- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Rain of Dollars

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Early in the 2003 AFL season, Peter Rohde, the new coach of the Western Bulldogs, announced as one his initiatives that players should either find parttime work or some similar engagement consistent with their club commitments, or embark on a TAFE, university, VCE or other study programme. This mildly sensational proposition was designed to reduce the aimless hours spent by many players, especially the young and unencumbered, loitering in malls, coffee joints and other haunts.

Perhaps Rohde, whose fairly disastrous first coaching year belies his articulate and intelligent approach to the game, had in mind a problem more serious, less graspable, than simple time wasting. Perhaps he was observing that modern professional footballers risk becoming more and more disjoined from the people who come to see them play; that the upper echelon members of a homegrown and still highly parochial sport can easily become exotic, rarefied, a different breed; and that, worst of all, they might come to believe in their own fancied difference, a condition known at ground level as ‘believing your own bullshit’.

- Book 1 Title: Playing God

- Book 1 Subtitle: The rise and fall of Gary Ablett

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $29.95 pb, 343 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

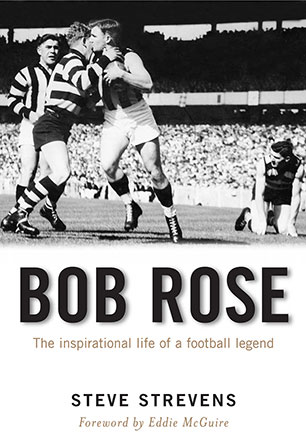

- Book 2 Title: Bob Rose

- Book 2 Subtitle: A dignified life

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 320 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Of course, all manner of élite athletes are vulnerable to this condition, but, on a bigger stage, the world stage, those who strut because they cannot dance are soon found out with a precision and bluntness often absent from the affairs of the parish, where local heroes tend to be protected from reality by the penumbra of fame, difference, privilege and awe in which they move.

When Ricky Nixon, agent for the disgraced Wayne Carey, approached Carey’s then estranged wife, Sally, in the hope of beginning some form of reconciliation, he was strenuously rebuffed. As Garry Linnell reports it, ‘“You’re to blame for this,” she told Nixon. “You’re to blame, the club’s to blame, I’m to blame … We’re all at fault. We never said no to him. We let him think he could get away with everything”.’ (My emphasis).

Likewise Gary Ablett: ‘Gary Ablett had been given more than the keys to a city; he owned Geelong and there was nothing anyone wouldn’t do for him,’ writes Linnell of Ablett in the immediate aftermath of his stunning performance in the 1989 grand final against Hawthorn. ‘By the start of the 1990s, the club would go to extraordinary lengths to protect their greatest asset; it had shielded and cosseted him from the rigours of everyday life ever since his arrival in 1984… ‘ (My emphasis).

It is something of an old story, though we tend to forget quickly. Tony Lockett was similarly protected and shielded: the difference was that his club, St Kilda, was no good at it and so moments of high protectiveness degenerated into ludicrous public performances, as when Lockett threw his crutches at photographers pursuing him into hospital. But the intent was the same, and its impact was similarly destructive.

‘Cosseting’, over-protection, shielding from everyday realities, are the common, though not inevitable, concomitants of a phenomenon that has been dear to Australians: the naturally brilliant, raw and naïve young fellow who emerges more or less unannounced from the bush and takes the city by storm. Don Bradman, Dougie Walters, Glenn McGrath, Tony Lockett are names that spring quickly to mind, and plenty of others can be drummed up with a bit of thought. This romantic figure has died hard in a rain of dollars and the circling spotlights, flashing cameras and spurious accolades of the celebrity culture. Some, like Bradman, handled the pressures; some, like Lockett, survived and eventually overcame them. Others, like Ablett, were destroyed by them. And then there was Bob Rose.

Bob Rose: A Dignified Life and Playing God: The Rise and Fall of Gary Ablett have, on the face of it, as little in common as their subjects. Rose grew up in Nyah West among Mallee farmers for whom life was mostly a struggle. As a boy, he planted his own vegetable garden and sold vegetables and rabbits around the district, carting his produce by bike. As a schoolboy, Rose did odd jobs and farm work, captained the school cricket and football teams and philosophically accepted his exasperated teacher’s proposition that ‘sport will never get you anywhere’.

Rose grew up among decent, hard-working, relatively narrow-thinking bush people in conditions that accelerated maturity and put a premium on responsibility and reliability.

It may be that Strevens’s description of life in Nyah West is a little over-wholesome, but it is nevertheless convincing and attractive, and, in any case, the Roses’ years of backbreaking work on the ever-present edge of financial disaster, effectively evoked by Strevens, easily balances any tendency to romanticise Rose’s early years. It is easy, in short, to understand why Rose became such a fine and exemplary human being. But there was one other ingredient, both enhancing and potentially complicating: his phenomenal sporting ability.

And that was the one thing he shared with Ablett. Their football careers were separated by decades. They played for very different clubs – Rose’s Collingwood tough, unforgiving but reverential of its awesome tradition; Ablett’s Geelon ‘small town’, ‘haunted by ghosts of the past’, riven with factions. They grew up in different bush environs – Rose’s Nyah West agriculturally marginal, remote; Ablett’s Drouin becoming during the 1970s ‘semi-rural’, gentrifying at one end of its social and architectural spectrum, and decidedly ragtag at the other. Ablett was well embarked on membership

of the latter when, like another Drouin boy, he was saved, at least for the moment, by his sporting skill. ‘Without boxing,’ Linnell says, ‘Lionel Rose might have become just another blackfella in Drouin, a man to steer clear of in the main street …Without football, Ablett might have been condemned to much the same future.’

Without football, Bob Rose would have done all right, but his extraordinary gifts allowed him to make his life a little easier, more interesting, more fulfilling. He was an unassuming champion at everything he did. He was, of course, one of the greatest footballers ever to pull on boots; he was a tough, scientific and successful boxer; he was a fine coach, a man who upheld and lived by the values of ‘good sportsmanship’, which, sensibly, did not preclude him from running straight through an opponent or deftly decking someone he considered in need of a fall. The times he played in ensured that his mettle was tested by only modest celebrity. A few bob a week from the club, a sling from John Wren, basic help with accommodation and a job – they were all-important, even at times

crucial, but scarcely corrupting and, even if they were, it is simply impossible to imagine Rose succumbing to fame in the way that Ablett did. Steve Strevens doesn’t urge this view on us, nor does he make the mistake of suggesting or implying that Rose played in the ‘good old days’, when football was somehow better, purer, untarnished.

Rose epitomised all that was good about the era he played in; and he survived and triumphed over its pitfalls – everything from bog-muddy grounds and generally antediluvian player conditions through to a species of on-field violence now unheard of. The most appalling family tragedy simply brought out another level of his extraordinary personal, as distinct from well-known physical, gifts and capacities.

Strevens tells all this in an unadorned, unpretentious and utterly dinkum narrative that is exactly suited to the task and the subject. If it has its hagiographic moments, well, Rose deserved them.

Hagiography is not a temptation Linnell has to deal with in his anatomy of Ablett, whose manifest flaws can neither be ignored nor diminished in importance. The aim of Playing God is to examine ‘Ablett’s experiences with fame and Australia’s obsession with sport’. Denied any cooperation from Ablett himself, Linnell embarks on a process of edging ever closer to him through, in particular, a massive round of interviews with people who might know, or might have known, the man, his world, his background, anything. ‘You’re going to hear a lot of stories about me,’ Ablett tells Linnell with ‘a rare smile’. And he does.

Ablett’s pain, his lack of self-esteem, his fatal indecision based on an inability to trust anyone, his capacity for inexplicable, blind rage, his sense of an emptiness in his life, all emerge as layer after layer of his story is peeled away. The narrative method is a sort of all-out attack: marvellous pen portraits of everyone closely or even temporarily involved (Bill McMaster, Tom Hafey, Malcolm Blight, Rob Astbury, among others); sharp, illuminating analyses of the phenomenon of the fall from fame through enforced, peremptory retirement (Paul Couch, Dwayne Russell, Billy Brownless); lateral allusiveness (Marilyn Monroe and Port Melbourne star Fred Cook, among others); team ‘cultures’ (St Kilda, Hawthorn), and so on. All this is done in a hard, lucid, often effortlessly vernacular prose whose only flaw is that it sometimes seems to be drifting tonally in the direction of Damon Runyon.

Ablett’s is a terrible story, but it is not the only dark note in Playing God, even if it is the most resonant. Just as Strevens refuses to romanticise the now legendary past in which Bob Rose had his hour, so Linnell is, by fairly clear implication at least, unimpressed with the corporate culture of modern football, the sometimes predatory behaviour of the media and the clubs’ ambiguous capacity for on the one hand callousness and on the other a dangerous, reality denying protectiveness.

When Ablett turned up at Geelong to begin his league career, he was by temperament and upbringing incapable of coping with the maelstrom into which his freakish abilities would propel him. Most of what happened thereafter was his own fault, but it was not Ablett who called himself God – on the contrary. ‘Because someone plays football it doesn’t make them God,’ said Alan Horan whose daughter, Alisha, died on a drug and alcohol bender with Ablett.

Linnell wants to know ‘whether football, with its pampering of stars and willingness to cover up and hide their flaws during their careers [should bear] at least some of the responsibility’. The question, like a footballer taking a screamer, hangs in the air.

Comments powered by CComment