There is a difference between celebrity and recognition. Celebrities are recognised in the street, but usually because of who they are, or who they are supposed to be. To achieve recognition, however, is to be recognised in a different way. It is to be known for what you have done, and quite often the person who knows what you have done has no idea what you look like. When I say I’ve had enough of celebrity status, I don’t mean that I am sick of the very idea. As it happens, I think that the mass-psychotic passion for celebrity – this enormous talking point for those who do not really talk – is one of the luxurious diseases that Western liberal democracy will have to find a cure for in the long run, but the cure will have to be self-willed. I don’t think that it can be imposed, and certainly not from the outside. I didn’t much like Madonna’s last television appearance in Britain. Billed as the height of sophisticated sexiness, it featured Madonna wearing high heels, a trench coat, and a beret. She crouched like a pygmy prizefighter while snarling into the microphone as if anyone listening might be insufficiently intelligent to understand her message – a hard audience to find, in my view.

I thought of this performance as an attempt to prove that a knowing sneer can be made audible while discrediting the French Resistance. But Madonna’s slow paroxysm of self-regard, a flagrant example of Western decadence though it undoubtedly was, did not inspire me to fly a hijacked airliner into her house. Here, indeed, was a celebrity gone mad, if not celebrity itself gone mad. But she will have to realise that herself, through her sense of the ridiculous, if she still has one. A violent attack would produce nothing but more Madonnas: spiteful spores in berets. An awareness even more sophisticated than the aberration is its only cure, for her and for the phenomenon of celebrity as a whole. Until the moment when mocking laughter does its work, we will be stuck with celebrity being called a phenomenon, or, as even the journalists are now quite likely to call it, a phenomena. Really, it is just a bore. But to know that, you have to be genuinely interested in the sort of achievement whose practitioners you feel compelled to recognise in a more substantial way. The cure lies in that direction if it lies anywhere.

Clive James and Peter Goldsworthy at the 2003 La Trobe University/ABR Annual Lecture in Mildura on 25 July 2003

Clive James and Peter Goldsworthy at the 2003 La Trobe University/ABR Annual Lecture in Mildura on 25 July 2003

While we are waiting for the cure, I am quite content to go on having my life distorted by my own small measure of celebrity, which has mainly come about because my face was once on television. Your face doesn’t have to be on television for long, and in any capacity, before you become recognisable not just to normally equipped people but to people who are otherwise scarcely capable of recognising anything. You will find out why posters of the ten most wanted criminals can be so effective. How is it that the lurking presence of a fugitive master of disguise is so often detected by the village idiot? The answer has to do with a primeval characteristic of our sensory apparatus. Once the human brain has the outline of another human face sufficiently implanted, that other human face can be picked out of a crowd decades in the future, whatever has happened to it. Once you have appeared on that scale, nothing is harder than to disappear. On the day you realise that you can vanish only through never emerging from your motel room, and that even then the pizza delivery man has recognised you through your floor-length facial hair, you will realise that celebrity really amounts to a kind of universal mugshot. While it resolutely misses the point of what you would like to think you have done, it is an indelible picture of who you are.

But when I say that I have had enough of it, I only mean that I have had my share, and can’t complain. Some of the distortions were always welcome. That was one of the things that made them distortions. They were too welcome. You can very rapidly get used to the idea that the swish restaurant will always find a table for you. You can get so used to it that you think the restaurant needs a new manager on the night when the table strangely can’t be found. What’s needed, of course, is not a new manager for the restaurant but a new injection of fame for yourself. Now there’s a distortion. That way madness lies, and madness would probably have arrived for me if I had ever been a famous young rock star: go to hell, go directly to hell, do not even pass through rehab. As it happened, I was never a famous young rock star. Instead, I was a reasonably well-known middle-aged media man, and never became addicted to anything more destructive than Café Crème mild miniature cigars, smoked at the rate of one tin of ten a day, escalating to two tins the day after I passed the insurance medical. When Elvis Presley hit bottom, he exploded in the bathroom. His bottom hit the ceiling. My own nadir was less spectacular, and the world did not take note, because the world did not care.

I was in one of the smoking rooms at Bangkok Airport, on the way to Australia. I would say you should see a smoking room at Bangkok Airport, but in fact you can’t see it, or anyway you can’t see into it. It is not very big, and, though made of glass, it is opaque when viewed from the outside: opaque because of what is happening inside. The smokers are in there, jammed together like the damned on some broken-down, fogbound trolley car designed by Dante. When a smoker, reaching for the smokes in his pocket, opens the door to enter, he realises that he can leave the smokes where they are. All he has to do is breathe in. It was my last experience of this that made me realise that I should leave the smokes where they were permanently. Eventually, only a few months later, I did so. If what was left of my life brought stress, then I would live with it without an analgesic. I wanted to live. I was reasonably sure, of course, that I still had the choice.

Others, I had finally noticed, are not so lucky. After a lifetime of self-indulgence, I was at last beginning to be impressed by the possibility that abusing your own health might be an insult to those whose health has already been abused by the Man Upstairs, who really knows how to dish the abuse out the way it should impress you most – i.e. at random.

Our defence mechanisms against the anguish brought on by recognising the arbitrariness of the Almighty are closely akin, I suspect, to the defence mechanisms of the liberal intelligentsia in declining to recognise that evil might operate without a rational motive. As a member of the liberal intelligentsia myself (how could I not be? I went to Sydney University), I try to be alert to its weak points, and that’s one of them: we tend to believe that there is some natural state of justice to which political life would revert if only the conflicts between interest groups could be resolved. But whatever justice we enjoy arose from the conflicts between interest groups, and no such natural state of justice has ever existed. The only natural state is unjust: so unjust, and so savage, that we would rather not imagine it, even when, especially when, we are young and strong. Hence the defence mechanisms. Restricting perception so as to free us for action, they liberate us, but they are limiting, and sooner or later we have to examine the limitations, or the liberation will defeat itself. Facing reality ought to be an aim in life. It hardly ever is, and the pursuit of happiness can practically be defined as the avoidance of any such thing. But an aim in life it certainly ought to be. Just as long as somebody else does it.

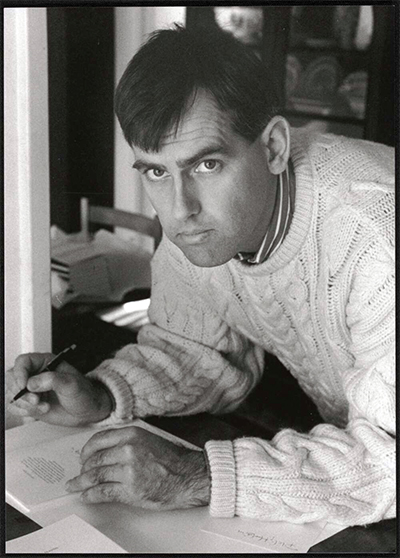

Portrait of Philip Hodgins, 1993, Bolton, Alex T. (1926-96), gelatin silver photograph, 17.7 x 12.7cm, Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an14466001-1, National Library of Australia

Philip Hodgins (1959–95) faced life. He would have been the first to say that he faced it only because he was forced to, but he did it. He faced life when he faced death. For him, death lit life up. In his final time on earth, he would sometimes deny this, but only in poems that lit life up like nobody else’s. Lavishly talented, he would have been a major poet whatever the circumstances. If he had lived as long as his admired Goethe, he would probably have been Goethe. Hodgins might never have written Faust, but he almost certainly would have produced a vast body of work in which art and science interpenetrated each other as if all the modes of human knowledge came from the same impulse: the synthesis that Goethe was so keen on. That kind of scope needs an inexhaustible knack for putting things in an arresting manner to go with the comprehensive intensity of perception, and Hodgins had that compound gift.

Looking at it from the other direction, his circumstances would have made him emblematic whatever his talent. Put the two things together, however – the talent and the tragedy – and you’ve got something with a force of gravity strong enough to feel on your face. It’s important to go on saying that, because his books look so slight. But they only look it. They weigh as if the language in them had been refined from pitchblende. Barely there between the finger and the thumb, when opened they put you into the world of physics whose heavy metals produced the rays that bombarded him in his illness. In his last book, sardonically called Things Happen (1995), one of his last poems quotes Goethe in its title. The dying Goethe is said to have called for ‘Mehr Licht, Mehr Licht.’ Hodgins’s title is a translation: ‘More Light, More light.’ Let me quote the first stanza. Usually, when a lecturer says ‘let me’, he means he’s going to do it anyway, but, for some of what Hodgins wrote as he grappled, whether early or late, with the looming fact of his awful finale, I do feel I need your permission. I’m going to assume it, and use it as a blank cheque. When this is over, you can decide whether I’ve abused your trust. But enough of the pleasantries. There’s no avoiding that first stanza any further. Here it comes:

Sickly sunlight through the closed curtains

that are white but much thicker than a sheet.

Sunlight with all the life taken out of it,

diminished but still there, an afterglow,

like the presence of a friend who has died.

You’re lying still and yet you’re moving fast.

Notice that, by using the impersonal ‘you’, he shuts out the ‘you’ that you would use for yourself. You yourself are just reading, not even visiting. You are well. You might have seen a friend die, but you have a life you’ll be going back to. Back out there in your life, the sunlight won’t have all the life taken out of it. It will be ordinary, everyday sunlight. You’ll be in it again – not in here. But then, with the opening of the second stanza, it turns out that you might be staying. By now he has made that standard device, the impersonal ‘you’ that should mean only him, into a personal identification that includes the person he addresses. You are not excused after all.

A nurse comes in to give the drip a shot.

He opens the curtains in a moment of revelation.

The sunlight is revitalised into an opportunist

and instantly takes over the room like a brilliant virus,

filling out even the places you had never thought to look.

Your life is changed. The room is shown to you as it is,

not as it dimly appeared to you all that time ago.

You’re moving fast and yet you’re going nowhere.

And that’s the whole poem. Critics shouldn’t quote poems whole, I think. When they do, they turn themselves into anthologists. But we need to see this poem whole because otherwise we might miss the shift from the lifeless light that floods the first stanza to the brilliant, viral light that scorches the second, the light that turns out to be even more lifeless, the death light, like the white light Ivan Ilyich sees in Tolstoy’s valedictory story, the dreadful story that tries to pretend Natasha Rostova never danced and Anna Karenina never loved. Seeing that shift of intensity, we can see the grim relationship between the poem and its title. When Goethe called for ‘More light’, he’d already had his share, and more than his share. He’d had enough of everything to get sick of it, which is not at all the same thing as being sick in advance. He’d had enough of fame and celebrity, for instance; enough to arrive at the accurate judgment that they don’t add up to much. But it’s still a lot more comfortable to arrive voluntarily at that conclusion after you’ve had them than to be forced to it before.

Goethe was dying of old age, which is another way of saying dying of life. What he wanted was more of what he’d spent three quarters of a century enjoying and describing. He just didn’t want to leave. He could scarcely complain of never having arrived. Hodgins could. Hodgins was dying with most of his life unlived. Hodgins was dying of death. As it happened, the prognosis he had received when he was twenty-four, that he would live only three more years, was short by almost a decade. But when the end finally came, he had still seen far too little of the light that left Goethe shouting for more after having bathed in it for a long lifetime. So behind the light that Hodgins makes so terrible in its truthful clarity, there is the ordinary light of life that he had seen too little of.

Most of the poems in the last section of Things Happen – the section is called ‘Urban’, and we can safely take it that every poem in it was written when he already knew he was a goner for sure – are, like ‘More Light, More Light’, terrible with the presence of the hospital’s fluorescent illumination and the hum of the sad machines. I could quote details for an hour. I could quote them until you prayed for release. That was exactly what he was doing, and the words prove it: ‘I watch the needle hovering over me. / It’s big. It goes in slowly and it hurts.’ That’s from ‘Blood Connexions’. Even without reading the whole poem, you can see that the sexual connotations might be fully meant, thus to complete the work of turning the world upside down. Or try this, from ‘Cytotoxic Rigor’: ‘You vomit through surges of nausea and pain. / And when there’s nothing left to vomit you vomit again.’

But here the critic, for once, ought to be an anthologist, because quoting fragments is unfair on both poet and audience. To quote fragments makes for a clumsily edited showreel of horror, when in fact every poem is a complete film, and even when possessed by death is still full of life. The needle in ‘Blood Connexions’, for example, is wielded by a female nurse, with whom the narrator really does have a kind of blood connection, because both she and he had their origins in the same country, Ireland:

The nurse unpacks a needle and a line.

‘We’re probably related,’ she almost jokes,

but wary of which side I’m on she looks

me in the eye, just momentarily,

a look that asks, ‘Are your folks killing mine?’

One need hardly note that the poem’s conventions of a romantic meeting are gruesomely transformed by the tools of intimacy. That’s where the poem started: the dislocation was the inspiration. The nurse ‘Undoes my catheter, makes a new connexion / And pushes in the calming drug’. But it is still a romance. It is still a determination to see the multiplicity of life, a refusal to withdraw into what would have been a very excusable solipsism, into a world bounded by the walls of a pillow when our head sinks into it. One or two of the poems in the last section don’t mention his situation at all. There are postcard memories of his last trip abroad, to Venice. He is remembering, but if we assume that he is remembering with bitter regret, it can only be an assumption. There is no bitterness on the page. The poems read as if he were remembering his first delighted response. Browning arrived in Florence with no more joy than this:

A vaporetto ducked across in front,

taking the same date and same short route

that Doges took for centuries

on their way to hear the multi-choral choirs,

while a pair of gondolas, as dark as submarines,

headed down the Grand Canal,

their prows curved up like the toes of slippers

in a Hollywood oriental musical.

Eugenio Montale’s gondolas slid in a dazzle of tar and poppies. Hodgins’s gondolas are less carefree, but they still dance. I can tell you want more of those gondolas. You shall have them, because he wanted more of them, too. He was sick, he knew he was sick, but he was so hungry to look, and to register what he saw:

Below our window to the left

about a dozen more of them

were swaying in between thin crooked poles,

neatly unattended and exposed,

reminding me how some religions in the east

expect that people entering a shrine

should leave their shoes outside,

as a mark of their respect.

From that, you would think he was going to live forever; or, anyway, you would think he thought so. And in fact we can stay in the same book, and merely go back a bit beyond the final section, to find magnificent poems that either fail to mention his fatal disease or else, even more remarkably, mention it as if he hadn’t got it. A startling example on this point is ‘A House in the Country’, one of the boldest things he ever did, a poem that puts a house into world literature the way Pushkin did when he described the lights going out in the soul of Lensky. At the risk of rampant intertextuality, I’ll quote the stanza presaging his final use of a further quotation that we now know he would forever make his own. But notice also what the stanza does not presage. Notice the effect that it could have employed but didn’t. When we notice that, it will lead us to the most amazing thing about him. It has already been established, before this stanza unfolds, that the house is riddled by a subversive presence:

I gazed at this miniature apocalypse

Of countless termites writhing in exposure,

No doubt programmed to crave the opposite

of Goethe, who had cried ‘More light! More light!’

and as the seconds dropped away as small

and uniform as termites a feeling burrowed

into me as bad as if I had cancer.

One ‘as’ after another, linked like a little chain of worry beads. How can he, of all people, be so definite about being indefinite? As if I had cancer. Well, we can be reasonably sure that the house has it. In the last line of the poem, the narrator is worried that for the house there might be no cure: ‘I set off at a fast walk, worried about / what was going on underneath my feet.’ The house has it, but an intergalactic literary critic who stepped off a spaceship could be excused for deducing that the poet himself does not have it, or he would have written a different way.

The intergalactic critic, however, would be deducing the wrong thing. At one stage, I was myself the intergalactic critic, and I can remember all too well how, with regard to Hodgins’s career as a poet, I got things exactly backwards. Stuck in my study in London, a long way from the Australian poetic action, I first noticed him in a little poem about a dam in the country. The poem popped up somewhere in the international poetic world: the New Yorker or some anthology. (If you’re serious about poetry, it’s probably the best way of finding out what’s really going on: when a poem hits you between the eyes, even though you don’t know anything about the person who wrote it, the chances are better that the person in question is the genuine article.) The rim of the dam featured a pair of ibises – ‘Two ibises stand on the rim like taps’. Immediately, I reached the correct conclusion that Philip Hodgins had the talent to write anything. It was the only correct conclusion I was to reach for some time.

By the time I read about Hodgins at length, in an essay by Les Murray now included in A Working Forest, Hodgins was nearing death. When I started to read Hodgins himself at length, I started in the middle and somehow convinced myself that his illness had snuck up on him, and had become a subject only towards the end, when he became aware of the threat. This was a conclusion easily reached from the seemingly untroubled richness of his central work. But it was the wrong conclusion in the biggest possible way. For a student of literature, the advantage of living abroad is that he is less likely to have his judgment pre-empted by gossip. The disadvantage is that there is always some gossip he ought to hear. Knowing about Hodgins’s possible death sentence earlier wouldn’t have altered my estimation of his qualities, but it would have drastically affected my appreciation of the way he brought them into action. Hodgins had known about his condition right from the beginning of his career as a poet. He had known that some periods of remission were the most he could hope for. That he had not made this his principal subject, or anyway the ostensible centreline of his viewpoint, was an act of choice. This act of choice, I believe, must be called heroic, but, before we call it that, we should look at some of the results, as they are manifested in what he left behind at the start, and then in what he passed through before he returned to what he left behind, in a curving journey which contains a world.

His first volume, Blood and Bone (1986), contained not only ‘The Dam’, which I had seen in isolation, but a cluster of poems less contemplative. In the long run, the dam and its tap-like ibises, with their effect of an Egyptian fresco discovered by flashlight, would set the poised tone for his central pastoralism. But in the first volume, they were as uncharacteristic as an embrace in the middle of a battle. Most of the first poems were anguished reactions to the news the doctors had given him: news about his blood; news that gave him a new measure of time. The last three of the five tiny stanzas that make up the poem ‘Room 1 Ward 10 West 23/11/83’ give us a summary:

I am attached

to a dark

bag of blood

leaking near me

I have time

to choose the words

I am

likely to need

At twenty-four

there are many words

and this one

death

Though Hodgins probably did not mean us to, it is impossible for us not to think of the girl who gave her age in disbelief to the German engineer at Babi Yar as she was driven naked towards the pit. What is happening here is a wartime atrocity. Wartime atrocities happen in peacetime. Chance behaves like a homicidal maniac. It is one of Hodgins’s messages, and it could have been his only message for the rest of his short career. He had the power of language to make it stick. His first book is full of moments like that. In ‘Ontology’ – a resonant title for someone whose existence has just been put into question – he collapses, or seems to collapse, into an inconsolable solipsism:

... The universe

is going cold, there is no God,

and thoughts of death have taken root

in my intensifying bones.

He knows this is self-pity. He calls it that. He called a poem that, ‘Self-pity’, and put into it the pure expression of a purely personal emotion, thereby letting the rest of us taste its tears, if we dare to.

But happiness has been serendipity.

It happened in the ambulance on the way back

from centrifuge. I sat up like a child

and smiled at dying young, at all

love’s awfulness.

In the first line of ‘The Cause of Death’, a deadly wit got into his range of effects. ‘Suddenly I am waiting for slow death.’ Like the sudden sitting up and childish smile, the wit was a hint that he would find a kind of liberation in this prison. (Though Rilke was always pretty careful to keep his living conditions as comfortable as possible, the liberating prison was an idea he was fond of, so it is not strange that Hodgins was fond of Rilke, and cited him often.) But first Hodgins had to conjure the prison’s stone walls and iron bars, and he went on doing it over and over. In ‘Trip Cancelled’ (and between the title and the first stanza, we have already guessed why the trip was cancelled), he says: ‘The words for death are all too clear. / I write the poem dumb with fear.’ How could he write the poem at all? And how could the poems be different from each other? In ‘From County Down’, he seemed to wonder that himself.

My bad luck is to write the same poem every time.

A sort of postcard poem

from the rookery. Timor mortis conturbat me.

I never wanted this.

We can be sure of that. But we can equally be sure that he’d seen a possibility. We might not have done, and this time by ‘we’ I mean I. To the extent that I know myself, I’m fairly sure that I would have given up. But Hodgins seems already to have had an inkling that he might have been handed a way back to his deepest memories if only he could keep concentrating.

There are hints of this awareness even in ‘Question Time’, a poem that takes it for granted the clock will soon stop: Noone can say when. / It’s a bit like flying standby.’ But there’s the wit already, and, at the end of the same poem, the hope that persists on surfacing through despair: the hope that something might be achieved even now:

What you knew began with wonder

on your father’s farm

and though it wouldn’t be that good again

you could have gone on so easily.

He never went on easily, but he did go on, into the great central period of his achievement that we can already see as one of the glories of late twentieth-century Australian poetry. To a large extent generated by the rise of Australia to the position of an interconnected communications metropolis, a component of the global artistic hypermarket, one of the most remarkable multiple creative outbursts of modern times had the poetry of Philip Hodgins as part of its central cluster of events, and his poetry was much more pastoral than urban: it almost always had something to do with the farm. It was about a vanishing world, and it was written by a vanishing man. But in both cases, he found a way to keep the loss. One death poem, ‘Walking Through the Crop’, starts like a renunciation:

It doesn’t matter any more

the way the wheat is shivering

on such a beautiful hot day

late in the afternoon, in Spring.

But it does matter, or he wouldn’t be saying so. It’s the writerly paradox that lies at the base of all poetry about despair, and in that paradox the young Hodgins has just received the most intense possible education. The death poems went on into his second volume, brilliantly called Down the Lake with Half a Chook (1988): I say ‘brilliantly’ because there could have been no more economical commitment to the Vernacular Republic than to give a book of verse a title so echt Australian that it would need to be translated even into English. ‘The Drip’ is the most terrible of all the needle poems. It registers what happens when the needle comes out at night – damage to the damage:

The tape and gauze

across my inside arm

are lying there like dirty clouds,

and what is underneath

is like a gorgeous sunrise.

This is beauty as dearly bought as it can get. It would have been no surprise if Hodgins had stuck to these themes until the end, no matter how long the end might have been postponed by remissions. Most artists don’t know what a winning streak is when they are on it. A few know how to follow where it leads, and only a very few, the great ones, knowing exactly what it is, get out early and look for something else. Somewhere about the time that his projected three years were up and he found himself still alive, Hodgins expanded his range into the unexpected, and began talking as if his memories of his upbringing on the farms were going to accompany him into his old age. He knew they couldn’t, but he talked as if they would. ‘A Farm in the High Country’ is typical of his poems in this manner: typical, that is, in being pretty much a masterpiece:

And it was easy not to notice that black snake

sunning itself on top of some worn-out tyres

until it melted off quickly like boiling rubber

and flowed through a stretch of dry grass

with the sound of the grass beginning to burn

From here until his final phase in hospital, you just have to get used to being astonished. Les Murray, himself the convener and consolidator of the post-World War II movement that surrounded Australian poetry with the vocabulary of the working land, as opposed to using the land for a mere backdrop, was clearly right to salute Hodgins as a pastoral poet without equal. The only way to evoke what Hodgins did would be to invoke it all: to become such an anthologist that one would quote almost the whole of the central hundred pages of New Selected Poems (1997), which would include nearly everything in the twin touchstone single volumes of Hodgins’s main manner, the booklets called Animal Warmth (1990) and Up On All Fours (1993). There is poetry here in such abundance and intensity that the word ‘great’ is not out of place: in fact, it refuses to be excluded. Moments of incandescent registration are so stellar in their profusion that he gives the impression of having held constellations in his hands.

Clive James

Some limiting statements can be made, and if they can they should: Hodgins himself, after all, had no love for dreamland. When Hodgins rhymed solidly, he gained from it. But he seems to have found solid rhyming meretriciously neat. Deciding that, he should have avoided near-rhymes. They draw too much attention to their rattling fit even in song lyrics, and, on the page, in poems, they hurt the eye along with the ear. With reference to the longest of his longer poems, the verse novel presents difficulties that make titanic demands on the poet. Murray set the fashion for the form with The Boys Who Stole the Funeral, and brought it to a peak with Fredy Neptune. He made it an Australian form, in fact: by now it is part of our literary landscape. But no amount of tactical diversion can disguise the fact that in a verse novel the characters are all saturated with the poet’s mental acuity, and so all end up thinking like him, no matter how unsophisticated they are made to sound.

Hodgins’s verse novel, Dispossessed (1994), was written at about the same time as Fredy Neptune, but was nothing like as developed in its internal action. As much as all the others of Hodgins’s rural poems put together, Dispossessed concentrates attention on the physical existence of the rural life that is on its way out of the world. But nothing can stop all the characters turning into poets, simply because there is so much poetic perception going on around them. Nor does the blank verse do enough to mark the local outbreaks of poetry as parts of a single poem. The book would work just as well, just as poetically, if it were prose, and I seriously suggest that somebody one day might take the dare and print it that way.

More heretically still, let me suggest that Hodgins’s terza rima mini-epic, ‘The Way Things Were’, one of the two big showpieces of his first great central collection Animal Warmth, suffers the same fate as Louis MacNeice’s Autumn Sequel. Marvellous though it is in its remembered observations, ‘The Way Things Were’ drags its feet – as, indeed, does its companion piece, ‘Second Thoughts on the Georgics’ which, like Dispossessed, is cast in a blank verse all too blank. But ‘Second Thoughts on the Georgics’, whose poet can be commended for getting his hands far dirtier than Virgil ever did, merely makes too much of getting along: it doesn’t irritate while doing so. ‘The Way Things Were’, I am afraid, does. Even MacNeice, the supreme verse technician, gave up on the idea of sustaining the terza rima in English with solid rhymes. But instead of reverting to the dextrously mixed and switched classical metres of its masterly predecessor Autumn Journal, he pushed on with the terza rima just to be different, and used half-rhymes just to sustain it. The result, Autumn Sequel, seems like a structure only to the eye, and Hodgins’s rhymes in his terza rima piece have the same fault compounded, because they are even more loose than MacNeice’s. Often a single consonant is the only thing that a triad of rhyming words have in common. I was quite a way into the poem before I realised that a gesture was being made at the terza rima. I thought he wasn’t rhyming at all.

And in that case, it would have been better if he hadn’t. The truth was that he hardly needed to. Most poets lose out when they abandon overt form, but Hodgins was one of the lucky few that gain. His ear was so sound that he could develop a seductively articulated texture of echo over any group of unrhymed lines. His villanelles and other systematically repetitive forms got in the road of this quality, and suggested that their main value was to help the poem get done. Flatness in Hodgins would not be so obvious if his peaks weren’t so numerous: put in geographical terms, his main output would look like one of those Chinese landscape paintings in which the multiple upsurge of pointed mountains looks too extravagant to believe, until someone who has been there tells you it’s all true. Anything in Hodgins that sounds willed, or manufactured to a template, is competing with poems like ‘The Rabbit Trap’. But the only poems like ‘The Rabbit Trap’ are his. ‘The Rabbit Trap’ comes from heaven. Listen to how the last stanza starts in wit and proceeds through a Montaigne-like detached sadness into a sadness no more detached than that of St Francis of Assisi:

So sensitive and yet it is unfeeling,

always reacting badly to slightest

pressure on the blood-stained centre plate,

the stage where little tragedies are played out

while back in some warm spot the mother’s young

stare out as the world closes in on them.

Almost demanding to go unnoticed in the middle of that sumptuous progression is the linking of the trap’s centre plate to a theatrical stage. Pause for a moment and you will see the trap’s laid-out surrounding jaws as an auditorium. But he moves you to the next moment. Giving you more than you can dwell on at the time is one of the ways that the master poet declares himself. But I could quote from Animal Warmth and Up On All Fours until the cows come home. I could quote until the cows came home about the cows not coming home. In the Australian countryside according to Hodgins, every brutal thing that can happen to an animal happens on the page.

Clearly, most of this uncooked vividness was remembered from childhood, but in his mature years, with the needle of nemesis always at the edge of his vision, he reinforced his memories with plenty of hands-on experience. As his football poems remind us, his illness didn’t stop him being intensely physical: or anyway, that’s the way he makes it sound. In the poems, he stabs pigs, despatches wounded rabbits, watches the calf being born from an inch away. He watches afterbirth being eaten and practically gives you a taste. Except for the squeal of the boiling yabby (there is a PhD to be written about the role of the yabby in the poetry of Philip Hodgins, so let’s hope nobody ever writes it), nothing turns his stomach. Brutality is the price of authenticity. The price of country produce that tastes of something is that an inescapable violence occurs behind it. There is violence even in the milk: ‘The sweetest milk / was lucerne in the spring.’ But if the cows eat the wrong stuff, they bloat, and they don’t come home:

It’s always a blow to lose a cow that way –

squeezed to death from the inside,

hugely round with legs jutting everywhere

like some washed-up unexploded mine.

Those lines are from ‘Second Thoughts on the Georgics’, which, I just finished saying, made slow progress in its narrative drive. So it does, but one of the reasons is that it is packed with observations as good as that. The reader has to deal with almost a monotony of quality. In Hodgins’s poetry about the land, you must get used to the way he brings everything out in high relief, a democracy of vividness as if the truth-telling particularity of a painter like, say, Menzel had been carried out with the fantastic allure of the Douanier Rousseau. The narrator is always going where you don’t particularly want to look, and looking hard: into the guts of a rotting sheep, into the penile lustre of a rutting bull. Not even the quality of the expression can make most of this delightful. But it is made valuable. These are tougher laws than the ones we live by in the denatured urban world. The country is a world with its own rules, and the rules are severe: even the people can die like the animals. In one poem, a little boy disappears into a grain silo.

The question will always remain whether, when the little boy is sucked to his death amongst the nourishing grain, we are meant to think of the author, arbitrarily expunged in the midst of life. Was he thinking of himself? How could he not be? And yet surely the mark of his main poetry is that he is not asking for a biographical interpretation: that he is doing everything he can to avoid it. He is trying to say that real life, country life, is like this anyway; you don’t have to be fatally ill to find it unsentimental and ruthless; it has those characteristics by its nature, because it is close to nature.

This quarrel will go on. If I am afraid of anything in Hodgins’s future, it is that he might be as much debated over as enjoyed. But he won’t be more debated over than enjoyed, because there is too much to enjoy, and the enjoyment is too intense. It will be his immediate appeal that will lead to the annotated editions for future use in colleges across the English-speaking world. There will be footnotes to explain that ‘galvo’ was once Australian shorthand for galvanised iron, and the generation after next might need to be told that a ‘ute’ was the SUV of the past, when there were dirt roads. But Hodgins’s poetry will say what the dirt roads were, and how they sounded through the floor of the vehicle:

and there is the sound of a quarrel

beneath you.

Most of it is muffled and deep-throated

but there is also a top register

of small sharp stones

pinging off the metal as they shoot up.

You don’t get this variety with a sealed surface.

No, you don’t. On behalf of his country upbringing, Hodgins defied, as Les Murray did, the inexorable expansion of the sealed surface. There is a connection between agrarian conservatism and peeled-eyed poetic realism that can be traced through Prussia, the American south and Argentina all the way into recent times. A last-ditch stand by literati who know how to dig the ditch themselves, it has little to do with the traditional opposition of left and right. Agrarian poets, indeed, are likely to find an even bigger enemy on the right than on the left, because it is the capitalist imperative of industrial efficiency that denatures the country. And it does, after all, make life in the country more bearable for the few who remain to work their land. Most of the inventions that brought the efficiency about were devised by their forefathers, who, even when not yet dispossessed by the global reach of improvement, were already worn to a frazzle by the rigours of the life and wanted something better for their children. (One of the reasons I would like to see Dispossessed restored to the status of a current book is that it so bravely tells the sad truth about how a losing battle can breed narrow minds.) Something better came, but it was more bland. When everybody has enough to eat, hardly anybody cares any more about how the food gets to the table. The salt loseth its savour. Wherewith shall it be salted? From an historic dilemma comes an artistic question. It is an historic force that Hodgins’s sort of poetry braces itself against.

Hence, perhaps, some of the poetic strength. But in his case, the fighting courage goes immeasurably deeper, and it is at this point that I must switch into that comfortable mode of peroration by which I get the centre of attention away from him and back to me. Hodgins’s courage I can’t measure or even identify. All I can do is comfort myself that it was only one of the factors in the recognition that came to him before his death. If valour, whether moral or physical – and his, of course, was both – were the sole criterion for recognition, most of us would have to give up on the idea, and stick with what celebrity we can get. I hasten to add that I haven’t quite given up on celebrity, either. It can help. Perhaps I would have had a lot more trouble getting my poems published if I had not had my face on television. It always seemed to me that it scarcely helped at all, but I might have thought that because, with being published as with being in love, rejection is more memorable than acceptance.

It isn’t always to the worthless that celebrity draws attention. The world of mass enthusiasm is much more like a pure market than like a public relations campaign. In Britain, a touchingly under-qualified creature called Posh Spice has defied our expectations by remaining married to the footballer David Beckham for all these months, but she hasn’t defied the law of supply and demand: she will always sell more newspapers than records, because the public, although it will read anything about a permanently pouting young woman with delusions of adequacy, refuses to be fooled about the music it listens to. Completely to manage the public’s taste is an ambition open only to totalitarian societies, not to free ones, and in fact not even classical communism could manage it: the Beatles still broke through. There was something I might have said about Madonna earlier on that I must say now, merely to be just: she once really got the youngsters excited, and might even have done some good. A friend recently sent me a collection of French songs sung by Carla Bruni, who is apparently celebrated for being the sort of well-connected and well-constructed young supermodel that Mick Jagger spends hours on the treadmill in order to pursue successfully. Well, good luck to him, because he would certainly be right in her case. She sings beautiful songs beautifully. If she hadn’t first been a celebrity, I might never have recognised that, so the two things are bound together.

Most of the more off-putting aspects of the abundant West arise from its freedoms. The first thing we can be sure of about a free society is that it will be teeming and throbbing with things we don’t like. We live in Luna Park, not Plato’s Republic, and artists should be grateful that they have been given such variety to be creative about. There have been, and always will be, plenty of despots ready to give them a lot less. So welcome to the crazy house. But it does become more and more apparent that we will have to reinforce the foundations even as the edifice shakes with the urgent vigour of its productivity. It might be as difficult as getting new reinforcing rods into concrete that is being squeezed from within by the expansive oxidisation of the old ones. Recognition is just such a reinforcing rod. Unequivocally, recognition is a proper aim in life. But just because it is so obviously worthy, there is no reason to think the young won’t get the point. Already they find it cool to know the name that everybody else doesn’t know, and there would be no credibility in that unless the unknown names were good for something, even if only for an even more unintelligible version of gangsta rap.

What I did to get the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal – this outstanding emblem of recognition in a country that has so spontaneously developed an outstanding literature – never made me famous while I was doing it. As a poet, I spent two thirds of my career without even a reputation. Receiving this award, I feel like someone who has run the whole race invisible and popped into sight at the finishing line. Well, that fits. To be recognised means to be reassured that you were right to pursue a course that had no immediate rewards, and got in the road of activities that had. Poetry is something I gave at least part of my life to: a fact on which I often preened myself, at least in private. Now, to remind me that I had things easy, I have been honoured in the name of a man who gave his whole life to it, and his death as well. So the honour seems disproportionate; but I suppose an honour ought to. When a Roman general, returning from his conquests abroad, was awarded a triumph, a special herald rode in the chariot with him through the cheering city to whisper in his ear and remind him that he was made of dust and shadows. The occasional general no doubt said: ‘Bugger off, I’ve had this coming for years.’ At least with this triumph, with a name like Philip Hodgins on the laurel wreath, no recipient is in danger of saying that.

In July 2003 Clive James attended the Mildura Writers’ Festival, where he delivered the 2003 La Trobe University/Australian Book Review Annual Lecture and received the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal.