- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tinker Tailor Soldier Scribe

- Article Subtitle: The writer within

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Was he John or was he David? That’s the trouble with being a literary double agent: there’s always the significant other to consider. David Cornwell, alias John le Carré, devised his pseudonym in 1958, on the same day he also created his most famous character, George Smiley, on the opening page of his first novel, Call for the Dead. This was when le Carré – a fresh recruit to MI5 and on his daily two-hour train commute into central London – ‘just began writing in a little notebook’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Shmith reviews 'A Private Spy: The letters of John le Carré' edited by Tim Cornwell

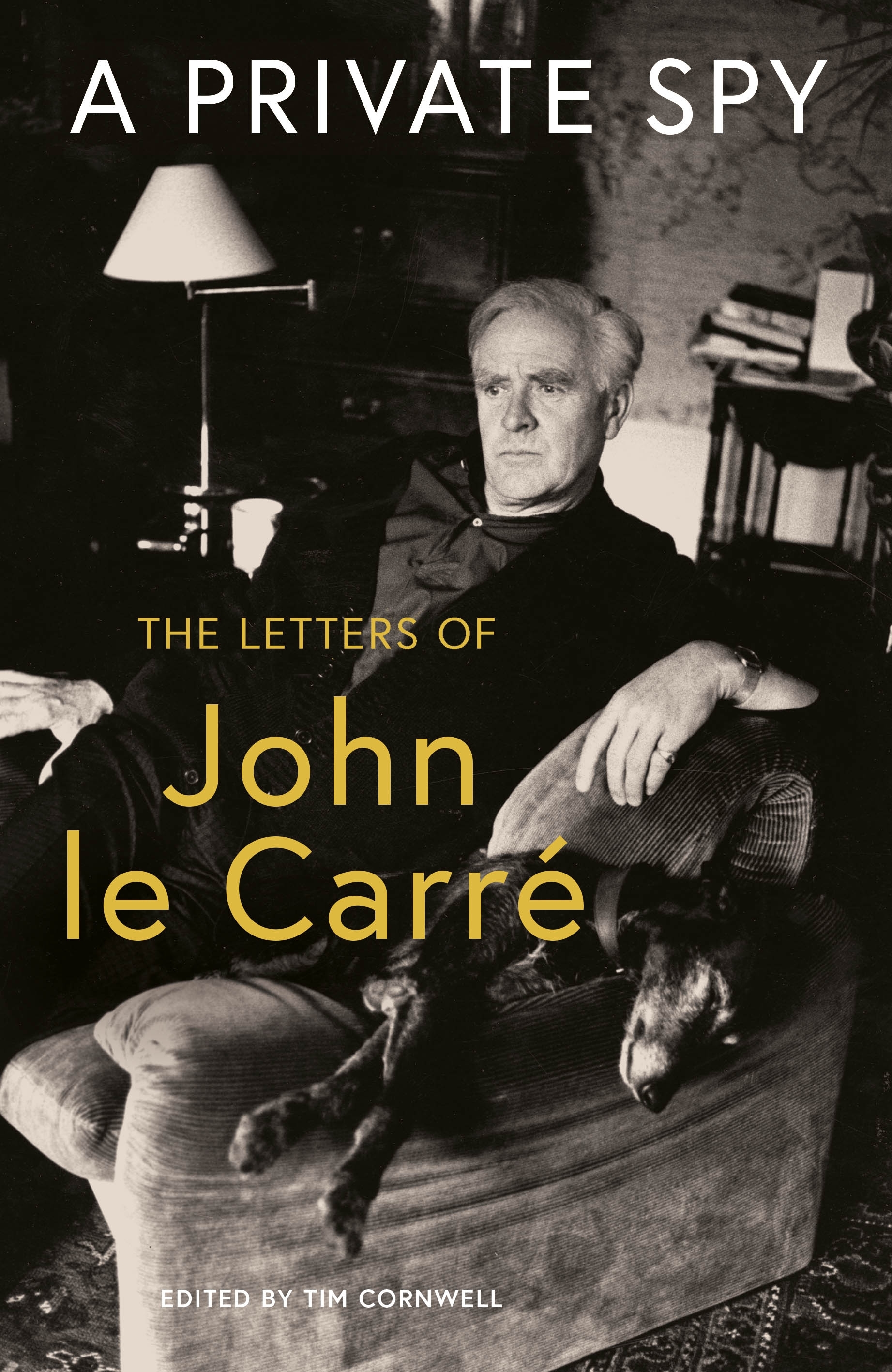

- Book 1 Title: A Private Spy

- Book 1 Subtitle: The letters of John le Carré

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $39.99 pb, 713 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

What, then, to make of A Private Spy: The letters of John le Carré? Are these – the author’s last words, so to speak – memoir or biography, and who is writing here: John or David? In truth, notes the book’s editor, le Carré’s third son, Tim Cornwell, his father, ever the agent of mystery, was having a bit each way. ‘There are letters […] in which David Cornwell is writing intimately and freely, while in others John le Carré is having a good look over his shoulder and laying down his legacy for posterity, as well as having some literary fun.’

Although, for a good two-thirds of his life, le Carré was a celebrated figure whose work was consistently popular and endlessly analysed, he was a man who shunned public attention. As we discover, via a 2009 letter to his new publisher, Penguin, le Carré’s long list of aversions included submitting his books for literary prizes, celebratory occasions, the ‘literary scene’, and ‘publicity anywhere in the world’. What other Englishman would turn down a knighthood and (far worse) an appearance on Desert Island Discs? But, then, he did commit the mildly treasonous sin of taking Irish citizenship just weeks before his death.

Fortunately, for the most part, le Carré’s letters are overwhelmingly buoyant, refreshingly perceptive, disarmingly honest, and always indicative of their writer’s prevailing mood. Some of the letters, just like their writer’s eyes, twinkle with wit and charm, while others, just like his famous bushy eyebrows, bristle with indignation and scorn. But one also finds humility and wistfulness: le Carré is not afraid to delve into his own complexities, especially his earlier life and his tortuous relationship with his wastrel father, Ronnie Cornwell. This con artist and occasional convict was the inspiration for the odious Rick Pym in le Carré’s masterly, semi-autobiographical novel A Perfect Spy (1986). Although its author flippantly referred to it as ‘the Daddy book’, Daddy remained, to him, someone to tolerate on occasion but generally avoid ‘until the next crisis, I don’t suppose there will be any trouble, or danger of seeing him’, le Carré wrote in 1957.

The writer within is always present in these letters: from young David’s schooldays in the mid-1940s right through to the last days of his life, when, from hospital, he typed on his iPad an email to his agent, saying, ‘In case we don’t get to talk, thanks for all of it.’

Some books of letters can appear almost as if their eventual publication was carefully planned while the ink was still drying on the notepaper. It is not certain that le Carré even wanted his correspondence published. Tim Cornwell merely says that the decision was made by the author’s estate – and thank heavens, thus entitled, Cornwell was able to set out on ‘a journey in my father’s company’. Here, it is sad to acknowledge that Tim Cornwell himself died suddenly in May 2022. His three surviving brothers write in a brief note: ‘[Tim] dived into the archive even when it hurt, [and] assembled narrative from chaos.’ How true. What could have been shambolic, in terms of subject matter, relevance, and continuity, is instead ordered, judicious, and eminently readable. Also included are some of le Carré’s drawings – a testament to his original intention to be an artist.

Throughout these seven hundred pages, it is easy to feel a sense of companionship, as if le Carré is writing not just to, say, Alec Guinness, Tom Stoppard, or Stephen Fry (among his coterie of valued friends), but to us, too. This is made even easier by the fact that le Carré wrote as he spoke, in that unmistakable, inimitable voice that can be appreciated on the self-narrated audio books of some of his works. You can almost hear those considered, drawling cadences taking shape within the elaborate rhythm of a single sentence. Take this example: ‘You have given so much light to our common language, so much dance and melody; you, listening so carefully to how you speak – and how they do. And you dramatise the perception so gracefully. So please take good care of our inheritance, and continue to add to it.’

These sentiments were expressed in a draft of a letter to the great American short-story writer John Cheever in 1982 (a letter the dying Cheever might well not have received). These noble and poetic words could equally have applied to le Carré himself.

Comments powered by CComment