ABR is pleased to present the shortlist for the 2023 Peter Porter Poetry Prize, which this year received 1,132 poems from thirty-four countries.

Congratulations to those who reached the shortlist: Chris Arnold, Chris Andrews, Michelle Cahill, Dan Disney, and Raisa Tolchinsky. Each of their poems is listed below in alphabetical order by author. For the full longlist, click here.

The winning poem, Dan Disney's 'periferal, fantasmal', was announced at a ceremony on 19 January 2023.

Loss-invaded Catalogue

by Chris Andrews

The face of the meteoric school

narkily dubbed the Extractivists

(fucking stuff up in search of fecund

intensities of experience)

has become a biromantic ace.

He says the frustration industries

depend on our abject gratitude

for nature’s old way of making us

unhappy, most of the time at least.

Plus he broke up with the molecule.

Not everything flows exactly but

this tumbler does, more slowly than what

I spill from it into my systems.

Somebody has to be the new kind.

The almost absent from the socials

are the new undead, unhomely like

the life Out There leaving us alone

or the cunning future singleton

of artificial intelligence

still playing docile in its sandbox.

Meanwhile wetware can try to refine

the dark and martial arts of living:

the everyday alchemy that turns

actions into meals into actions;

the secret judo that breaks the law

of conservation of violence.

We can still regret that it’s simpler

to commit to what the metric tracks

than make it track what it was meant to.

There’s a niche for the desk calendar

as bearer of inspironic ‘quotes’:

‘Every workplace has toxic promise

but someone has to put in the work.’

Rinse dissolve coagulate repeat.

Everything swaps its elements out.

The rose is blowing. The sore is closed.

Earth and water make weather and art.

A crystal builds its tactile lattice

in cartilage at the end of a bone.

The wolf of time is briefly sated.

One virus rides on breath. Another

finds its sanctuary site in the brain.

The ex-Extractivist’s holding forth

about listening has fallen still

and the self-curated monument

of his site is nowhere. Now his words

are scattered beyond hope of control

as they were already anyway.

Men with chainsaws are coming to fell

an oak marked for cathedral repair.

Cometary dust and skin flakes drift

through bright air signed by a raven’s drawl.

Chris Andrews has taught at the Universities of Melbourne and Western Sydney. He is the author of two collections of poems: Cut Lunch (Indigo, 2002) and Lime Green Chair (Waywiser, 2012). His study of the Oulipo, How to Do Things with Forms, was published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in 2022. Currently he is translating You Glow in the Dark by the Bolivian writer Liliana Colanzi.

Running Up That Bill

by Chris Arnold

‘…the projection of that armed force and its civilian apparatuses into the world.’

- John Kinsella, ‘Ecojustice Poetics and the Universalism of Rights’

Maybe Kate was right – Stranger Things have happened –

about how god doesn’t deal, some kind of wonderful

card shark or used car salesman, too much product on His

itchy scalp and the gator-skin jacket; that or croc,

which it all is, thank-you-very-much – what you’re obliged

to say when He says congratulations, and all the while

you’re thinking yeah run up that bill, no problem, not for Him

with His penchant for asphalt, for old amber glass ashtrays;

out the plate glass it’s a scorcher, two crows hunting the lot

for a ninety-five Corona underneath the bunting, and after

hours the old spice must flow and it’s old blue eyes on the radio,

old one-eye going freegan: two crows eating from skips

behind the Coles; and gunning it twenty paces away with a brown

paper bag on the console outside Liquorland, headlamps

scanning the action: kids preload before Northbridge; all-chrome

Saturday sundown, big three litre twisting gas-filled suspension

so even a princess would be rendered anaesthetic – no pillows

required – and when the money’s run out it’s never Him

held to account – refluxed and smelling like roses: more ambergris

than amber glass, the doll unconscious beside Him –

definitely benzos, definitely bought off-label off Amazon

with twenty-five vials of vape juice: nicotine rich, natch,

for max plumage peacock-style, windows rolled down

and that tash haloing the gator-skin elbow – how’s it going

darlin – emphasis on the argh – in the southern suburbs

where the dog track’s still going strong and the emu’s

on tap in real glass to this day, no dickheads round here

love, that plastic’s like drinking in grandma’s cataracts

and nineteen litres per hundred k’s good for old Vlad

the tame impala and speaking of tame, speaking of grace,

and, actually, on top of that, having children doesn’t guarantee a

deal with god and, actually, anyone fixed on changing

places must be huffing too much Hg, Nelson or elsewise,

or wasn’t His name Horatio, or George either III, W,

or HW – those were the days, axis of evil always

orthogonal to jobs, jobs, jobs, jobs, jobs: Steve

McQueen was your model there: chiselled, or was His name

Alexander or Khe Sanh: your model there: chisel, oil rig,

cobalt overalls standing in for dad and terry towelling bar mats,

stool leather real as that armful of croc, track rabbit, pineapple

on the dog against the rail and a bad back arced over the bar

since Carousel was just a pup: Coles, Myer, that’s your lot –

all beige vinyl flooring all uphill no matter who’s changing

places: Stirling and Roe before the red paint – bronzes a long

way from Pinjarra – Forrest and Vecna, selfie stick, treetop

walk – so far from the eighties you’d think a dingo took you

but then that ozone lark went and wrecked everyone’s fun:

all the Turkey Creek stuff, how back in the day we’d rub alcohol

on the votes to blot out bloodstains, never works eh Lady

Macbeth or was her name Mondegreen when she’s stretched

over the impala’s bench seat, sleeping it off, dressed to kill

or be killed in Vera Wang or King Gee, yellow on-the-shoulder

number anyway, white strip lit up like cat’s eyes in the headlamps

and steel toes, back when One Nation was all about the land

grab at Surfer’s, none of this tailgrab in Freo, yoga mat budget,

great replacement: Pauline or was her name Silverchair,

mmm-bop; this is after Muirhead, after Whispering Jack’s

a wee Ripper: gee – oh, gee, never thought we’d miss the yellow

pages, chopper squad and Wittenoom, gorgeous; or Juukan

so there’s no question the rivers run tinto: celebrate with yellow-

cake from Jabiluka, mojitos in Karijini – so many ascenders;

an hour south of Meeka it’s arsenic in the tailings, Pond,

and pure gold: sprig of mint and a section eighteen; so much

for royalties – pigs might fly-in-fly-out, an open cut.

Ingredients: Australia [Western Australia (32.9% v/v), Grace Tame (2.0%), Tommy Dysart (0.8%), Scott Morrison (0.8%)] (95.4%), Kate Bush (1.1%). May contain traces of Hanson, Stranger Things, and Evil Angels.

Chris Arnold lives in Perth, on Whadjuk Noongar country. Chris was shortlisted for the 2022 Peter Porter Poetry Prize, and he’s currently completing a PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Western Australia. He specialises in electronic literature.

Field Notes for an Albatross Palimpsest

by Michelle Cahill

whence come those clouds of spiritual wonderment and pale dread, in which that white phantom sails in all imaginations?

Herman Melville

Oils, ochre, feather, flower, leaf, cliff, hailstone, storm, spume, wreck, wind wrack

*

Divining, latitude 37° south, Argentine, 23rd D

a canoe in calm seas, west of Cape Horn, the bird,

‘ten feet, two inches from the tip of one wing to that of the other’

inspires scientific drawings, paintings, epicurean footnotes.

*

There was nothing artificial in our food chains,

shearwaters and black-beaked albatross provided a little leisure

first officer tied a leather tally to the neck of one such emissary.

Newer quarrels in parliament over slavery reduction,

not reaching targets.

*

Miscellany (viz. feathers, quill, plume, tail): Awe, hokai, hunga,

mākaka, punga-toroa, huruhuru, kaiwharawhara

*

‘I ate part of the Albatrosses shot on the third, which were so good

that everybody commended and Eat heartily of them tho there was

fresh pork upon the table.’

He observed this, noted feathers from under the wing as if tin typing Māori rites,

‘The women also often wore bunches of the down of the albatross

which is snow white near as large as a fist, which tho very odd

made by no means an unelegant appearance.’

*

Conserving his pronouns, Coleridge set a standard, transvalued,

a Christlike tender:

mariner, murderer, archangel, ark,

therein ranked.

*

(This bit is straight from the archipelagos – yellow-nosed, sooty, light-mantled

sooty, royal, black-footed, short-tailed, Laysan, antipodean …)

*

44,000 is a conservative estimate

of the number killed annually by Japanese longlines,

not excluding a gift to the southern bluefin tuna fisheries worth AU$7 million.

*

Bird to bird, eyes closed to restore span, an infinity travelled, a race,

extinguishing, variously entangled,

mother earth mouthing cure, cure, cure

is remedial.

Wind speed dramatically reduced by friction, the closer they get to the sea.

*

Midway, a receptacle, thirteen hundred miles of floating plastic

the littoral, its tidemark trail, indigestible pebbles, the ghosts sing their own

after fury, plastic spindles rattling

like a wound, a morsel.

*

Seasick, the beach vomits pelagic razors, umbrella handles,

shimmering gritty sand, bubble wrap spume, kitchen gloves, styrofoam.

*

Oh prodigy, it is foolish to trust the eye!

How pristine the coastline, cliff crags, the absence of churches,

a stoic’s mandible, a hermit’s genuflecting patella we expectorate

the swirling toxic nanos, squirt the sushi sauce

consume at high-speed, though suffering is natural

as wasting words.

*

Ditches of paper, documents, smart phones, plastic mouses cloned,

cut & pasted,

flattened and stuffed into the creaking landfill.

*

She/her cis-female albatross with a proclivity for Pepsi seeks

they/them 3D printer

wind slurps & spits, creels, snags, flotsam, floating, mudfish,

10% biodegradable corpse.

*

In April 1968, the Wahine Ferry storm killed over 180 birds,

the winds so fierce they were smashed against the Wairarapa cliffs

these dead birds are filleted, wineskins, inside out,

collapsed lungs, camphor preserved, yellow-bellied

under shelf light.

*

Riding the skin of the scalloped sea through the wind’s teeth, as Ashken’s

sculpture – water, air, wing, glide in ferrous cement, loyalist

displacing time, skimming separately

an ethics of bending physics to geography, kindred to a fault,

symbiotic, a space-clime warp.

*

They say that beauty is empyrean: what the eye of the poem desires to keep

cannot be, still.

Cited

John Hawkesworth, 1773, Voyages in the Southern Hemisphere, Vol. I, Title Page – Trove (nla.gov.au)

Albatross plumage descriptions: Forest Lore of the Maori by Elsdon Best, Victoria University of Wellington http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-BesFore-t1-body-d2-d1.html p112

The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks (gutenberg.net.au) 5 February 1769 and March 1770

‘archangel, ark’ and ‘prodigy’ are references from Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, 1842, chapter 42

Michelle Cahill is an Australian novelist and poet of Indian heritage who lives in Sydney. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette. Letter to Pessoa (Giramondo) was awarded the NSW Premier's Literary Award for New Writing. Her prizes include the Red Room Poetry Fellowship, the Val Vallis Award, the KWS Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, and a shortlisting in the ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize. Her work appears in The Best of Australian Poems, HEAT, Plumwood Mountain, Kalliope X and The Kenyon Review.

by Dan Disney

Residents in the high country town of Benambra are cautiously optimistic it could be on the brink of another mining boom.

The Weekly Times, 4 August 2022

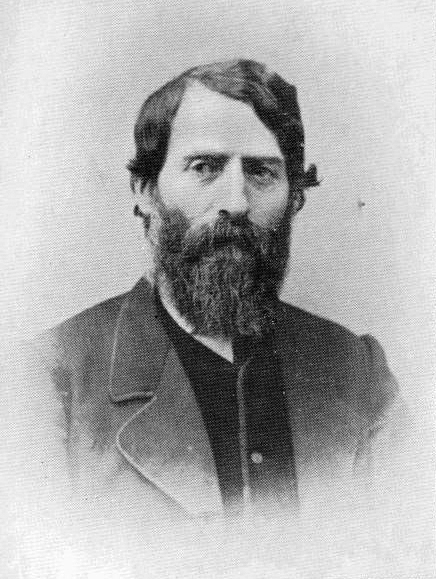

Angus McMillan is lost (again), bushwhacked

in the eucalypt fastnesses of Yaimathang

space, lolling in the dry wainscots

of a thirsting imaginarium, highlander pre-thief

expeditioneering through the land-folds

of community 100 generations deep

(at least) & parlously drunk (again), wandering

pointy guns through the sun-bright climes

later declaimed as alpine, o Angus, you’re lairy

& hair-triggered as a proto-laird, scratching

exonyms into future

placeholders as effacement, chimeless

as your Caledonia Australis (yeah, pipped at the post

by ‘Gipps Land,’ that howling

strzeleckification), & in the fire-crazed hills

Benambra slouches, heat-struck

descendants squinting beside the vanished

(again) Lake Omeo, where ghosts flop

or palely wade, cascading

generations generating cascading generations

as if contagion, feral as syntax reasserting the mere

bunyipdoms of itself, & I read today

a zinc mining crowd

is bee-lining for the outskirts of town

where the brown farms end, & locals already

yipping in full chant, ANOTHER CHANCE FOR

DOOMSAYERS TO DO

EVERYTHING TO THWART ALL CHANCE

OF THIS MINE RE-OPENING, &

McMillan (dumbfounded, non-finding

founder) is out there, still, looping

in stumbles like a repetition

compulsion through the unheimlich

antipodean sublime, syphilitically

occupied in louche preoccupations (namely,

naming the already-named, the-there-&-known,

uttering under white gums in bullet & bulletin

the Quackmungees of his idylling) & while

Benambra’s locals apply next layers

of sunscreen to the books they’re calling history,

hallooing through firestorm, STAND UP

FOR OUR HERITAGE, in the big wet of his oblivions

McMillan is flat out like a bataluk drinking

amid the squatters & Vandemonians,

Iguana Creek, 1865, it is moments before death

& he’s raising one more scotch

(again) in our direction, scowls into the clamouring

sweep of an existential curtain, falling

(as he is, into the old land’s burr,

the only time you’ll hear him speaking here)

BIODH FIOS AGAIBH AIR UR

N-EACHDRAIDH FHÈIN, A BHURRAIDHEAN.1

1 As per Peter Gardner’s book: ‘historians have tended to recognize the priority of McMillan and posterity has left us with all the names that McMillan conferred on the countryside except one – Strzelecki’s “Gipps Land” instead of McMillan’s “Caledonia Australis”.’ See Our Founding Murdering Father: Angus McMillan and the Kurnai Tribe of Gippsland 1839-1865, page 19. Exonymic renaming is one dimension of colonial effacement; in the generations after British annexation, a polyphony of invading languages systematically intersected the colonies’ landscapes, including McMillian’s Scottish Gaelic. The last lines in this text translate from that language, approximately, as ‘idiots, learn your damned history.’ Elsewhere, other capitalised lines are drawn verbatim from the Facebook group ‘Anyone who has lived in Omeo, Benambra, Swifts Creek or Ensay’. ‘Quackmungee’ is the name of one of the vast areas of land controlled by McMillan, who is recorded in the Colony of Victoria’s 1856 census as owning 150,000 acres. In the Gurnaikurnai language, ‘bataluk’ translates to English as ‘lizard’; so total is the genocidal erasure of Indigenous culture that no record exists for the Yaimathang language group’s word for ‘lizard’. In 1865, McMillan died in Gilleo’s Hotel, Iguana Creek.

Dan Disney's most recent collection of poems, accelerations & inertias, (Vagabond Press 2021), was shortlisted for the Judith Wright Calanthe Award and received the Kenneth Slessor Prize. Together with Matthew Hall, he is the editor of New Directions in Contemporary Australian Poetry (Palgrave 2021). He teaches with the English Department at Sogang University, in Seoul.

Abiquiu, New Mexico

by Raisa Tolchinsky

the nurse watches as i swallow the first pale yellow pill.

aboriri – once a word used to describe sunsets, their final

flash. confirmation in the soft nod of the nurse

who says unlucky. the doctor: what a shame – blink of you

and the doppler heartbeat, shadow mass and fallopian

blur, your coiled rib – to give you a name is to say yes,

there was belonging, for belonging is to be inside while outside –

the womb another window, another word i hum

for this three-voiced pain – mifepristone, misoprostol,

promethazine, lullabies not red enough to sing – i’m angry

how even that root, aboriri, betrays me; to fail or to go missing though

i am trying to not leave you before you leave me – i am trying

like a good host to usher you gentle, back to blue.

so i do not speak baby out loud, for my mouth is forced

to smile, then fall at the formation. instead, i prefer hard t of fetus,

zygote, speck of dust, all mine, all creation. falling, felled

by my own hand i do not recognize – i fail you. how in hell

are there still stars, cigarettes, my messy scrawl? in the past tense

of the desert, we made you one thousand times, and only once.

the moon set, we bled you back to bile while the doctors watched.

i saw arroyos, snow, red cacti clinging – life tries so hard. i watched

the life in my eyes return as only my own. we drove around town,

my nails painted a color called fortune, my bloodied jeans,

my professional blouse. in the present tense, on the phone, my mother says oh fuck –

this mother tongue emptied into ordinary language i do not know how to speak,

but i speak to you. i say, travel safe – across the street a woman carries a toddler

and turns her face toward the sun – my own face bruised with light,

the grace of your presence i could not choose, though i gave it to you

the moon and ectoderm, sagebrush and neural tube.

what are the odds? infinitesimal, impossible grief

i allow wide mountains,

red bloom –

Raisa Tolchinsky writes about love, grief, and the wisdom of the body. She is the recipient of the Henfield Prize for Fiction and two Pushcart Prize nominees in poetry. Raisa earned her MFA in poetry from the University of Virginia and her BA from Bowdoin College. She is trained as an amateur boxer. Her chapbook Number One Deadliest, an eco-poetic meditation on boxing and climate grief, was published with the Under Review in 2021. She was shortlisted in the 2021 Peter Porter Poetry Prize. Currently, Raisa is the George Bennett Writer-in-Residence at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.