- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

You have to sympathise with Nikki Gemmell. When she described her sense of liberation on deciding to publish The Bride Stripped Bare anonymously, she seemed to have in mind only a desire not to offend people close to her. She would also have liberated herself from the literary celebrity machine. But, once the game was up, she got even more of it than she would otherwise have done. It doesn’t seem to have bothered her too much. The profile in The Age and the appearance on Andrew Denton’s television show didn’t suggest that she was determined to salvage what she could from her original plan to stay invisible. Some of my more cynical friends have suggested that that was what she had in mind all along. But the book is written with a candour that confirms her avowals.

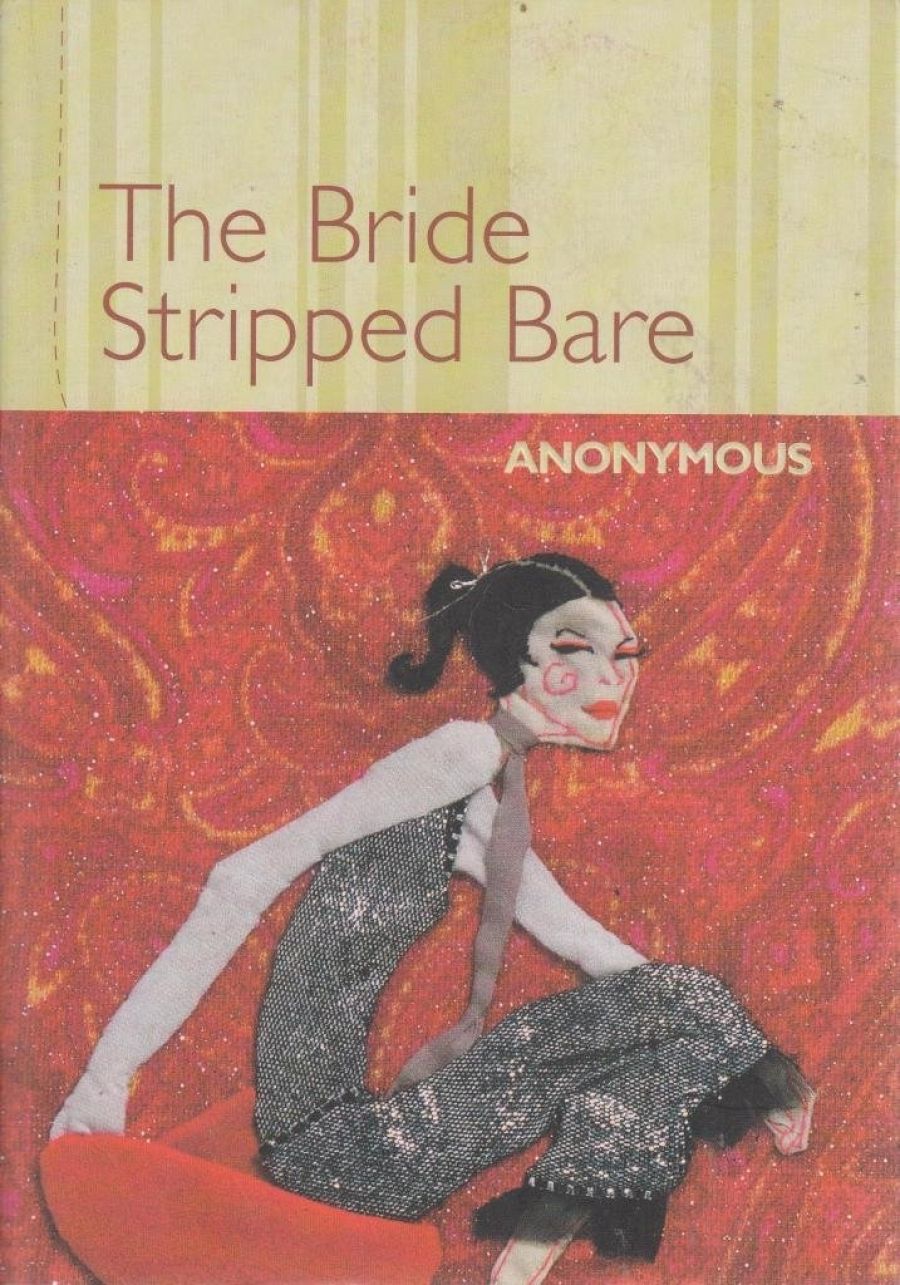

- Book 1 Title: The Bride Stripped Bare

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $24.95 pb, 376 pp

The Bride Stripped Bare is a hybrid book in some ways. Neither straight erotica nor psychological realism, it presents sex both in its fantastic, secretive aspect and in the larger web of social, emotional and familial ties. Scenes with a trio of taxi drivers notwithstanding, Catherine M. this is not. It is about the progression from ignorance to knowledge, and from constraint to a putative inner freedom.

Gemmell does a good job of keeping the fantasy element grounded in plausible details of everyday life. She uses framing effects like chapter headings from Victorian domestic manuals — the duty of girls is to be neat and tidy, nothing impure should be left in a bedroom one minute longer than necessary, that kind of thing. An introductory letter from the narrator’s mother noting the circumstances in which the manuscript was found. It is written in the second person, a second person which is perhaps a plural, just as the book as a whole is dedicated not just to ‘my husband’ but to ‘every husband’.

The Bride Stripped Bare is always readable and engaging. Although the Everywoman trappings threaten to depersonalise the main character and deprive her of dramatic force, the book makes a fine tradeoff between the specific and generic.

The book opens in Marrakech, where the unnamed narrator is honeymooning. Although she and her picture-restorer husband, Cole, have known each other since university, their affair began almost by accident when he turned up in Edinburgh looking for somewhere to crash. Their love, the narrator writes, ‘glows like a candle rather than glitters’: ‘It had taken you a long time to wake up to some sense. You used to sleep with men you were comfortable with to make yourself comfortable with them; you marry the one you forget yourself with.’ By now, sex is less important in the relationship; they are both somewhat inhibited.

Standing to one side of this relationship is the narrator’s best friend, Theo, a sex therapist who has a white marriage with a bisexual man twenty years her senior. Theo knows everything about sex but is not on especially good terms with it in her own life. Theo has all the impulsiveness and eccentricity the narrator lacks: their friendship follows the pattern it formed at school, where the narrator was the shy one and Theo was expelled for writing letters to the Pope about contraception. Towards the end of their honeymoon, the narrator comes back to the hotel room to hear her husband talking on the phone:

I can’t wait to get out of here, it’s driving me crazy, the heat, and he says this in his special voice, your voice, but there’s a playfulness, a lightness, it’s a tone you haven’t heard for so long. All she ever wants to do is run off to the markets and have rides in those fucking carts, I can’t stand it, I get so bored, I just want to relax. He pauses. Diz, Diz, no, you can’t. He chuckles. Yeah, me too. I’ll see you soon, thank god.

Cole is talking to Theo. He dismisses her accusations but, unsurprisingly, she is not convinced. Alienated from her husband and from her best friend, the narrator’s mind starts to wander to the world outside the house. In a café, she meets a man slightly younger than herself, a semi-employed actor, Gabriel: he disappears and reappears later, at the London library where the bride has gone to research a seventeenth-century marriage handbook.

Although he is an actor and his father a bullfighter, Gabriel is not quite the untamable male of traditional erotic fantasy, the wild sexy dancing man who stands in opposition to the good provider. He is soft and receptive, entirely lacking in narcissism. He is also almost completely without sexual experience and, technically, a virgin. The bride commences to give him lessons.

A weekday afternoon. Once a week. Always Gabriel’s flat. You’re a good teacher, you always have been, and now after years of being the good teacher you don’t want to just give, you want something back. There’s one condition, you make it clear from the start: this arrangement must not, in any way intrude upon your regular life. It’s the only way you can make it work. When the lessons come to their end you will both disappear back into your worlds so that in the future, if you ever pass by chance on the street, you will not acknowledge each other or what you have done during these weekday afternoons in his flat.

But things don’t work out quite like that. The bride learns that there is a point to the dullness of home: it protects us from the beasts in the metropolitan jungle.

The narrative proper, however, ends on an upbeat note of contentment and resolution. But we already know from the mother’s introductory passage that the bride has effected a mystic escape from all bonds.

Comments powered by CComment