- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Places within

- Article Subtitle: Confronting the legacy of abuse

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

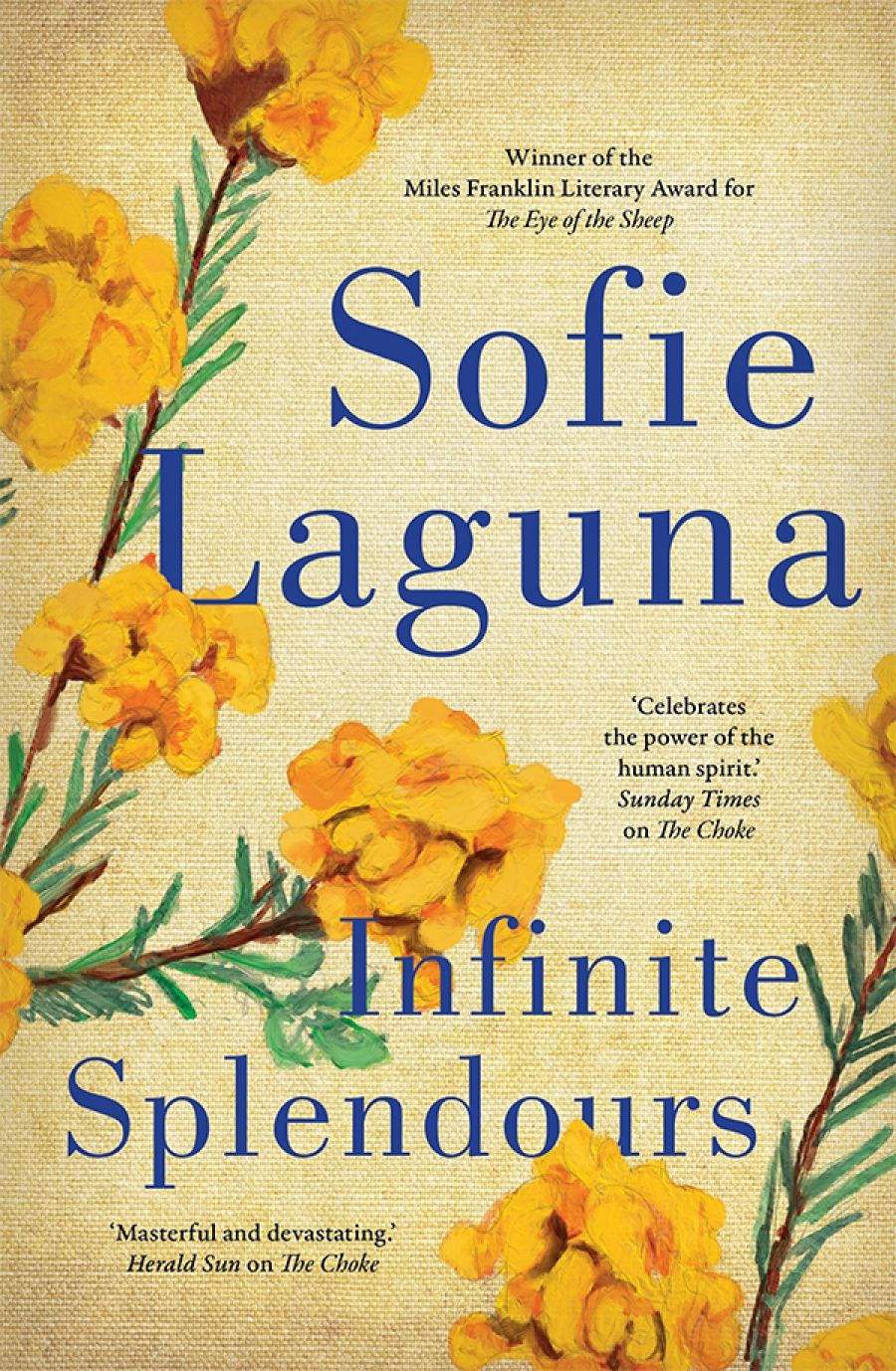

Sofie Laguna does not shy away from confronting subject matter. Her first adult novel, One Foot Wrong (2009), is about a young girl forced by her troubled parents into a reclusive existence. Her second, The Eye of the Sheep (2014), which won the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2015, tells the story of a young boy on the autism spectrum born into a family riven by poverty and violence. Her third, The Choke (2017), concerns a motherless child in danger because of her father’s criminal connections. Infinite Splendours is also about the betrayal of a child by the adults in his life, but here Laguna ventures into new territory, exploring the lasting impact of trauma on a child as he becomes a man, and whether the abused may become the abuser.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Infinite Splendours

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 436 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/yzkYN

When the book opens, in 1953, Lawrence is a bright little boy who does well at school, has a passion for art, and is the apple of his mother’s eye. Despite the absence of a father, theirs is a happy family. Lawrence is protective of his sporty little brother. Louise works hard at the local dairy to support them and is a loving mother, if a little distant – ‘even if Mother was close … she kept a part back, and that was the part we wanted’. The boys are aware of some darkness in her past which she hints at but does not explain.

One day a man from Louise’s past turns up and inveigles his way into the lives of the family. Worldly and charismatic, he shows an interest in the boys, playing sport with them and giving them gifts. Lawrence is very taken by him, realising for the first time that there had been an absence in their lives – ‘we had been missing a man’. That man betrays Lawrence’s trust in the worst way imaginable, destroying his ‘careless boyhood’ and shattering his life.

The rest of the book is about the catastrophic impact on Lawrence of that violation. Laguna is unsparing in her depiction of the disintegration of Lawrence’s identity: ‘I was nothing,’ he says in the immediate aftermath. ‘I felt myself dividing; there were two selves to choose from. One inside, one outside.’ Lawrence develops a bad stammer and is unable to concentrate at school, limping through the remainder of his school years, taunted by the other students. ‘I was separate; from school and from learning … and from myself.’ Haunted by guilt and shame, Lawrence suffers debilitating physical symptoms as well as this psychic pain. For the rest of his life, he grapples with abdominal problems.

Lawrence’s relationship with Paul is irreparably damaged. When Paul, who has his suspicions, asks Lawrence what happened, Lawrence turns on him viciously. In a role reversal, Paul becomes his older brother’s protector, defending him against the school bullies. Lawrence’s relationship with his mother is shattered as well. Performing poorly at school and barely able to speak, he is no longer her pride and joy, and she infantilises him; when he leaves school she gets him a job in the dairy, speaking for him at the interview. ‘It was as if she thought I was ten years old and could do nothing for myself.’

As an adult, Lawrence retreats into a life of solitude. After a loss, he lives alone in the family home. Paul, who brings him monthly supplies, becomes his sole contact with the outside world. The only things that bring him solace are painting, which he returns to with a vengeance, walking in nature and listening to his beloved Madama Butterfly. ‘I too had places within me … Painting took me to those places; and Butterfly, and beer. Walking up the mountain.’

Lawrence has no friends – with two significant exceptions. Here the story becomes especially confronting, and Laguna’s psychological acuity is displayed to full effect. On two occasions the adult Lawrence attempts to befriend a ten-year-old boy. The first of them, Colin, whom Lawrence meets at twenty-four, is the son of a dairy worker. Lawrence meets James, the second, when he is fifty-one and James’s family moves in next door. Lawrence’s attempts to befriend each boy are pathetically similar: he starts by conversing (haltingly), then proffers gifts, then becomes consumed by a longing which he expresses by painting the boy. Laguna (deliberately) ventures into dangerous territory here. While the reader feels sympathetic towards lonely Lawrence’s awkward attempts at friendship – ‘I have been alone and I am no longer alone’– at the same time she feels apprehensive about Lawrence’s feelings, which veer towards the obsessive. Will the child victim turn into the adult predator? Whose fault would it be if he did?

I suspect that Infinite Splendours will invite comparisons with Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, published in 2015. Like that extraordinary book, it looks unflinchingly at the lived experience of child sexual abuse, in particular its enduring legacy. As Laguna demonstrates so powerfully, the abuse often destroys not just a child’s past and present but also his or her future.

Comments powered by CComment