Who would have guessed that a rejuvenation of regional difference might be triggered by a plague? Cosmopolitan Melbourne became the epicentre of what Prime Minister Scott Morrison has called the ‘Victorian wave’. Borders, the leitmotif of Australian politics since Tampa, suddenly became internal. My own state of Western Australia was sued for breach of the Australian Constitution for maintaining its ‘hard’ internal borders. Wonted barbs flowing between states now felt just a little personal. Interstate rivalry in Australia is not uncommon, with familiar stoushes over GST share, the Murray– Darling Basin, the location of naval shipbuilding, and the hosting of sporting events. But the idea that Australia has internal borders, not just to check fruit but to stop the movement of people, Australian people, is something that has only emerged with Covid-19.

I have been thinking about such things since I was appointed Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Western Australia in July of this year. With the decision not to renew the Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Sydney following Robert Dixon’s retirement in 2019, the position at UWA took on an additional significance within the AustLit community.

Within the national conversations in which I participate, I have always been conscious of my position as a Western Australian, but also quite unconscious of it as well. Like all unconscious things, we can only see them in certain deviations and hesitations, or in the bees in our bonnets. For me, when I speak about Australian literature I find myself wanting, in one way or another, to preface my remarks by noting the fact that I am speaking as a Western Australian. Look, I’ve just done it again.

It reminds me of those occasions when I become conscious of my accent. Like most people, I tend to imagine I have no accent. But my wife, who is Malaysian, sometimes teases me by repeating words I say, like ‘DVD’, which apparently I say as ‘doy-voy-doy’ à la Kath & Kim.

One of the notable features of Australian English is that it is not strongly marked by regional accents. Still, people do, as it were, think in regional accents. I say this even though it remains an open question whether settler Australia should be properly understood as being inflected by regional vectors. Yes, we are divided into states and territories, but are these anything other than lines on a map, drawn with a ruler and a set square, and the occasional river? The contrast between the political map of Australia and the now iconic AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia graphically exposes the poverty of the Australian regional imagination and the essential irreality of our territorial demarcations. More particularly, for someone like me, is it right to conceive of Australia in terms of literary regions?

My book Like Nothing on this Earth: A literary history of the wheatbelt (UWAP, 2017) wagered that there was a value in conceptualising Australian literature regionally. As much as possible I tried to emphasise the material factors at work in the agricultural colonisation of the south-western corner of the Australian continent, rather than invoking some genius loci that magically flowed into the veins of the writers that lived there. I remained sceptical about confected regional identities serving as euphemisms for white belonging. But still, something did happen to writers who lived their lives, often not their whole lives but some crucial part, in the wheatbelt. Apprehending what that was proved to be a major task in the book, but in the end I believe it does make sense and there is a value to speaking of these people – Dorothy Hewett, Jack Davis, Barbara York Main, John Kinsella, and the others I studied – as ‘wheatbelt writers’. They became, one might say, part of the wheatbelt complex.

Wheatbelt of Western Australia (Jana Schoenknecht/Alamy)

But what is regional difference? Certainly, one feels that regional difference is at most a weak factor when compared to the forms of difference that most occupy us today: race, gender, class, ethnicity, and, increasingly, sectarian political affiliations. The existence of regional difference as a literary concept was explored some decades ago in a remarkable conference that took place in Fremantle in 1978. The Fremantle Arts Centre, founded just two years earlier in 1976, hosted a roundtable discussion on ‘Regionalism in Contemporary Australian Literature’. The topic was the subject of lively debate, with presentations from Frank Moorhouse, Elizabeth Jolley, Jim Davidson, Thomas Shapcott, and others. The two main issues that emerged were whether regionalism could even be said to be present in Australian literature; and then, if it could, how regionalism was anything other than a glorified parochialism. I was only six years old when this conference took place, and living with my family in Munich at the time, so I am grateful that the presentations were later published.

Shapcott confessed in his postscript to the conference that he had initially thought the conference was ‘aimed at reassuring Westralians that they were OF US’, but came round to the applicability of the regionalist approach in more general terms. Davidson, as ever, was especially acute. He grasped something that has stuck with me since I first encountered it, because it provides a kind of litmus test for literary regionalism, at least as it was conventionally conceived: ‘The one ingredient most apparent in regionalism as a world-wide phenomenon is essentially lacking in Australia: grievance.’ Davidson gave the examples of Wales, Scotland, and the American South – vanquished peoples forced to live next to and among their wealthier conquerors. In the most direct terms, what Davidson was suggesting was that to be regional was to be a loser. That was not his judgement but rather him giving voice to a judgement hidden inside the fabric of regionalism. In that sense, more positive expressions of regionalism, including those I subscribe to, are also, at bottom, a means of compensation.

The great Marxist critic Raymond Williams drew a similar conclusion in relation to regions, although following a different line of reasoning from Davidson. For Williams, what emerged under the name of ‘regions’ in nineteenth-century Britain was essentially a geographical spatialisation of class. Regions were economically subservient peripheries of production. This meant that, for Williams, regional consciousness was a form of class consciousness. With this in mind, it is interesting to go back to how accents work in Australia, where they follow class rather than regional lines.

No doubt, contemporary Australia is well seeded with the politics of grievance. But Davidson is largely correct to suggest that this has not typically found its expression in regional particularity, at least not in such a way that it then gave expression to what might be called an imaginary. Davidson did proffer one possible exception: the case of Tasmania. Indeed, his later, highly influential 1989 Meanjin essay ‘Tasmanian Gothic’ was a seminal attempt to delineate a regional Tasmanian literary sensibility, one that was indeed founded in grievance.

The papers at the Fremantle Arts Centre were published in Westerly’s December 1978 issue. The magazine was at that time edited by Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan, who were strong advocates of literary regionalism. I only have faint memories of Cowan, but I was taught by Bennett at UWA as an undergraduate and remember his particular interest in regionalism in Australia and America, but also, presciently, in the Southeast Asian ‘region’ and the Indian Ocean rim. Cowan was one of my case studies for Like Nothing on this Earth. Going through boxes of his papers and personal effects held by the Peter Cowan Writers’ Centre, I came across a letter he had written to his wife, Edith Howard. The letter was undated but probably written in 1941. In it he defended his desire to write a ‘regional novel’ based on his experience of working as a rural labourer in the wheatbelt through the Depression years:

I can see what you don’t want me to do. You don’t like the idea of a regional novel, and I am quite determined to write only regional novels until I have a quite different type of experience. I will probably never have this, but that will also probably not stop me trying regional novels. Look at the American regionalists – definitely successful. I think that regionalism is something the Australian novel needs.

In the history of Australian literary regionalism, this letter will be an important document, for it is one of the earliest explicit announcements of this literary goal. There was clearly regional writing before 1941, but I haven’t come across it being described as such. Cowan’s main influences at this point were Thomas Hardy, William Faulkner, and John Steinbeck, but what one notices when reading Cowan’s often exquisite short stories is something quite different from these writers. Instead of the swirl of broken histories that eddy through his American and British exemplars, in Cowan’s writing there is a poetics of isolation that is coupled with a profound historical amnesia.

Why? For the simple reason that Cowan’s sketches take place in the midst of colonisation – the agricultural colonisation of the south-west of the Australian continent – rather than in its wake. In his later writing life, Cowan would become an important historian of the Swan River colony, but at that point in his career he was trying to capture something different, some particularity of sensibility that was already ingrained in the raw wheatbelt farms he had laboured on, and which had so recently been carved out of their ancient human and ecological systems. These farms proceeded in violent disregard of what went before, and when Cowan came to express this he found himself, I can’t put it more precisely, at a loss. All his characters are like this – they are at the end of things.

Arguing for a relationship of literature to place in Australia is not in itself new. The Oxford Literary Guide to Australia (1987), edited by the late Peter Pierce, was a pioneering work of literary place-making. Philip Mead, my predecessor in the UWA Chair, has written eloquently on literary regionalism. Cheryl Taylor, with her work on North Queensland, was one of the first academic literary scholars (along with Bruce Bennett) to take literary regionalism seriously. In the 1990s, the rise of ecocriticism gave particular attention to the concept of a bioregion, opening up the possibility that literary regionalism might be reimagined as literary bioregionalism. One can see this emerging in some of the fine literary scholarship on the Mallee districts of Victoria by Paul Carter, Brigid Magner, and Emily Potter. Like Carter, Stephen Muecke has also been adept at utilising the post-structuralist resources of European literary theory (de Certeau, Latour) to unstitch the people and places of the Australian continent from the weave of colonial predeterminations.

Cutting back across the emergence of bio-regionalist sensibilities in literature and criticism has been the advent of second-wave Indigenous authors like Alexis Wright, Kim Scott, and Tony Birch and of the powerful insinuation of the concept of ‘Country’ into wider Australian discourse. The fact that Country does not coincide exactly with bioregion – though they often speak to each other – opens up deeper epistemological differences that remain to be negotiated. No one is necessarily clamouring for a rebooted Jindyworobak syncretism, but there might yet be some value in a genuine dialogue about the spiritual (or in the current parlance, more-than-human) value of environment.

For me, literary regionalism is a critical stance that I find myself adopting, whether I want to or not. I think it is just something that happens when I read, and I would feel uncomfortable advocating for reified regional schools of expression. It does produce interesting results. In my book, I found that major writers like Dorothy Hewett, Jack Davis, and Elizabeth Jolley took on different complexions when they were viewed through the prism of region.

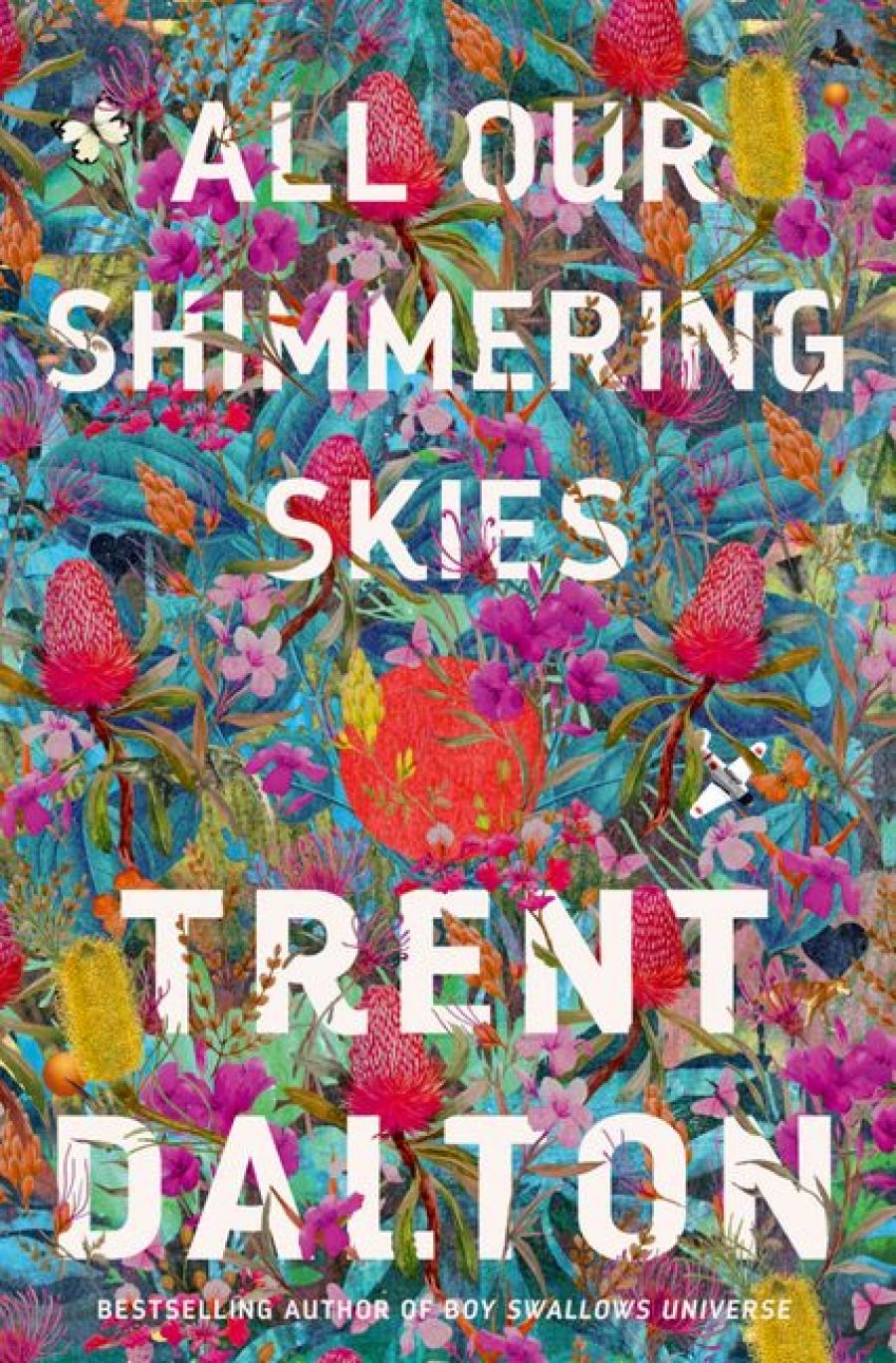

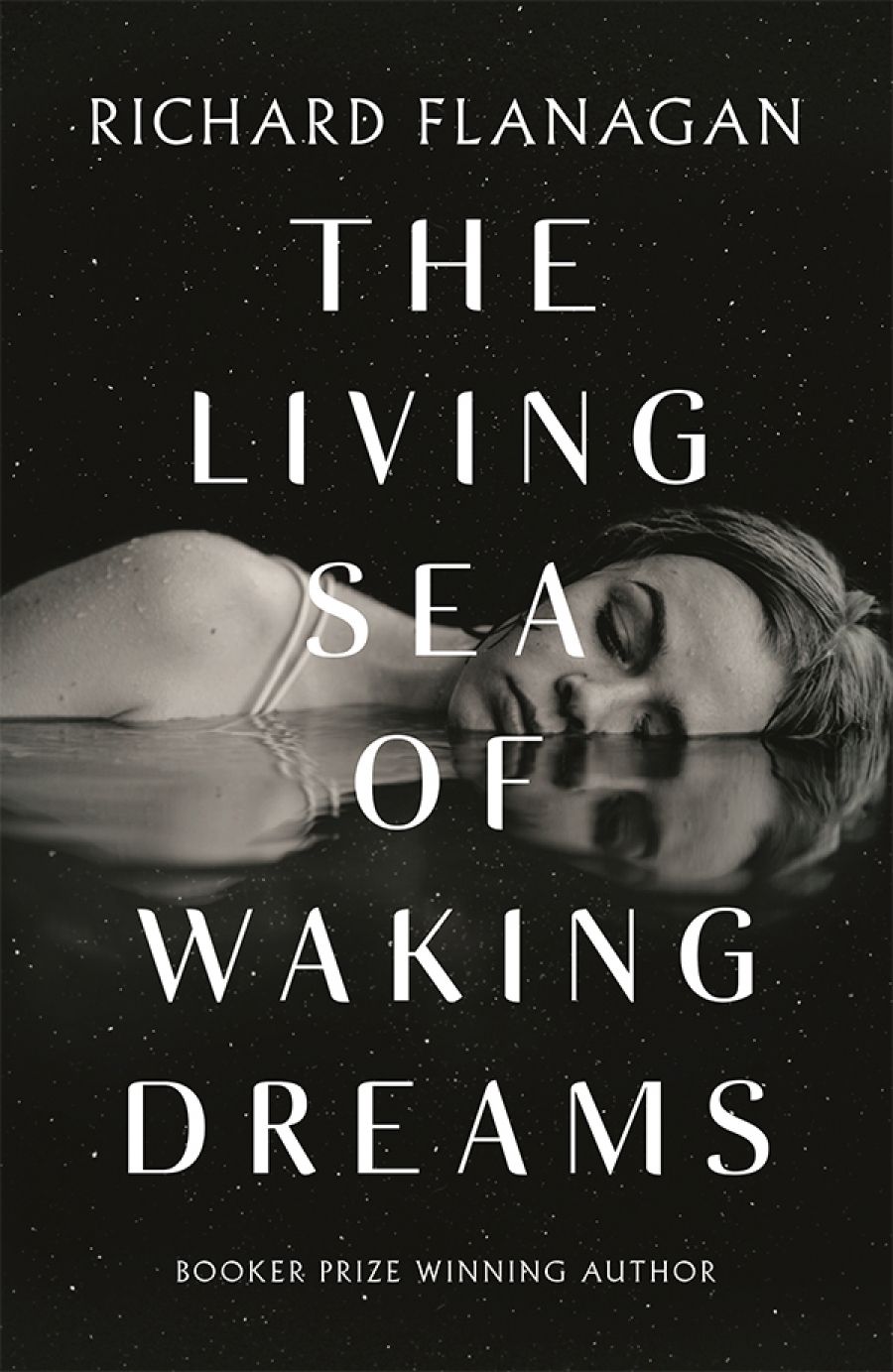

In similar ways, I find myself relating to Alexis Wright, Kim Scott, Judith Wright, Richard Flanagan, Thea Astley, Colin Thiele, Charmaine Papertalk Green, and Trent Dalton as regional writers. It is not a label they would necessarily accept or welcome, and they would have different reasons for being wary of such designations. If this group are all regional writers, we must wonder if they are not then somehow differently regional. In my neck of the woods, it has been inspiring to watch the Wirlomin Noongar grouping (Kim Scott, Clint Bracknell, Claire G. Coleman, and others), who trace their belonging to the south coast of Western Australia, become a nodal point of Noongar cultural and language renaissance, and seriously influence the national imaginary. I realise that this might be of a different order to a regionalism we might ascribe to Judith Wright or Thea Astley, but I think just entering into the world of regional difference opens us to the possibility not just of different regions, but of being differently regional.

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

.jpg)