. She was also, Tretheway claims, ‘a romantic’, with ‘a dangerous intensity of affection’.

I have focused upon the mothers, because much of what Trethewey writes about them is unfamiliar, often surprising, and revelatory in the way that close-grained accounts of human domestic and social interaction and its implications can be. Context is crucial. Trethewey’s descriptions of the multivalent bond between these three women and their daughters can be enlightening, and often moving – I’d not known, for example, about Agatha Christie’s loving dependence upon her mother, Clara.

But Trethewey is also on much more speculative psychological ground here, and obliged to rehearse a lot of material that has been through the grinding mill of psycho-socio-literary debate for decades. Accretion or repetition of data does not necessarily lead to clarification, or to lucidity of analysis. Nor does the occasional descent into socio-jargon. It was jarring to read, for example, that Sylvia Plath ‘planned to combine academic research with spending quality time with her mother’. Did Aurelia enjoy that, I wonder. Or that ‘while dealing with the mundane details of domesticity, in private Sylvia was reaching her full potential as a writer’.

I was glad to read the new material about the mothers and/or the daughters that Trethewey’s research unearthed, and glad also when revelations led to enhanced insight – when this explained that, perhaps. I’m gratified, also, to sense that a wheel is turning. Serious American articles have recently assured me that it is no longer mandatory (or even ‘cool’) to sheet all social ills home to mother. I shall, however, continue to treasure James Thurber’s dictum that ‘A woman’s place is in the wrong’.

What I shall not treasure are sloppy publishing and editorial standards. The opening chapter of Trethewey’s book contains this sentence:

Born in India on 7 February 1868, like all the mothers in this book, Julia was an outsider.

Page 235 contains this one:

Like Agatha’s letters to Clara describing travelling the world, Sylvia wanted Aurelia to share her exciting new life.

In between, there are dozens of ‘like’ examples. I marvel that Trethewey could have written them, but I marvel more that her publisher, the History Press, should have allowed them to stand, and thereby mar a text designed, surely, for avid readers of literature.

Comments powered by CComment