- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chequerboard forests

- Article Subtitle: John Blay on walking with intent

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her paean to walking, Rebecca Solnit notes that any history of walking is by nature provisional. As a subject it trespasses almost infinite fields: ‘anatomy, anthropology, architecture, gardening, geography, political and cultural history, literature, sexuality, religious studies’. Despite such ungainly dimensions, her book Wanderlust (2000) maps rich connections between walking, thinking, and creativity. These stretch from the peripatetic philosophers of ancient Greece to the Romantic poets; from Walter Benjamin on Parisian streets to political protesters crossing no-go zones.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

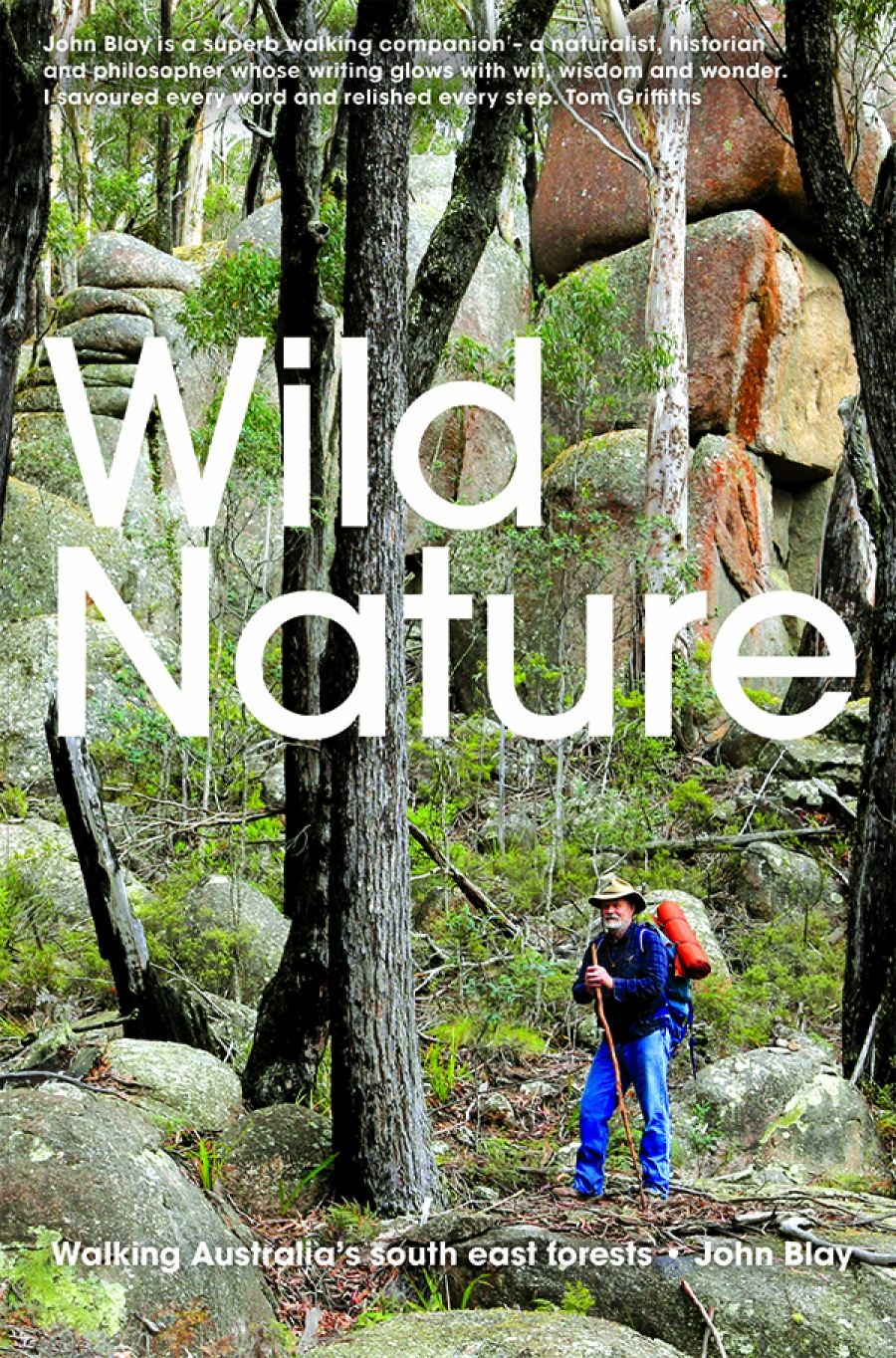

- Book 1 Title: Wild Nature

- Book 1 Subtitle: Walking Australia’s south east forests

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 349 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/dxGd3

Escarpment country becomes a liminal zone ‘where the divide between tablelands and the coast is braided into wild gorges and cliffs’, difficult, sometimes fearful, lyrical, housing botanical treasures, also obsession-forming. A few paths exist east to west, but none runs north to south. Blay decides to forge his own ‘trails’. Accompanying him is Jacqueline, fervent about the landscape but less than enamoured, she discovers, of bushwalking.

Wild Nature belongs to a long if amorphous tradition of walking with intent

The trails assume many forms: animal tracks, geological formations, GPS routes, ‘deep trails’ of Aboriginal custodians (mapped assiduously in On Track), waterways (John and Jacqueline plummet down precipitous gorges and gullies in torrential rain and semi-darkness), passages of rare acacia species, through misty forests, and waratahs in bloom, and something as banal as a ‘rat trail’ gnawed into their food supplies.

At the heart of Wild Nature is a puzzle: ‘the question of how places are reserved for nature and protected’. People are compelled by something: an animal, a plant, or an entire landscape. ‘Where one person sees the value, others are likely to agree, and where officialdom also recognises the value, that locality is likely to be protected. That “value” or magical ingredient must be one of the great mysteries of nature.’ Above all, the terrain Blay walks is timber-felling country. He brings to life numerous local battles fought to protect the south-eastern forests through a range of national and state parks and reserves. Amid the book’s descriptive natural history passages come voices of dissent against a timber industry that is speaking ‘as one’ with regulatory and management bodies including the NSW Forestry Commission. Other works have tackled vexed woodchipping histories in the region, among them an informative chapter in Mark McKenna’s Looking for Blackfellas’ Point (2002). As a long-term resident, Blay draws on local knowledge to provide more personal glimpses into the ‘forest wars’. We meet long-haul protestors who have sacrificed their health to the cause, and individuals of various political persuasions stirred by their principles to fight. A ground-breaking, Aboriginal-led petition in the 1970s against the destruction of sacred stones on Mumbulla Mountain north of Bega is memorable. Earlier, other sacred stones had been blasted to erect a telecommunications tower on the mountain, a grim reminder of the litany of precursors to Rio Tinto’s recent desecrations in Juukan Gorge.

One of the real strengths of Wild Nature is its determination to bear witness and pay tribute to these troubled lands. Blay walks a chequerboard of forests – some exemplify the ‘wild nature’ he craves, beyond the most destructive marks of human activity. Some resemble memorials where enormous tree stumps stand ‘like gravestones’ amid scrubby, post-logging regrowth, ghosts of the old forest. Others are freshly bulldozed grounds that bring to mind Benjamin’s World War I battlefields lying mangled ‘under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds’.

Wild Nature is bookended by fire – not the controlled, mosaic-like burning of old practised by Aboriginal people and early farmers – but the conflagrations of last summer fed, climate scientists say, by global warming. As Blay pens his preface, the view through his Eden window glows crimson. A cluster of conventional nature photographs – close-ups of flowers, vistas from mountain tops, native animals – is disrupted by one image in the close tonal range of a smoke-muted landscape. On the horizon, the infamous chipmill on Eden’s harbour is consumed by flames. Blay’s afterword is a journal of fire so immense that by midday ‘lights are necessary to see anything inside the house’, and in an uprush of superheated air pyrocumulus clouds form overhead. Rain born of fire dampens his lawn.

Many despaired at the mass destruction of forests and fauna last summer. Meanwhile, in the fires’ aftermath, logging in New South Wales and Victoria has continued apace in both remnant unburnt habitat and fire-damaged forests. Why one form of destruction is so lamentable, while the other raises barely a collective murmur, is a quandary implicit in Blay’s walking tales.

Other threads in the braided narrative add levity to such questions. Even the two central figures cannot quite agree. French-Australian Jacqueline decides she cannot, will ‘NEVAIRRR’ become a bushwalker, preferring to appreciate the forest on her own terms. Blay continues on foot; she meets him at intervals with supplies. They miss appointments, experience frustrations and mishaps. Nevertheless, they find a mutual way, a provisional accord punctuated by moments of nature-inspired ‘ecstasies’. Wild Nature’s larger questions – how not only to ascribe value to but also to protect Australia’s diminishing forests – may have been stalled by the Covid-19 crisis. They are bound to resurface, though, when temperatures begin to warm and we head into a new summer.

Comments powered by CComment