- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ripple effects

- Article Subtitle: Pinpoints of life experience

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A short story collection can have much in common with a collection of poetry, where each story pivots on attention to something particular and arresting – an image, a memory, the encounters with strangeness or beauty that can occur in a life. Individual stories build delicately towards such a moment, then fall away quickly, willing a reader to engage with feeling and suggestion rather than the comprehensiveness of narrative.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

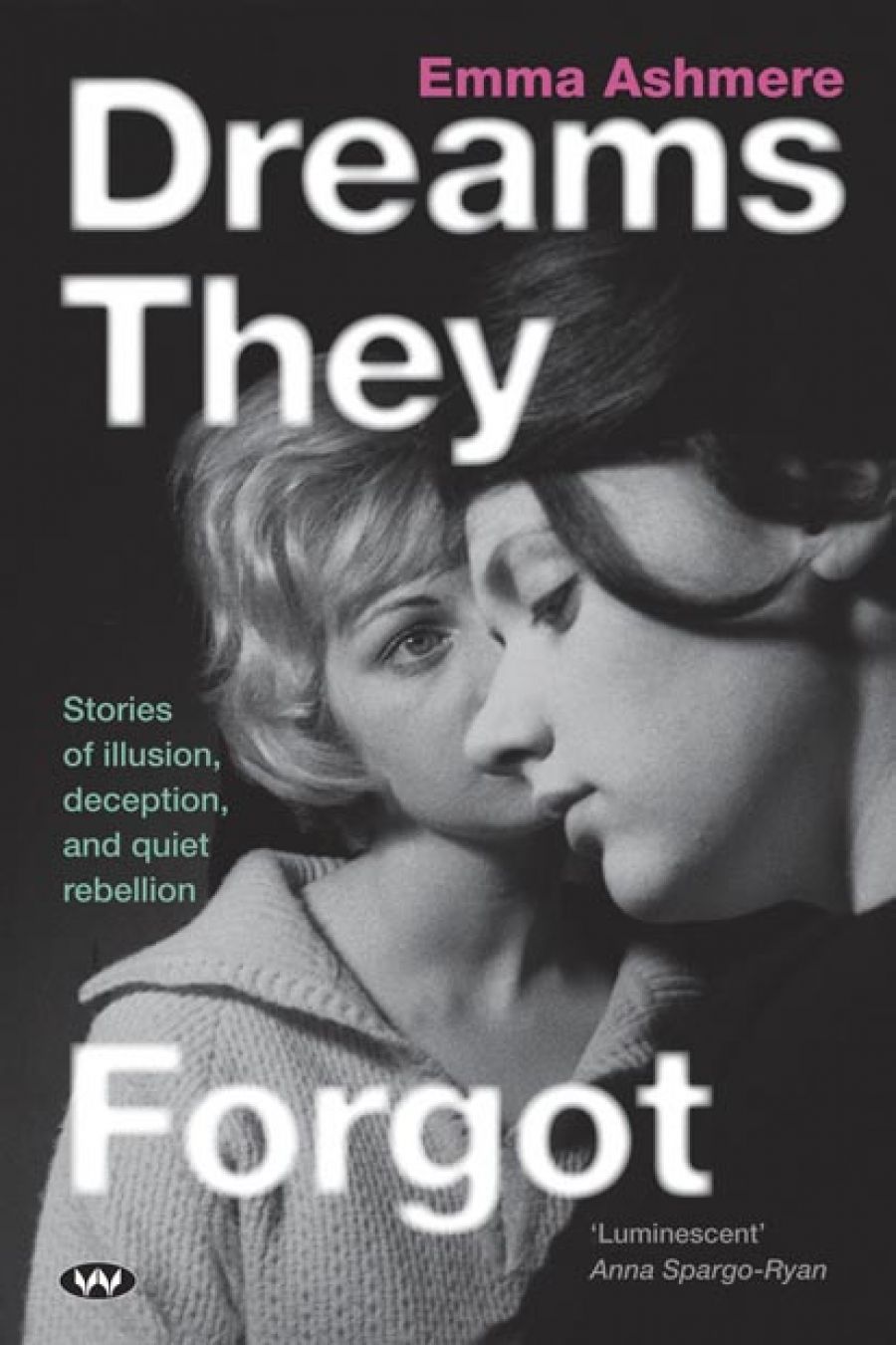

- Book 1 Title: Dreams They Forgot

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $24.95 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MZb7M

The leitmotif of Ashmere’s collection (her first, following her début novel, The Floating Garden [2016]) is the point of view of the outsider, the character who often feels both inside and outside of a conventional social frame. This can be seen in a number of ways across the stories. For instance, in ‘The Ends of the Earth’, the speaker is increasingly fractured by an encroaching dementia as she tries to make sense of her own ancestor’s dislocation in colonial Australia. The narrator of ‘Trick of the Eye’ looks back as an adult at her difficult and traumatic childhood as a way of understanding her sense of struggle; in ‘A Thousand Eyes’, a child raised in an environment of loss, paranoia, and isolation must come to some reconciliation with a new sense of herself in a previously unrecognised world. The unnamed speaker in the first story, ‘The Winter Months’, is alienated by her intense social anxiety, her seeming inability to cut through a haze of confusion to find a path in life, and her attraction to the beautiful but troubled Aveline.

The longing for another woman, often unarticulated and complicated by the uncertainties of youth, is a recurring theme across the collection. Ashmere celebrates the possibilities of love and tenderness between women while also giving us a sense of the historical difficulty facing such couples, especially in the context of familial and social expectations. She shows us a number of perspectives onto this. ‘The Second Wave’ combines personal narrative with politics as the two women characters, who have been on the edge of the narrative, leave the family environment and make their way in Adelaide to support Don Dunstan’s decriminalising of homosexuality. From the point of view of the sister who narrates this story, we see how the elements of uneasiness and straining at expectations are finally made sense of when the two women leave together. ‘Silent Partner’ traces the obscuring of same-sex partnerships across time and family history, as present-day family members reinstate the love hidden behind the term ‘great friend’ to ‘life partner’ on the family tree. Similarly, ‘Standing Up Lying Down’ is in many ways the story of the emergence of love as Laurie meets Romaine and their relationship travels from a chance meeting in the Carlton Gardens to domestic commitment in a tender and understated narrative of romance. However, as Laurie becomes increasingly disabled, this is also a powerful story of a changing relationship to one’s body – to what it can and can’t do and how that might impact on an understanding of self and the world.

This shift in relation to a previously held sense of identity is also traced across a series of stories that deal with the ongoing dislocations of trauma. In ‘Warhead’, the battlefields of France have psychologically scarred a schoolteacher, and the ramifications of his unresolved suffering in turn affect his young and impressionable student. In ‘Seaworthiness’, Arthur Morris attempts to shake off his own wartime pain by leaving his fiancée and working a ship to London; however, the trauma of the rigging and the storms of open sea only entrench his emotional distress and isolation.

In the final story, ‘Fallout’, the narrator speaks from both child and adult perspectives to trace her father’s PTSD and physical illness as a result of involvement in the Maralinga nuclear tests. Not dissimilar to the erasure of Great Aunt Harriet’s ‘dearly loved’ in ‘Silent Partner’, Cyril’s experiences in the outback have been elided, not allowed to be spoken of or recognised in the powerful interests of political and colonial expediency. As the narrator recalls her father’s tortured efforts to speak and to name what had occurred before he succumbs to illness, she herself comes to see the shocking reality of these events, the cavalier ‘Turn around chaps. Shut your eyes. Cover your face.’ It is her rendition of their story that finally does the work of bringing the unspoken and unrecognised into the shape of viscerally felt life events, the sphere of a publicly shared discourse and experience.

Ashmere’s stories offer moments of insight into love and alienation, the attempt to integrate the fragmentary nature of childhood into the construction of the adult ‘self’, and the struggle to find ways to manage the ripple effects of trauma; they are also crucially concerned with the development of the voice to tell it. In a Grace Cossington Smith moment, two young women challenge convention and drive to Sydney to paint the almost-completed Harbour Bridge in ‘The Sketchers’; ‘Portrait or Landscape’ traces the development of a young woman from unfocused youth to a poet; ‘A House Divided’ gives us a historical narrative of a child’s transition from grief, via the kindness and mentoring of a neighbour, to the possibilities of finding her own expressions in art.

In their different ways, all stories in this collection signal the importance of finding the individual experience that cries out to be articulated and acknowledged while also refining the craft required to make it sing.

Comments powered by CComment