- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The histories that shape us

- Article Subtitle: In search of the author’s father

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

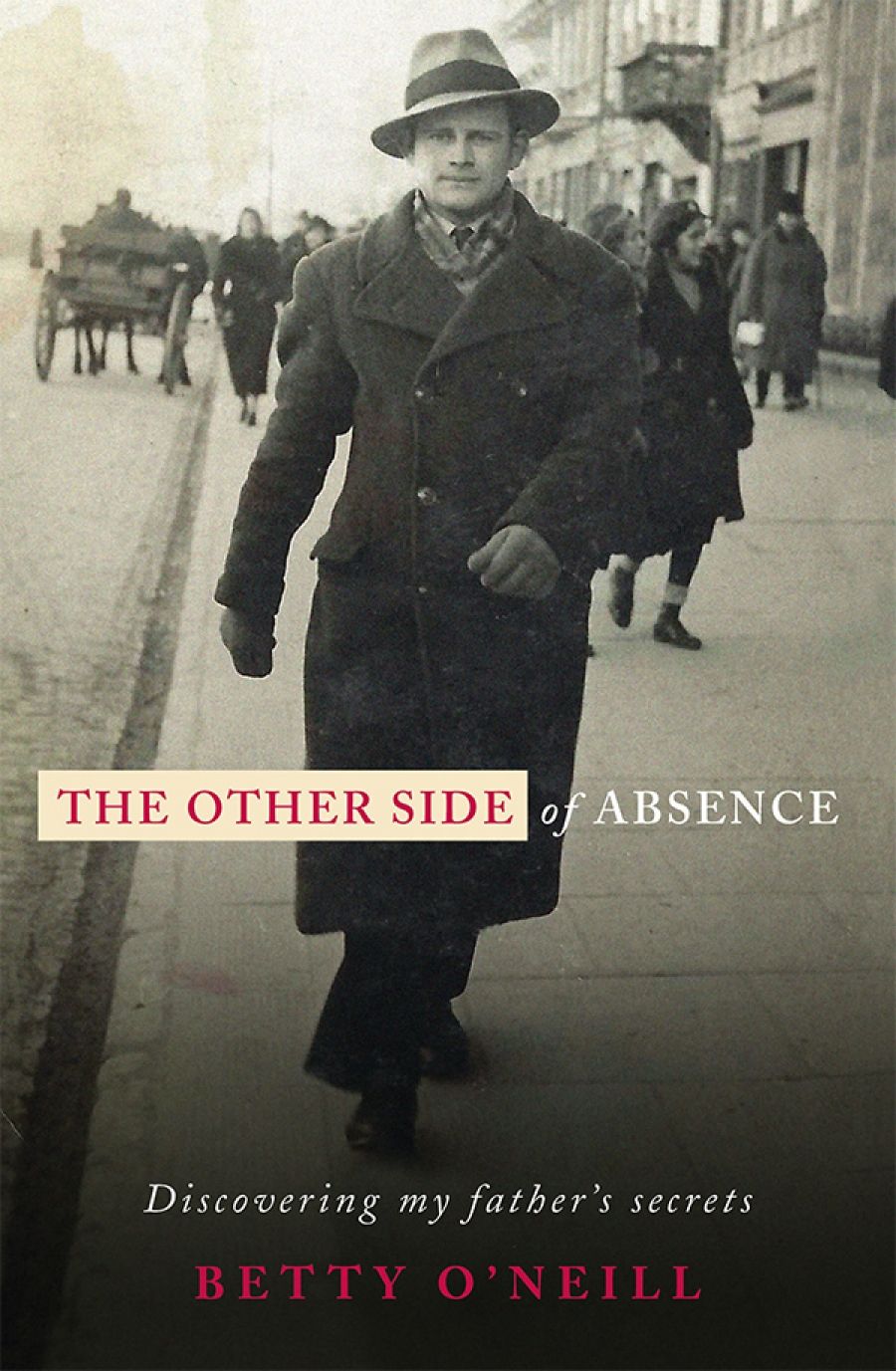

The realisation that our parents are not exactly who we understood them to be can be a profound rite of passage. For some it comes with no forewarning: a random event leads to an accidental disclosure, or substantiates an old rumour. For others this realisation takes shape in a less acute though no less transformative manner. With The Other Side of Absence: Discovering my father’s secrets, Betty O’Neill pieces together her family history in an effort to learn more about her father, a stranger she briefly encountered when she was nineteen. What began as an innocuous exercise at a writers’ retreat would evolve into a three-year research project through which the author uncovers the riveting story of Antoni Jagielski – resistance fighter, Holocaust survivor, unsettled postwar migrant, and absent father.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Other Side of Absence

- Book 1 Subtitle: Discovering my father’s secrets

- Book 1 Biblio: Ventura Press, $32.99 pb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Eky6n

Structured around three main sections, The Other Side of Absence is at once a family history, a fieldwork diary, and a personal journal. O’Neill opens with an account of her own formative years, foregrounding the challenges her mother, Nora, faced as a single parent in Australia during the 1950s and 1960s, before turning to the story of her father. A member of the Polish resistance movement during World War II, Antoni was captured by the Germans in 1941 but miraculously survived four years in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Mauthausen–Gusen. After the war ended, he joined the remains of the Polish army under British command in Italy and eventually transferred to England as a political refugee. In London in 1953, he would meet Nora, who had travelled from Australia for a working holiday. The couple soon married and moved to Australia with their newborn daughter. Their life as an Australian family would, however, prove short-lived: almost as soon as they arrived, Antoni disappeared. O’Neill would reconnect with her father as an adult briefly and sporadically in the months leading up to his final return to Poland in 1974, with these awkward encounters reinforcing a sense that he would forever remain a stranger to her.

Nature abhors a vacuum, and so too does the human mind. Lingering on the margins of her consciousness for decades, O’Neill’s urge to fill in the missing details of her father’s story became all-consuming in the spring of 2011 with Nora’s death. The book’s second section is anchored in her desire to reconstruct Antoni’s life, a process that begins with just a pair of old photographs, complemented by a few identification documents found among her mother’s possessions. Fortunately, this modest body of evidence proves sufficient, and in this sense the book owes a great deal to the intellectual infrastructure upon which it rests. This includes Polish organisations that safeguard the history of what was the largest national group of migrants to Australia after World War II, Jewish archives and museums across the country, local historical societies, and, ultimately, Australia’s strong tradition of academic research into the history of migration. Certainly, The Other Side of Absence demonstrates the vital role that these knowledge networks play whenever we seek to uncover and understand our past.

O’Neill’s investigation culminates in a research trip to Poland, which takes place predominantly in the eastern city of Lublin, where Antoni had been raised. Here the author seeks to untangle the story of her father’s wartime life, along with that of his other family – a wife and daughter he had been forced to leave behind. In joining a resistance movement loyal to the Polish government-in-exile in London, Antoni became a target of both the Germans and the Soviets. After the war ended, his military past made it dangerous for him to return to communist Poland. Yet, as O’Neill discovers, her father managed to remain in contact with his Lublin family throughout his years in Britain and Australia, and ultimately reunited with them after thirty-three years in exile. This dramatic account of two antipodal families – one in Poland, the other in Australia – connected by the figure of an absent father is, however, somewhat burdened by descriptions of the research process itself. Indeed, the rigmarole that frequently underpins historical research, from locating sources and interpreters to dealing with uncooperative archivists, too often interrupts an otherwise intriguing central narrative.

Elsewhere, broad descriptions of what is an immensely complex and still contested history undermine the effort to contextualise Antoni’s story. This leaves critical points in the narrative unresolved, including the question of how political circumstances permitted Antoni to return to (still-communist) Poland in the mid-1970s, a time when members of the Polish resistance movement were still treated with suspicion. In also omitting any critical engagement with the politics of memory, O’Neill’s account misses the opportunity to explore how attitudes towards personal and official memories of World War II have shifted over time.

In the book’s final section, the focus returns to Australia and the author’s mental, moral, and emotional effort to make sense of what she had learned in Poland, and her own position within this intricate web of familial ties. The figure of the father O’Neill discovers is someone who remains difficult for her to connect with: a wartime hero, a survivor of unimaginable atrocities, but also a master of disguise and obfuscation, whose allegiances often remain ambiguous.

The desire to discover her father does, however, ultimately forge a new sense of belonging and historical grounding: both through her discovery of an extensive Polish family (her father had five siblings) and her participation in the communities established by families of Holocaust survivors. An honest and emotional account of how families shape us even in their absence, O’Neill’s story will be a treat for those partial to family histories, and provides a timely reminder of how our personal circumstances are so profoundly shaped by global events.

Comments powered by CComment