- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Walking dollar signs'

- Article Subtitle: A national history full of puzzles

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

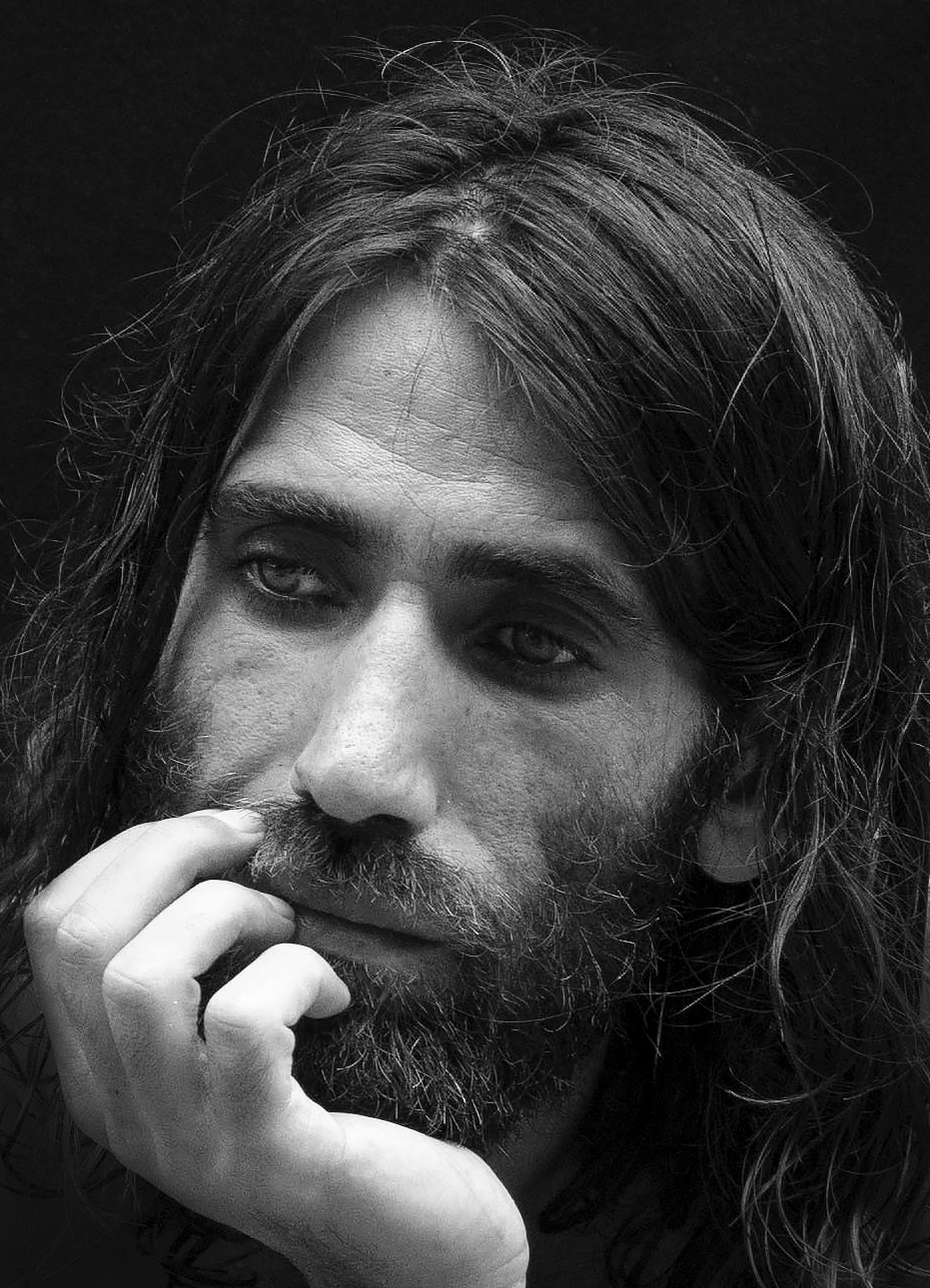

In 2018, No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison became a literary sensation. It was written by Behrouz Boochani, a Kurdish-Iranian journalist and refugee who was incarcerated by the Australian government on Manus Island. Like thousands of others, Boochani had travelled by boat to seek asylum in Australia. From Manus, he texted passages to collaborators in Sydney. There, Omid Tofighian and Moones Mansoubi developed the work further. Through reportage, storytelling and poetry, it bore witness to the horrors of immigration detention. By 2019, No Friend had won some of Australia’s major literary awards and Boochani had become internationally renowned. In November 2019, he was invited to attend a festival in Christchurch, New Zealand. After six years in detention, he was free. The system that had imprisoned him remained intact.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Behrouz Boochani, 2018 (Hoda Afshar/Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Hessom Razavi reviews 'Freedom, Only Freedom: The prison writings of Behrouz Boochani', translated and edited by Omid Tofighian and Moones Mansoubi

- Book 1 Title: Freedom, Only Freedom

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury Academic, $32.99 pb, 333 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Essays range in style from narrative to scholarly and poetic. Throughout, there is an abiding interest in the power of language to upend structures of violence. We begin on Christmas Island, after Boochani’s perilous boat journey from Indonesia. He and others are bundled aboard a plane by Australian officers. ‘I was confident that they enjoyed destroying our human dignity,’ he writes. He is deported to Manus Island, where he testifies to the wretched conditions there. Refugees are assaulted, starved, subjected to water deprivation, and placed in solitary confinement. Following the official closure of the detention centre in 2017, they are placed under siege and attacked for twenty-three days by local PNG authorities. Shaminda Kanapathi recounts the ingenuity needed to deliver food and water to 450 stranded men. Boochani adds dispatches that culminate in A Letter from Manus Island. Poetic and expansive, this manifesto sparked worldwide interest in Manus. Even as detainees were bashed, some placed red flowers in their hair. ‘Our resistance is the spirit that haunts Australia … humans have no sanctuary except within other human beings,’ wrote Boochani.

As in No Friend, the central concern in Freedom, Only Freedom is the suffering inflicted on refugees by punitive detention. Boochani provides examples through anecdotes and first-hand accounts. We learn of guards beating Iraqi and Iranian detainees. There is solitary confinement, where a grieving Pakistani man is left unsupported after losing his family. The Guardian’s Ben Doherty notices Boochani becoming emaciated; ‘every one of his ribs was apparent, as he huddled over to escape the wind’. We hear of the anguish of the vulnerable, including gay and transgender people, and those with mental illnesses. The indefinite nature of detention harms detainees in ways that are medically verifiable. (I have previously summarised this research in articles for ABR.) Sajad Kabgani sees refugees being rendered ‘timeless, uprooted’. Victoria Canning invokes the theory of necropolitics, where social – and sometimes physical – death is conferred on refugees. Australia, she writes, has committed ‘life theft’. The punishment is reinforced through language, in what Anne McNevin calls ‘epistemic violence’. She cites an example where Boochani climbs a tree in political protest. The authorities use bureaucratese to insinuate that he is mentally ill. Boochani retorts in literary language, insisting on his personal dignity and the right to be ‘above the fences’.

The simplest indictments are also the most powerful. Each part of the book names the people who have died in detention. This includes the suicides of Hamed Shamshiripour (‘Someone killed Hamed today’) and Salim Kyawning, and the deaths of Faysal Ishak and Hamid Khazaei. In 2014, Boochani’s friend Reza Barati was murdered by prison guards. In stirring poetry, Boochani grieves for Barati’s mother, who has become another victim of this ‘incalculable cruelty’. By July 2015, the Human Rights Law Centre and Human Rights Watch confirm that more people have died in detention than have been resettled by it. Boochani views this as systematised torture, meant to broadcast ‘what will happen to you if you try to come to Australia for refuge’. While legally difficult to prove, his claim is not made in isolation. Juan Méndez, a UN special rapporteur, finds that Australia’s treatment of people seeking asylum violates the UN’s Convention Against Torture.

Elahe Zivardar and Mehran Ghadiri believe that detention interlinks with an overarching ‘border-industrial complex’. Here, Australia’s security, military, and prison systems employ private contractors to create profitable black sites. Australian taxpayers funnel billions of dollars to client-states, oligarchs, and transnational companies who use detention centres as ‘an ATM’. Refugees are commodified as ‘walking dollar signs’. Boochani cites the Paladin affair, where $423 million in contracts are awarded to a security firm through closed tender. Anne Surma identifies systems that ‘speak of security and protection … which actually translate as violence against vulnerable human beings’. By locating sites offshore, Australia attempts to outsource legal liability and wash its hands. These are the economics of ‘dark development’, writes Mahnaz Alimardanian.

Boochani’s arguments are occasionally unresolved or seem contradictory. Reporting on detention has accidentally and freely advertised it, he feels; ‘all journalists, human rights defenders and politicians … have unintentionally been in line with this policy’. One wonders whether he includes himself in this analysis. He considers journalism ‘weak and superficial’, preferencing expression through film, theatre, and literature. Arianna Grasso reconciles this dichotomy by identifying the synergies that exist between journalism and the arts. Blanket criticism is reserved for International Health and Medical Services (IHMS), the healthcare contractor on Manus and Nauru. As a doctor who has worked on both islands, I have documented IHMS’s flawed role (‘The Detention Centre Diaries’, The Lifted Brow, 2018). However, some IHMS staff have become refugee advocates. Members of the medical community, for instance, were instrumental in getting detained children off Nauru.

In this ‘dark cave with no end’, there are reprieves. Read closely, Boochani has an eye for absurdity and a nose for dark humour. Speaking about No Friend, he told me: ‘Yes, it is a funny book! And the humour is a form of resistance.’ In Freedom, Only Freedom, he addresses his ID number, MEG45. ‘I tried to attribute a new meaning to the nonsense number … For instance, Mr Meg.’ Charm is found in an essay titled ‘The Man Who Loves Ducks’. Mansour Shoushtari, a refugee, cares for the crabs, dogs, and birds on Manus. And why? ‘One does not need to give reasons for love,’ says Mansour. In a poem called ‘Untitled’, a prisoner’s awe at observing nature is portrayed. Neither flippant nor farcical, these expressions affirm the identity of refugees within systems that would anonymise them.

Freedom, Only Freedom fulfils its duty to history admirably. ‘History will remember … this period as an embarrassing phase … that will plague generations to come,’ says Boochani. A scholarly work, the text is perhaps best categorised by Tofighian as being ‘anti-genre’. Towards the end, we learn of Boochani’s new life in New Zealand. He is free but conflicted, aware of the ‘human beings on a precipice’ left in detention. In an acme of irony, as I write this article he is visiting Australia to promote his new book.

In this landscape, some things are shifting. The Albanese government has released some refugees and resettled others in New Zealand. These small gestures occur synchronously with turmoil in states like Ukraine, Afghanistan, and Iran. The global refugee crisis is only worsening; one wonders how Australia views its duty to respond. As Boochani concludes, ‘The modern history of Australia is full of puzzles … what does humanity mean in Australia?’

Comments powered by CComment