- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Greed and crankery

- Article Subtitle: The many heirs of Ayn Rand

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There was a moment there, in the opening chapter of How to Rule Your Own Country: The weird and wonderful world of micronations, when I thought I was about to undertake an improving academic tour. The authors, Harry Hobbs and George Williams, are after all both legal academics. That first chapter has sections with earnest headings such as ‘What is a micronation?’ and ‘Why do people set up micronations?’. There are seemingly well-chosen quotations from experts, and a careful weighing up of definitions and opinions.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Frank Bongiorno reviews 'How to Rule Your Own Country: The weird and wonderful world of micronations' by Harry Hobbs and George Williams

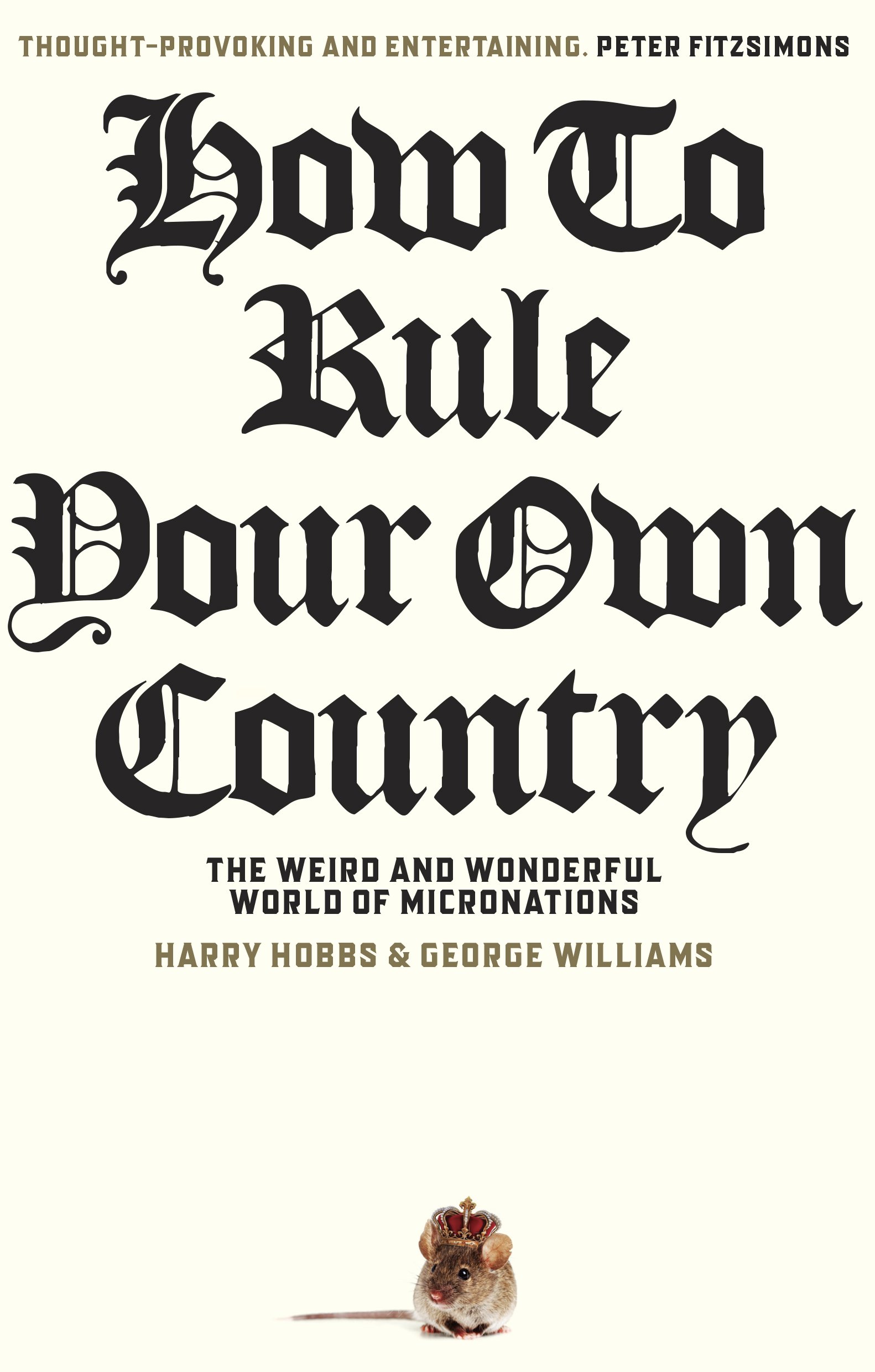

- Book 1 Title: How to Rule Your Own Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: The weird and wonderful world of micronations

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 308 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The best-known Australian micronation, and indeed one of the most famous examples in the world, is the Principality of Hutt River in Western Australia. It has its own chapter here, which tells the story of Leonard Casley’s establishment of the micronation in 1970 in protest against government wheat quotas that severely restricted his permitted output. The Australian political class and its bureaucratic arm were sometimes rather clumsy in their handling of Casley’s claims, furnishing him with replies to correspondence – indeed, sometimes addressing him as a ‘prince’ – that he then brandished as evidence of the micronation’s legitimacy.

Before long, Prince Leonard and his family – which included his wife, Princess Shirley – didn’t need to worry about wheat quotas given the tourist interest in his little province. Prince Leonard was also a favourite among journalists looking for a colourful subject for a feature article, and Hutt River attracted international attention. Eventually, with the Australian Taxation Office breathing down his neck over a massive income tax bill, Prince Leonard ‘abdicated’ in 2017, before his death a couple of years later. Covid-19 saw tourism dry up. His son sold the farm, the principality becoming one of the pandemic’s lesser-known casualties.

Despite the family problems with the tax office, Hutt River looks like one of the more benign micronations. The Principality of Sealand, established by the Englishman Roy Bates on an abandoned World War II naval fort in the North Sea that looks like an oil rig, had its origins in the battles of pirate radio operators with the BBC, the government, and other operators, the latter sometimes involving gun violence. There were rumours at one stage that Julian Assange might move his WikiLeaks server there. Like so many of these micronations, Sealand became associated with plans for a tax haven, and there was a trade in fake passports – in this case, issued by a Sealand Rebel Government in exile in Belgium.

American libertarians have recognised the potential of micronations. One Michael Oliver tried to establish a Republic of Minerva on a Pacific reef that at high tide was under half a metre of water. Ayn Rand has much to answer for as an inspiration for this kind of effort. Libertarian utopias involved the familiar plans for a tax haven, along with the provision of flags of convenience for shipping, hotels, casinos, fake university degrees, and facilities for secret banking.

Some were just outright scams, intended to relieve the suggestible of their money. One of these – the Dominion of Melchizedek – involved an Australian previously convicted in relation to the notorious Fine Cotton horseracing fraud of 1984. While that connection might amuse, there was nothing funny about the clever adventurer and conman Gregor MacGregor, an active fraudster in the early nineteenth century. He dumped 250 colonists in a mosquito-infested jungle in central America, supposedly the ‘nation’ of Poyais, where two-thirds of them died.

The point of most of this detail is the story itself. The authors write of micronations being ‘founded as creative attempts to build something new’, but many of the people they discuss were merely crackpots or crooks. Some efforts did begin, and even continue, as legitimate political protest against real governments that attracted valuable media publicity. There were also instances of creative political expression, and clever critiques of state sovereignty. But there is equally abundant evidence of extremism, greed, and crankery, alongside the ‘weird’ and ‘wonderful’ of this book’s title.

Comments powered by CComment