- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Paradox of Jazz

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

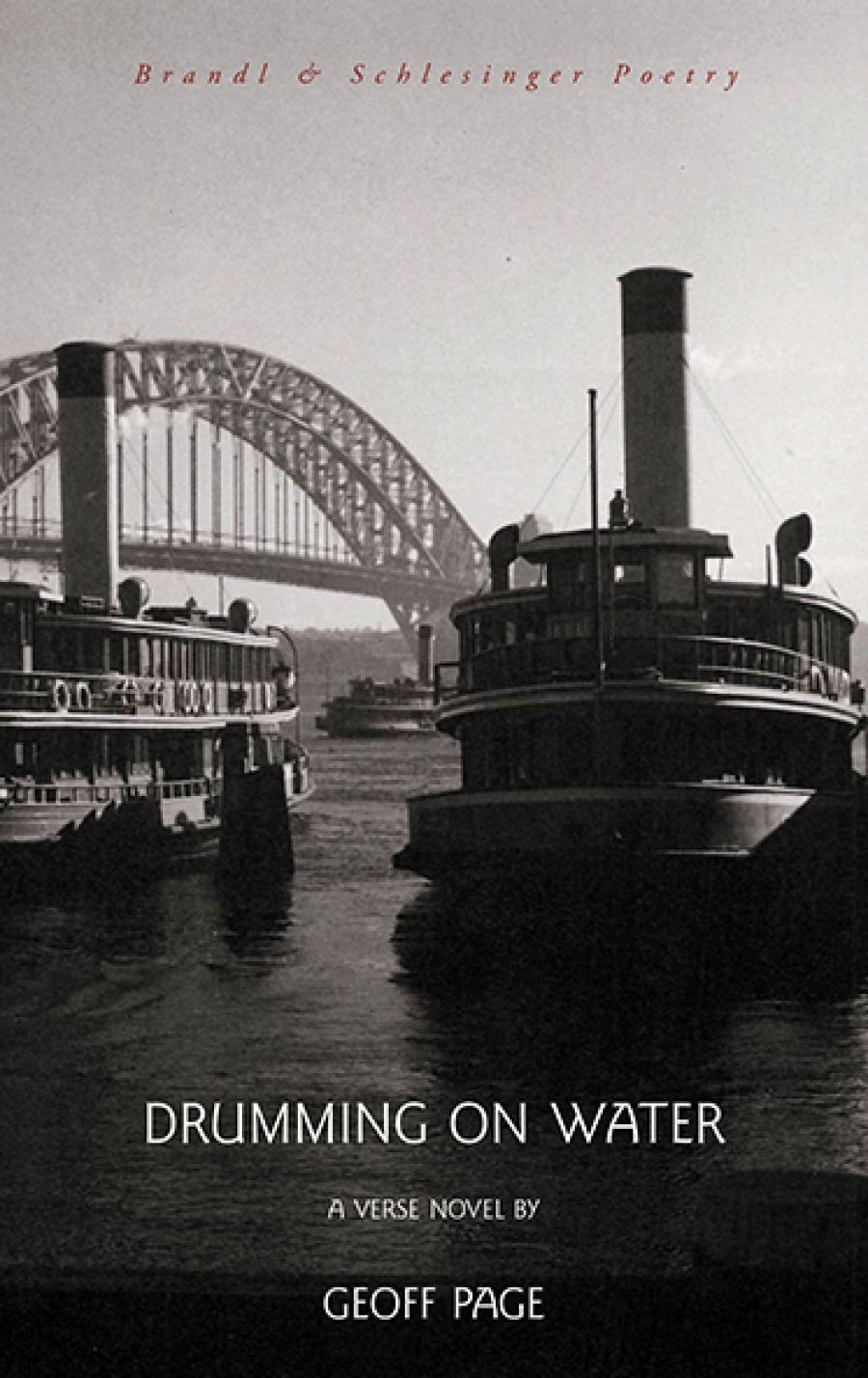

Like a series of attenuated conversation poems, Drumming on Water is a narrative in forty-five riffs. The individual poems are like extended song lyrics – spoken jazz: ‘ad lib, of course / but also well thought out.’ The words are notes to sound and repeat, scoring the brief and unmemorable career of a jazz drummer with the Lizzie Rivers’ All-Girl Band of 1938 and regular gigs on Sydney Harbour ferries, until the mysterious death of its lead singer who disappears overboard – the fulcrum of the poem.

It’s hard to overstate the sophistication of the poetry in this new verse novel (though verse narrative or novella would be more accurate). Drumming on Water sets a new benchmark in Australian poetry: smooth, elegant, vernacular and deceptively complex. It is an engaging read.

- Book 1 Title: Drumming on Water

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $26.95pb, 116pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Drumming on Water is not tragedy or epic or terror (gothic or otherwise) on a grand scale, though there is a possible murder/mystery which, like Emily Potter’s claim for Chloe Hooper’s A Child’s Book of True Crime at the recent ASAL conference, could offer itself as a metonym for a larger cultural crime: the entrapment of talented women. The emotion is recollected, but not necessarily in tranquillity – there is anger, pathos, spite and brooding uncertainty, as well as flip irreverence. Page is a poet of the middle ground: sceptical, existentialist, agnostic, an interrogator of popular culture and the human psyche.

This reaching back in time to interrogate history and retell stories (re-examine the news, reassess folklore) reminds me of Charles Harpur’s ‘The Creek of the Four Graves’ (1853), as well as Slessor’s two ‘Five’ poems, and Dorothy Porter’s Akhenaten (1992) and What a Piece of Work (1999). These poems claim the imaginative spaces of language to play with events, voices, fragments of documents and invented dialogue, though Page rejects Porter’s passionate intensity, as he does Alan Wearne’s documentary loquaciousness for a sparer, sinewy conversational immediacy.

Like his previous, haunting verse novel The Scarring (1999), Drumming on Water is set against a backdrop of World War II. Indeed, there are some interesting links, such as when the band’s manager, Sam Dillon (sleaze, possible villain, but ultimately human and mortal), is sent to New Guinea with Australian Army forces, having been reclassified under the Manpower legislation. His death recalls ‘Beach Burial’: ‘floating weightless in / the gutted hull of half a ship.’

The title is significant because it points to the narrator’s role in the all-woman band and indicates the contemporary social, historical and musical context of the poetry. It suggests an image of the futility of human and artistic effort, and seems like an attempt to exorcise or conjure the ghost of ‘Five Bells’, which haunts this poem: ‘But all I felt was lack of air.’ Drumming on Water is a gendered elegy, an imaginative tribute to a female Joe Lynch. Part of the restless insistence of the poem is the gnawing attempt to find logic in the death or in its aftermath that will explain (and justify) the lives of the central character and the narrator. The Harbour, the lack of a body, the incompleteness of a rational or divine framing of the universe redefine Slessor’s sense of settling for all there is – teasing moments arrested ‘in the moon’s drench’ or at the back of a hundred yachts.

The brief life and mysterious death of the lead singer – ‘Lizzie Rivers, risky singer, / nightmare of the nuns’, rebelling against the constrictions of her upbringing and family, and also against the pressures and power exercised over her by men – provides a lens for the narrator to examine both the Zeitgeist and her own life. Lizzie, privileged and glamorous, is an upper-class, good-time girl. She is both a role model and nemesis for Emma who never entirely fails to conceal her grudging attitude to rich girls.

Emma Patching, the drummer-narrator, is talented, but her voice is mundane, and she settles easily for the trappings of marriage, children and suburban values of Sydney in the 1930s. She is a good girl who will only practise sex safely, and with the one man, after marriage is well in sight. As such, hers is an ideal vantage point from which Geoff Page can epitomise the times, like a chorus with a conscience.

Behind the poem is Page’s interest in jazz, so it’s not surprising to find the poetry suffused with the raw, mournful tones of Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday, plus the Sydney Trocadero scene of the mid-1930s, with Benny Goodman and Showboat in the offing. There’s a newsreel sense of Sydney from Bowral to Balmain, Paddington to Vaucluse.

Drumming on Water is also focused on the language and the process of the telling, as well as on what is told. It is interested in where art and historiography begin. Drumming proposes about five different and inadequate causes or explanations for its ‘story’, as the narrator ponders its significance.

Many of Page’s poems are focused on war or the memorialising of history. In the justly celebrated ‘Smalltown Memorials’, Page writes poetry dealing with documentation, as he explores the place of individual lives in the records of public history. Remember, too, his ‘Belanglo’, which concerned the familiar anonymity of the life of the infamous ‘backpacker murderer’. Page has a forensic interest in how and why things happen, why people do things, without succumbing to the sensationalist rhetoric of detective fictions.

Whereas Patrick White said of his own work that he was interested in the ‘extraordinary behind the ordinary, the mystery and poetry that make [lives] bearable’, Page’s work rejects a metaphysical grandstanding, finding the ordinary within the extraordinary, the grounded, messy complexity that is so often ‘transfigured’ and evaded in art. In Drumming on Water, Page is reclaiming the forgotten stories behind the historical record. This verse novel utters words that have been silenced and reimagines them, as whispers of another possible history – ‘the paradox of jazz’.

Comments powered by CComment