- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ambiguous gifts

- Article Subtitle: Two young men from Adelaide

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

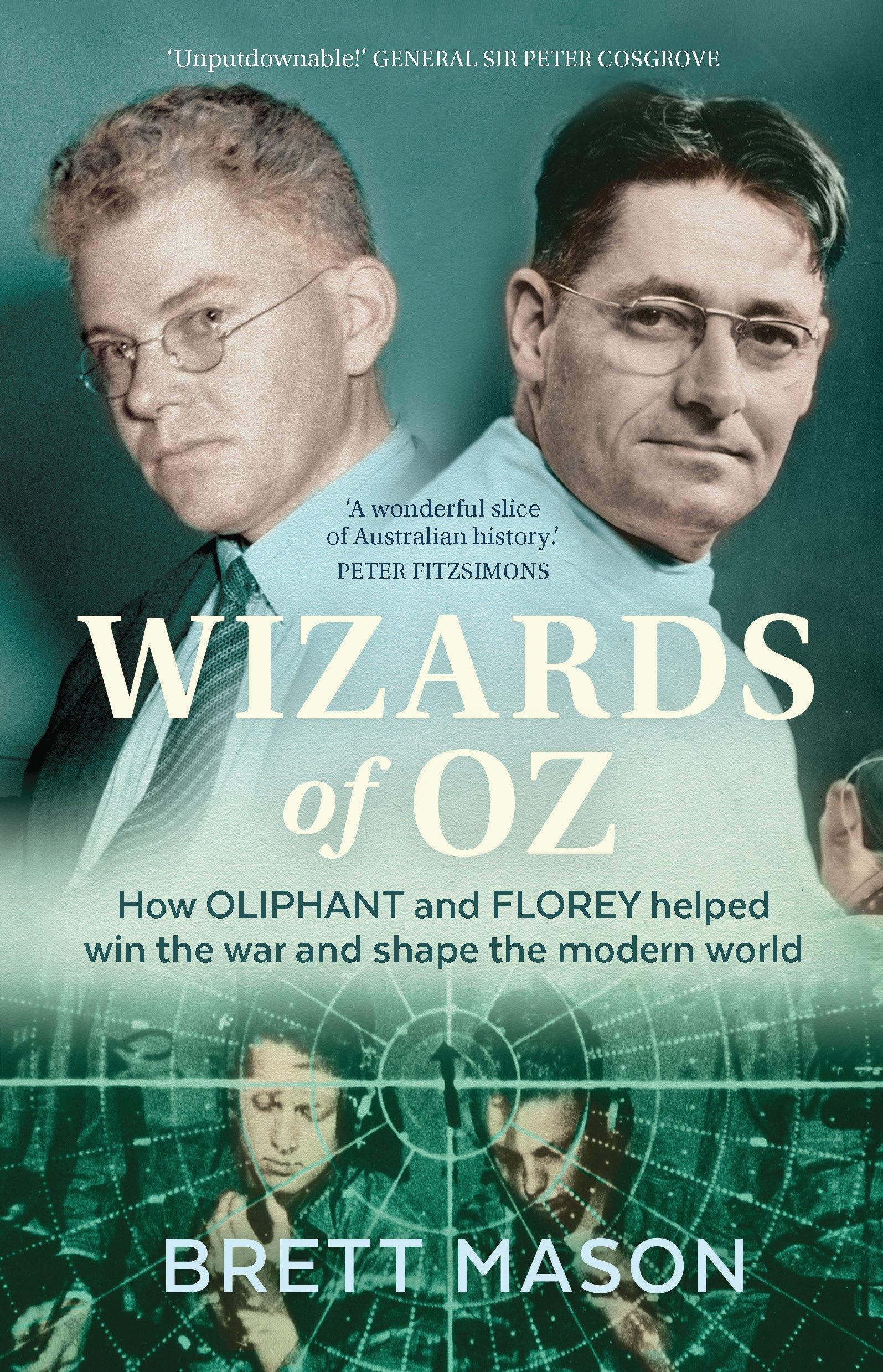

What happens when you mix some of the biggest scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century with the urgency of war? Wizards of Oz, a new book by lawyer and former politician Brett Mason, seeks to provide the answer. It is an account of a friendship between two Adelaide men and their extraordinary scientific achievements during World War II.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Julia Horne reviews 'Wizards of Oz: How Oliphant and Florey helped win the war and shape the modern world' by Brett Mason

- Book 1 Title: Wizards of Oz

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Oliphant and Florey helped win the war and shape the modern world

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 424 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

While the language is too flowery and sentimental – at least, for this reviewer – the idea of scientific endeavour, knowledge, and expertise as wartime instruments of defence and attack is one of the major hallmarks of modern warfare. It was first seen on a grand scale during World War I, when governments on both sides began to fund scientific and technological research in the hope of victory.

But not only governments. Doctors – including women doctors who served in privately funded war medical corps – often received modest grants to conduct scientific investigations in the thick of battle. Typhus was a common cause of death among soldiers. Gas gangrene was another. During World War I, small makeshift laboratories started to pop up in battlefield hospitals to investigate how to combat serious infections. For example, Dr Elsie Dalyell’s lab in Serbia, on the Eastern Front – where Dalyell and others sought to develop a vaccine against epidemic typhus – was funded by the British-sponsored Serbian Relief Fund. While typhus vaccines only became available after the war, we have here a window on how expertise and knowledge was brought into the folds of war to advance medical knowledge to save lives. These doctors worked on an important and often overlooked first defence against bacterial infections that in past wars had claimed more lives than weapons. In fact, largely because of this medical work, World War I (rather than World War II, as Mason claims) was to become the first war to reverse this deadly trend.

During war, science conspicuously became associated with a nation’s war aims. As Tamson Pietsch argues in Empire of Scholars: Universities, networks and the British academic world 1850–1939 (2013), the myth that science was somehow apolitical and ‘knew no nationalities, no enmities’ was debunked almost from the outset of World War I.

Given this earlier experience, from the very start of World War II scientific endeavour, knowledge, and expertise formed a crucial part of the British war effort. Enter Brett Mason’s depiction of how Florey and Oliphant were not only crucial to wartime research, but to the Allied victory. In some ways, his is a ‘boy’s own’ account with Florey and Oliphant the heroes. While there are gestures to contributions from their teams – for example, Mason writes of the Dunn School’s ‘Penicillin Girls’: ‘Without them, Florey and his team could never have produced enough penicillin for human trials’ – the overwhelming narrative is that Florey and Oliphant were the Great Men of the Allies’ scientific success.

The Great Men approach, however, has its limitations. As Mason explains, funding for these projects significantly increased as a consequence of war. We know that in the development of Covid vaccinations more money equalled more scientists to undertake the sort of painstaking process required in scientific research. In Florey’s case, it enabled a breakthrough, but only due to the team of men and women who conducted numerous experiments and trials. It was a similar story with Oliphant’s microwave radar. For me, this account misses interesting questions such as what scientific leadership meant during war, and how it was sustained by the work of ‘armies’ of men and women scientists. We get a glimpse of this wider workforce, but more as background noise rather than as crucial fodder for the argument.

Every great man is allowed an imperfection. For Florey, it was his loveless marriage to Ethel Reed, which he endured until she died in 1966. Fifteen months later, he married Margaret Jennings. Both were scientists who worked on Florey’s penicillin project, Margaret on the clinical application of penicillin, and Ethel on the all-important human trials. Yet their work is barely mentioned. How many other women, I wonder, were involved in the penicillin project, and what did this mean for Florey’s scientific leadership and for its success as a whole?

Oliphant, however, was happily married to Rosa Wilbraham. His weakness – the point where we start to doubt a man’s greatness – was the splitting of the atom in the early 1930s that led to the making of the atomic bomb (though Oliphant himself was not responsible for the latter). Mason delves into this moral dilemma for much of the latter part of the book, although he only touches the surface. He concludes: ‘Unleashing the power of the atom was a far more ambiguous gift to humanity than releasing the healing power of penicillin, and hardly redeemed by the benefits of an all-seeing radar.’

Even granting the moral ambiguities, that seems a cruel judgement to make of Oliphant’s life. Some readers will be perfectly content with the Great Men of History genre and will find this book reveals a new dimension of World War II. There is much to enjoy, not the least Mason’s accessible account of why breakthroughs in penicillin and microwave were so integral to World War II. But in the end, this history skims across the surface and never fully addresses Mason’s goal, that ‘Australia might learn as much from their spirit as from their achievements’.

Comments powered by CComment